@Walrus 🦭/acc It’s funny how storage only feels “technical” until the day it stops being there. A video won’t load, a dataset comes back incomplete, a folder opens to an error that feels personal. In decentralized systems that moment arrives more often, because machines come and go. People call it churn, but the human version is simpler: the network is a neighborhood where someone is always moving out.

That’s the backdrop for why Walrus and its “Red Stuff” scheme keeps coming up in 2026. It isn’t just another storage project with a clever codec bolted on. Walrus is trying to be a missing layer that blockchains and decentralized apps keep bumping into: a place for the heavy stuff—media, model files, full frontends, bulky proofs—to live without forcing the chain itself to carry it.

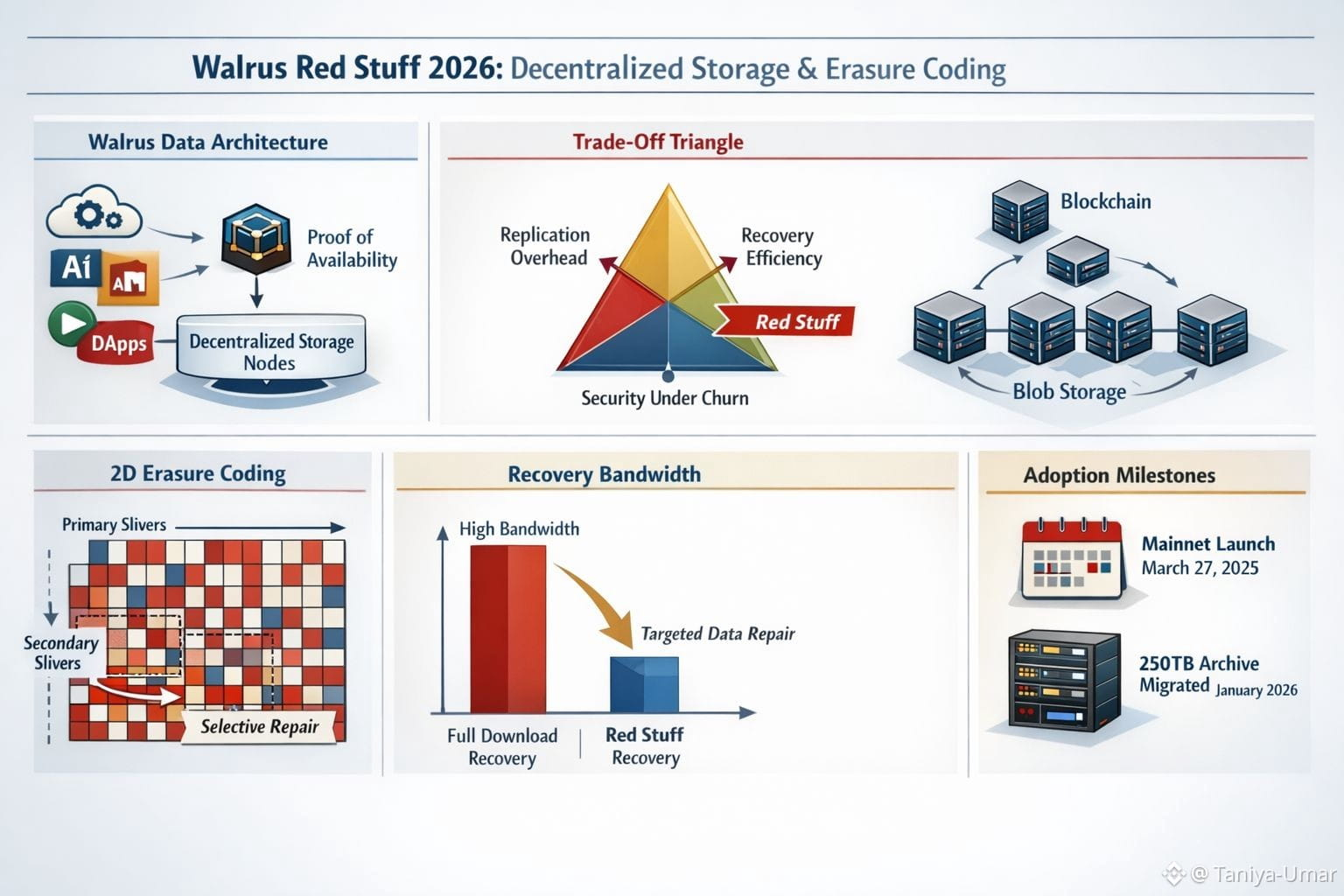

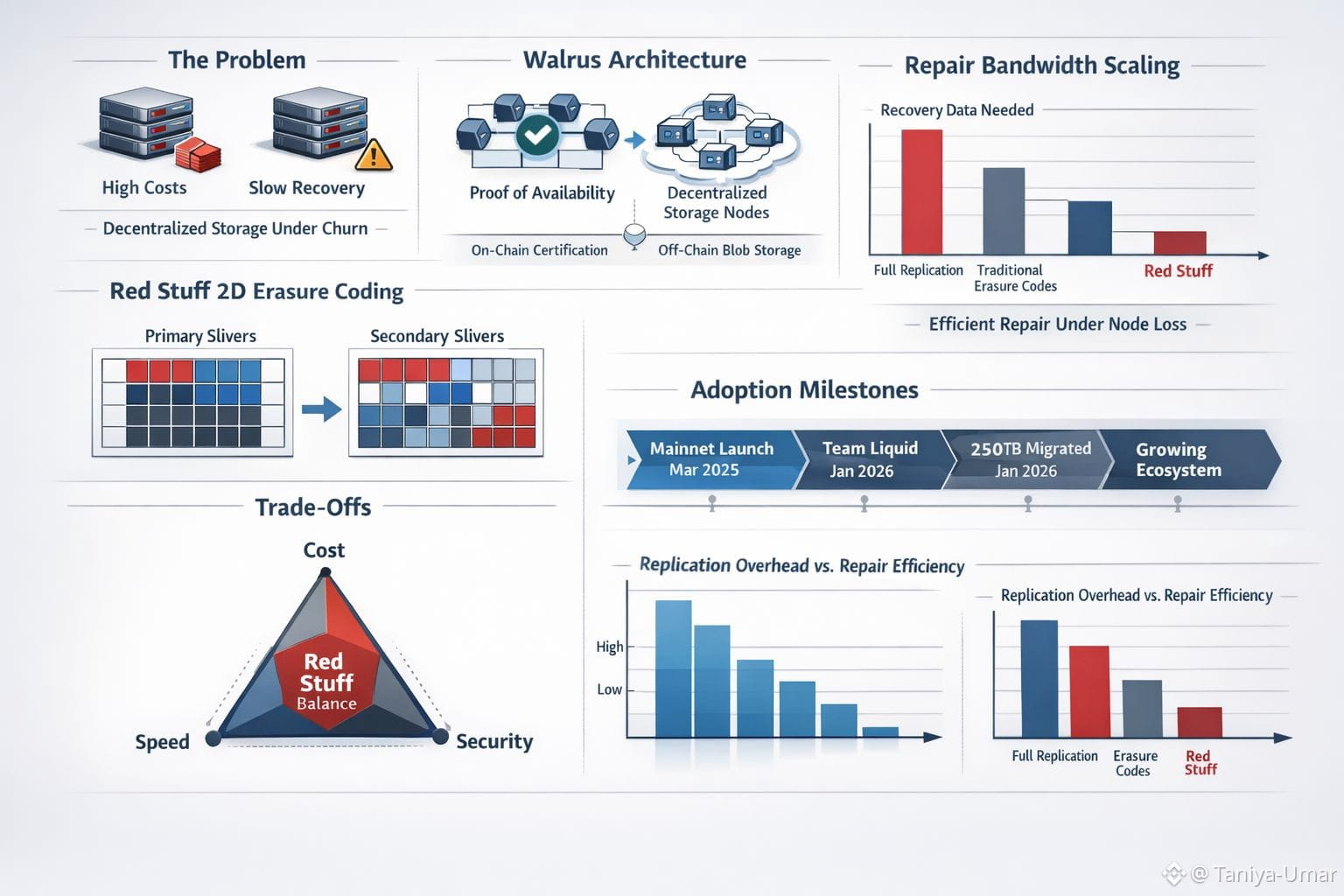

Once you look at it that way, the relevance gets clearer. Chains are great at agreement and ownership, but terrible at being a hard drive. Walrus flips that division of labor into something explicit: store “blobs” off-chain across a decentralized committee of storage nodes, and then anchor proofs of availability on-chain so other people can verify the data is there and should stay there. That last part matters more than it sounds, because “I uploaded it” and “anyone can still retrieve it later” are very different promises in a public network. Walrus calls the on-chain attestation a Proof (or Point) of Availability certificate, and it’s meant to be a durable, verifiable signal that the network has actually taken responsibility for the data.

