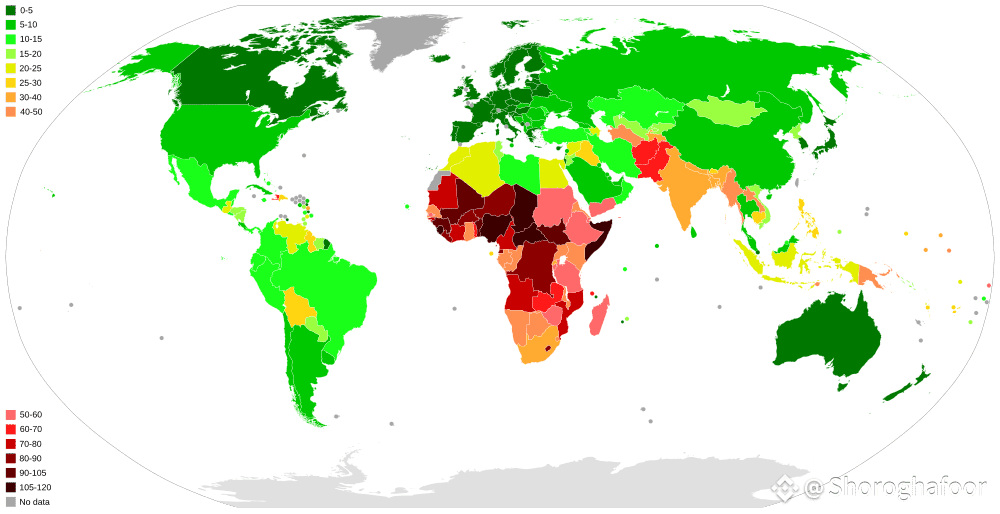

Global and Regional Trends: According to UNICEF and WHO data from 2023, the global IMR was approximately 27 per 1,000 live births, down from 63 in 1990. In developing countries, particularly in Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia, rates are higher. Sub-Saharan Africa had an IMR of about 49 per 1,000 live births, and South Asia around 32 in 2023. For comparison, high-income countries average around 3–5 per 1,000.

Global and Regional Trends: According to UNICEF and WHO data from 2023, the global IMR was approximately 27 per 1,000 live births, down from 63 in 1990. In developing countries, particularly in Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia, rates are higher. Sub-Saharan Africa had an IMR of about 49 per 1,000 live births, and South Asia around 32 in 2023. For comparison, high-income countries average around 3–5 per 1,000.

Key Causes: Major causes of infant mortality in developing countries include:

Neonatal issues (40–60% of deaths): Premature birth, birth asphyxia, neonatal infections, and congenital anomalies. About 75% of neonatal deaths occur in the first week, with 1 million newborns dying within 24 hours.

Post-neonatal deaths: Malnutrition, infectious diseases (pneumonia, diarrhea, malaria), and inadequate healthcare access. Malnutrition alone is a factor in over half of under-five deaths in some regions.

Socioeconomic Factors: Poverty, low maternal education, and lack of access to clean water or sanitation exacerbate risks. For instance, a 10% increase in GDP per capita can reduce IMR by about 5 deaths per 1,000 in developing countries.

Disparities: The risk of infant death in the highest-mortality country (e.g., Afghanistan, estimated at 101.3 per 1,000 in 2024) is about 60–65 times higher than in the lowest-mortality countries (e.g., Japan at 1.9). Sub-Saharan Africa accounts for a disproportionate share of deaths, with a child born there over 10 times more likely to die than one in a high-income country.

Is It a Crisis in 2025?

The term "crisis" depends on context, but several factors highlight ongoing urgency:

Stagnation in Progress: The rate of IMR reduction has slowed since 2015, dropping from 3.7% annually (2000–2015) to 2.2% (2015–2023). This threatens Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) targets to reduce IMR to 12 per 1,000 by 2030. UNICEF estimates 60 countries, many in developing regions, will miss this target without urgent action.

Emerging Threats: Conflicts, economic instability, and fragile health systems are reversing gains in some areas. For example, posts on X highlight acute malnutrition crises in places like Gaza and Sudan, where children face starvation risks, indirectly worsening IMR.

Inequities: Wealth and education disparities mean poorer households face higher IMR. In Sub-Saharan Africa, studies show poorer populations have disproportionately higher mortality rates, with neonatal deaths (first 28 days) being particularly stubborn at 26 per 1,000 in 2023.

Preventable Deaths: Most infant deaths are preventable with low-cost interventions like vaccinations, improved maternal care, and nutrition programs. Yet, 2.3 million newborns died in 2023, many in low-resource settings due to unequal healthcare access.