Since the 1990s, when the Federal Reserve cuts interest rates, government bond yields also tend to decline, but now there is a clear divergence.

One thing is very clear:

The bond market does not agree with President Trump's view that faster interest rate cuts will lead to a decline in U.S. Treasury yields, thereby lowering mortgage, credit card, and other types of loan rates. As Trump will soon be able to replace Federal Reserve Chairman Powell with his own nominee, another risk is that the Federal Reserve may yield to political pressure and adopt a more aggressive monetary easing, which could damage its credibility—this could backfire, pushing already high inflation even higher and further raising U.S. Treasury yields.

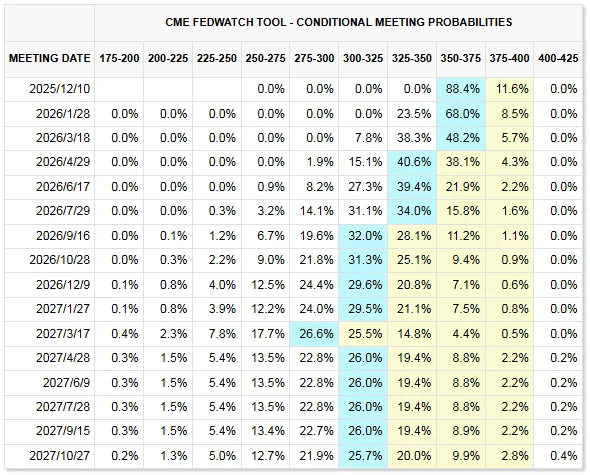

Since September 2024, the Federal Reserve has begun lowering the federal funds rate from its highest level in over twenty years, having cut rates by a cumulative 150 basis points to a range of 3.75%-4%. Traders have fully priced in that the Federal Reserve will cut rates by another 25 basis points this Wednesday and widely expect two more cuts of 25 basis points each next year, bringing the benchmark rate down to 3.00%-3.25%.

However, the key U.S. Treasury yield, which serves as a benchmark for borrowing costs for American consumers and businesses, has not decreased at all. Since the Federal Reserve began easing monetary policy, the 10-year U.S. Treasury yield has risen nearly half a percentage point to 4.1%, while the 30-year U.S. Treasury yield has increased by over 0.8 percentage points.

Typically, when the Federal Reserve raises or lowers short-term policy rates, long-term bond yields tend to move accordingly. Even during the only two non-recession rate-cutting periods in the past forty years (1995 and 1998, when the Fed cut rates by 75 basis points each time), the 10-year U.S. Treasury yield either fell or its increase was much smaller than in this rate-cutting cycle.

Jay Barry, Head of Global Rates Strategy at JPMorgan, identified two main factors behind this. First, during the inflation surge post-pandemic, the Federal Reserve raised rates so significantly that the market had already priced in expectations of easing before the Fed actually pivoted. The 10-year U.S. Treasury yield peaked by the end of 2023. This weakened the impact following this rate cut. Furthermore, the Federal Reserve's decision to significantly cut rates while inflation remains elevated has effectively reduced recession risk, thereby limiting the downside potential for U.S. Treasury yields. Barry stated, “The Federal Reserve aims to sustain this economic expansion rather than end it. That is why U.S. Treasury yields have not fallen significantly.”

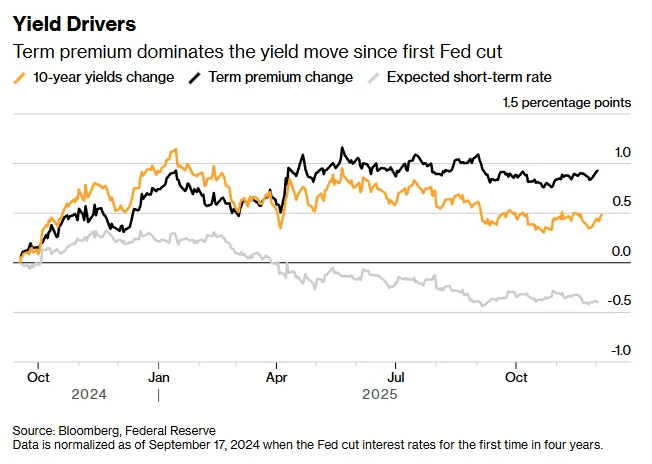

Some people see a more pessimistic explanation from the so-called term premium—namely, the extra compensation investors require for holding long-term bonds to correspond with potential future risks (such as high inflation or unsustainable fiscal deficits). According to estimates from the New York Fed, the term premium has risen by nearly a full percentage point since the start of the rate-cutting cycle.

Since the Federal Reserve's first rate cut this week, term premium has dominated yield changes.

Since the Federal Reserve's first rate cut this week, term premium has dominated yield changes.

Jim Bianco, President of Bianco Research, believes this is a signal indicating that bond traders are concerned about the Federal Reserve continuing to cut rates while inflation remains stubbornly above the 2% target and the economy continues to ignore recession expectations. He stated, “The market is indeed worried about policy, fearing that the Federal Reserve has gone too far.” He added that if the Federal Reserve continues to cut rates, mortgage rates will “rise vertically.”

Additionally, the market is concerned that Trump (who is distinctly different from his predecessor in respecting the Federal Reserve's independence) will successfully pressure policymakers to continue cutting rates. Kevin Hassett, the Director of the White House National Economic Council and a loyal supporter of Trump, is currently the most likely candidate to succeed Powell after his term ends in May.

Markets Live strategist Ed Harrison stated, “If a rate cut increases the likelihood of stronger economic growth, then a rate cut will not lead to lower U.S. Treasury yields, but rather higher U.S. Treasury yields. In many ways, this is because we are returning to a normal interest rate system—2% real return + 2% Federal Reserve inflation target = 4% long-term yield floor. Coupled with stronger growth, that number will only be higher.”

However, so far, the broader bond market has remained relatively stable. The 10-year U.S. Treasury yield has hovered around 4% for the past few months. The breakeven inflation rate— a key gauge of inflation expectations in the bond market—has also remained stable, suggesting that market fears of the Federal Reserve potentially triggering a surge in inflation in the future may be overstated.

Robert Tipp, Chief Investment Strategist for Fixed Income at global insurance asset management giant PGIM, stated that this looks more like a movement back to pre-global financial crisis normal levels. The financial crisis ushered in an era of persistently low interest rates, which abruptly ended after the pandemic. He remarked, “We are back in a normal interest rate world.”

Standard Bank's Steven Barrow pointed out that the Federal Reserve lacks control over long-term U.S. Treasury yields, which reminds him of a similar predicament faced by the Federal Reserve in the early 2000s (albeit in the opposite direction)—the infamous “Greenspan Conundrum.” At that time, Fed Chairman Alan Greenspan was puzzled as to why long-term yields remained low while he continuously raised short-term policy rates. Greenspan's successor, Ben Bernanke, later attributed this “puzzle” to a large influx of overseas surplus savings into U.S. Treasury bonds.

Barrow stated that this dynamic has now reversed, with major economies borrowing excessively. In other words, the past surplus of savings has transformed into an oversupply of bonds, continuously exerting upward pressure on yields. He stated, “Long-term yields may be in a structurally unable-to-decline state. Ultimately, the Federal Reserve cannot dictate long-term rates.”