@Walrus 🦭/acc A lot of people first hear about Walrus and assume it’s “just storage,” the way a cloud drive is storage. It’s not trying to store tiny records. It’s aiming at the big files people actually struggle to share and keep available—images, video, PDFs, model files, and dataset snapshots. The moment more than one party needs to rely on those files—without handing power to a single company—you start to see why Walrus exists at all.

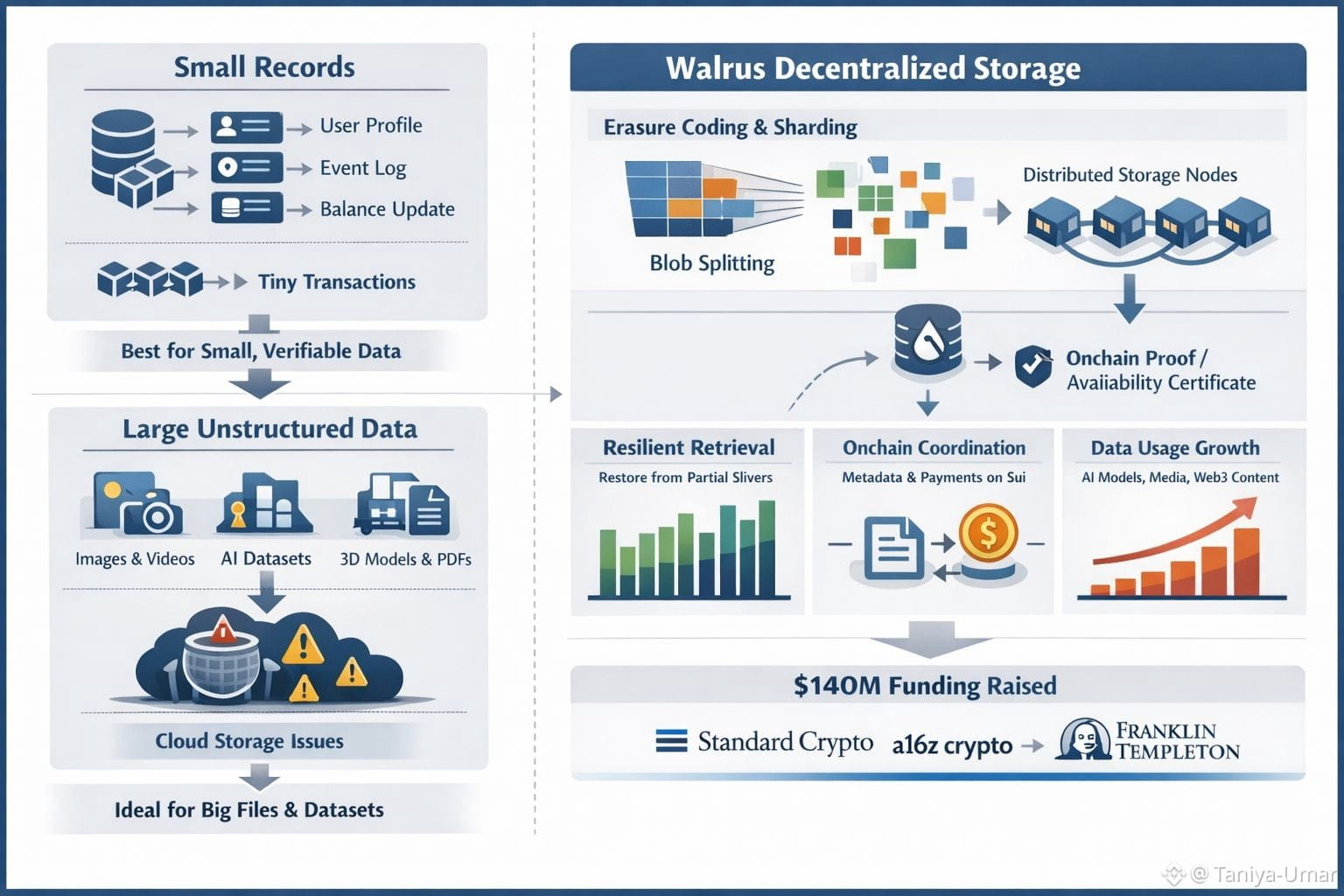

Small records already have decent answers. If you need to update a balance, log an event, or fetch a user profile, databases are great at that. Blockchains are also designed around small, verifiable bits of state: ownership changes, short instructions, and history that many computers can agree on. The trouble begins when “the record” is a 200 MB video or a multi-GB dataset. Storing that directly on a chain is expensive and slow, and it’s usually the wrong tool for the job. On the other hand, putting it in a standard cloud bucket works—until it doesn’t, and you’re suddenly negotiating downtime, pricing changes, access policies, or simple vendor lock-in.