This is where Red Stuff stops being an interesting math trick and becomes the engine that makes the protocol believable. The Walrus whitepaper frames the core problem as a three-way trade-off: replication overhead, recovery efficiency, and security guarantees, especially under churn. The claim is that many systems pick two and suffer on the third—either full replication that gets expensive, or erasure coding that looks efficient until a node drops and repair traffic explodes. Walrus is explicitly built around that pain point.

Two-dimensional erasure coding sounds fancy, but the picture is plain. Instead of chopping a file into a single line of fragments, Red Stuff lays it out like a grid. Walrus describes creating “primary slivers” and then splitting those into “secondary slivers,” turning one blob into a matrix of pieces. The big practical benefit is repair: when pieces disappear, a node can reconstruct what it’s missing by pulling a smaller, targeted amount from peers, rather than re-downloading something close to the entire blob. The whitepaper makes this point in unusually direct terms, saying recovery bandwidth scales with the lost data instead of the whole file.

If you’ve spent time around classic storage, you’ll recognize the trade-off. Replication is simple and fast to read, but expensive in space. Traditional maximum-efficiency codes save space, but repairs can be rough: one missing fragment can force you to read many others, which is painful when failures are routine rather than rare. That’s why modern storage research keeps circling around “repair” as a first-class design goal, not an afterthought.

Walrus adds another twist that feels very “2026”: it assumes the network is asynchronous and adversarial, not just unreliable. Red Stuff is presented as the first protocol in this design line that supports storage challenges in asynchronous networks, so a malicious node can’t lean on network delays and still pass verification without actually storing the data. If you’re building on a public system where participants have incentives to cheat, that’s not a corner case. It’s the whole point.