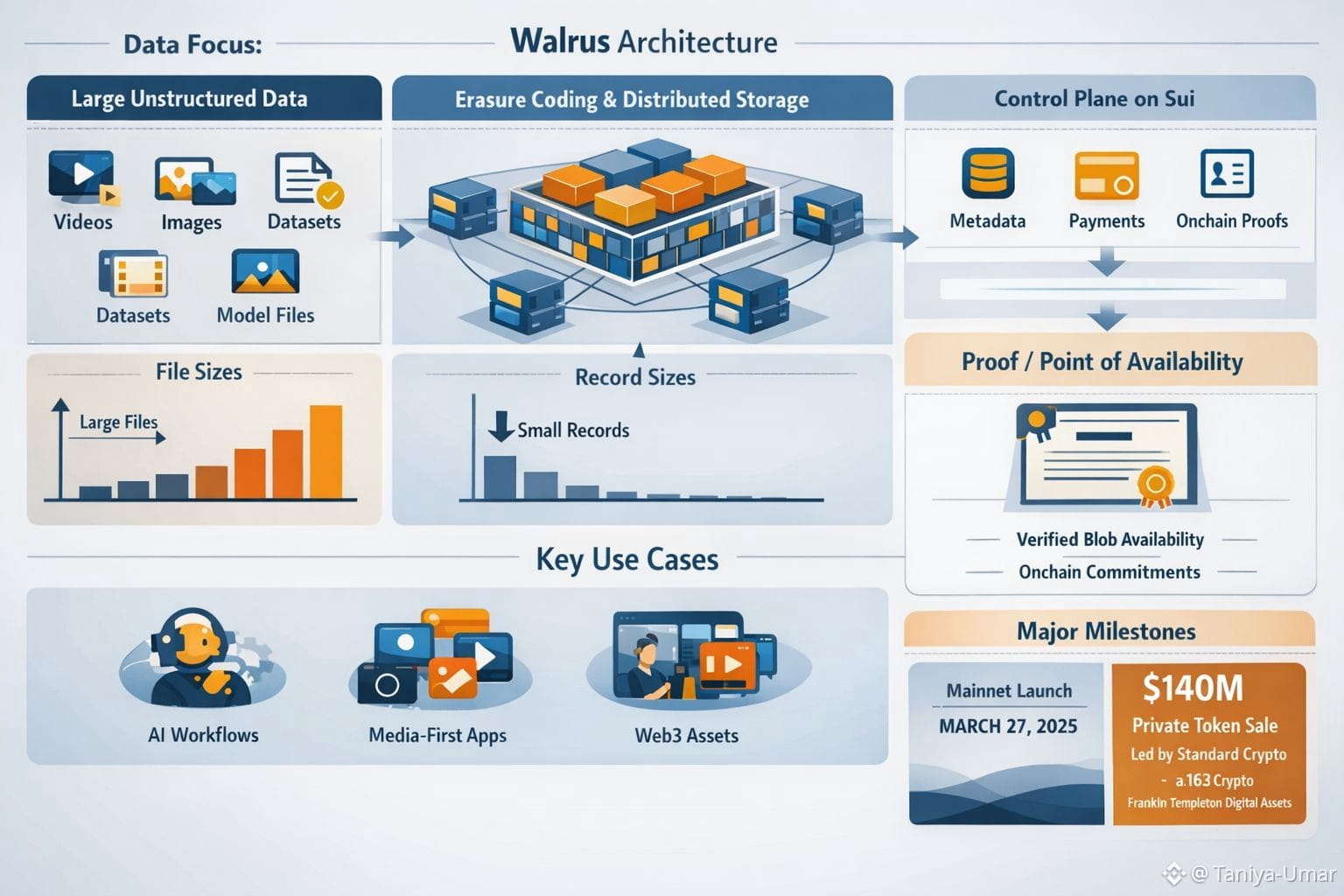

Walrus leans into that gap by treating the large file as the primary unit. Instead of holding your blob in one place, it breaks it into many slivers, adds redundancy, and spreads them across a set of independent storage operators. The engineering detail matters here because it’s not just “copies everywhere.” Walrus uses erasure coding designed so the original file can be rebuilt even if a large portion of the slivers are missing, which is a practical way to handle churn in a decentralized network.

Where it gets especially relevant—right now—is how Walrus ties that storage to verifiable coordination. Walrus uses Sui as a control plane: metadata, payments, and proofs live onchain, while the heavy bytes stay offchain. When a blob is written, the writer collects acknowledgements from storage nodes and publishes a proof-like certificate onchain (Walrus calls this a Proof/Point of Availability). It’s a simple idea with big implications: the network publicly commits that the blob is available for a specified time window, and storage operators are economically bound to keep it retrievable.

This is also why Walrus doesn’t try to compete with small-record databases. In a blob system, the “fixed cost” of coordination—publishing availability, managing incentives, tracking commitments—makes sense when it’s amortized over something large and durable. For tiny records that change constantly, that overhead becomes needless friction. Small records are chatty; blobs are chunky. Walrus is built for the chunky kind.

And that’s where the protocol’s relevance sharpens. The world is producing more unstructured data than ever, and not just as an output of people, but as an output of machines. AI workflows revolve around datasets, checkpoints, embeddings, evaluation artifacts, and model weights—objects that teams want to share, verify, and version without a single point of failure. Meanwhile, consumer apps are increasingly media-first, and web3 apps are increasingly asset-heavy: game content, social posts, NFT media, and “portable” user-generated content that ideally shouldn’t disappear because one host changed its mind.

A big reason Walrus is popping up everywhere is that it stopped being hypothetical. The public mainnet launch on March 27, 2025 was a real milestone—now it’s a decentralized storage network developers can use, not just talk about. And earlier that month, Walrus Foundation announced a $140 million private token sale led by Standard Crypto, with participation from firms including a16z crypto and Franklin Templeton Digital Assets—a signal that serious capital thinks “data plumbing” is now a first-order problem, not a niche.

What I find most convincing is the boundary Walrus draws. Put the truth and commitments onchain. Put the heavy data in a network engineered for availability. That separation feels like an honest answer to a modern reality: the internet runs on blobs, and we’ve outgrown pretending they’re just an afterthought.