And then there’s the cultural reason this is trending now: apps are treating large data as first-class. AI pipelines, verifiable media, onchain games, prediction markets, even “websites” that are meant to be hosted in a decentralized way. Walrus has leaned into that by pitching “programmable storage,” where stored blobs can be represented as objects on-chain so developers can build logic around them, not just point at them. That’s a subtle shift: data stops being a passive attachment and starts behaving like something you can manage, gate, transfer, and verify with the same rigor you apply to onchain assets.

The practical proof points matter. Walrus launched its mainnet on March 27, 2025, and the story since then has been less about concept and more about adoption at uncomfortable sizes. They’ve highlighted Team Liquid moving a massive archive—reported at 250TB—onto the protocol in January 2026. What stands out is the motivation: not novelty, but stability. Reduce single points of failure, make the archive easier to share across time and teams, and avoid another disruptive migration later. That’s the kind of “boring” choice that usually comes from hard-earned experience.

So while Red Stuff gets the attention, the deeper reason Walrus keeps coming up is that it’s trying to make decentralized storage feel dependable. Verifiable availability, repair that doesn’t punish you for normal churn, and an architecture that treats public networks as unpredictable by default—those are not optional details anymore. In 2026, they’re the difference between storage as a demo and storage as something people can build on.

@Walrus 🦭/acc #walrus $WAL #Walrus