Bitcoin’s total supply is capped at 21 million BTC, a hard-coded limit that cannot be changed without

fundamentally altering the protocol. This ceiling is what makes Bitcoin different from fiat currencies or commodities: it is mathematically scarce.

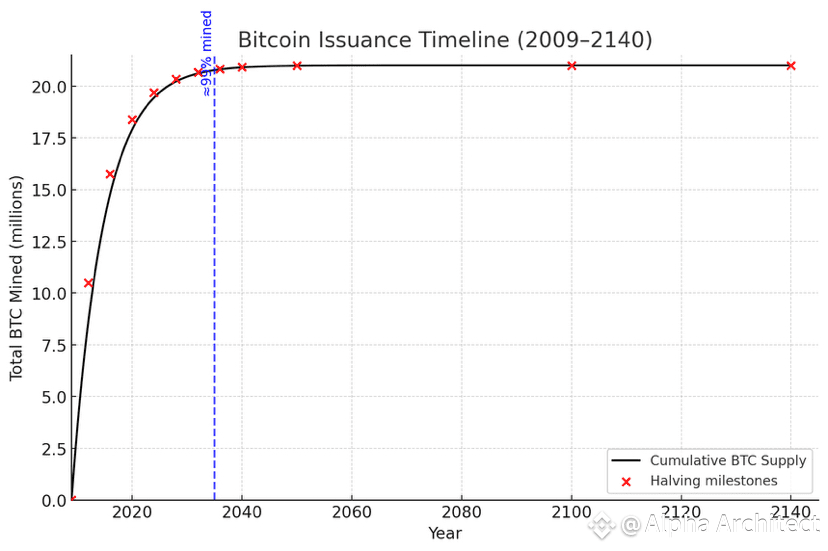

As of May 2025, around 19.6 million BTC (≈93.3% of the total) has already been mined. That leaves only ~1.4 million BTC yet to enter circulation, but these coins will be released at an increasingly slow pace.

The reason lies in Bitcoin’s halving cycle. When the network launched in 2009, miners earned 50 BTC per block. Every 210,000 blocks (roughly every four years), this reward is cut in half. Today, the subsidy is just 3.125 BTC, and it will fall again in 2028 to 1.5625 BTC.

Because of this design, most coins were mined early: by the end of 2020, more than 87% were already in circulation. Going forward, issuance slows so sharply that while 99% will be mined by 2035, the final satoshis will trickle out until around 2140.

This supply curve is asymptotic — rewards never hit zero, but approach it indefinitely. Mining doesn’t stop abruptly; it simply becomes increasingly reliant on transaction fees to sustain security.

Why the True Supply Is Even Smaller

While the 21 million cap is absolute, not all those coins are actually usable. A large fraction is permanently lost — trapped in forgotten wallets, destroyed hard drives, or locked behind lost keys. Analysts estimate 3.0 to 3.8 million BTC (14–18% of supply) is gone forever. That includes the 1.1 million BTC mined by Satoshi Nakamoto, untouched since Bitcoin’s creation.

This means the real circulating supply may be closer to 16–17 million BTC, shrinking Bitcoin’s effective float far below its theoretical maximum. Unlike gold, which can be recycled, lost Bitcoin is irretrievable — supply only hardens over time.

What Happens After the Last Bitcoin?

A common misconception is that Bitcoin’s security will collapse once mining rewards dwindle. In practice, the system is designed to adapt.

Mining economics are governed by a feedback loop. If rewards plus fees can’t cover costs, miners shut down machines. This reduces hashrate, which triggers a difficulty adjustment every 2,016 blocks, restoring profitability for those who remain.

This resilience was demonstrated in 2021, when China banned mining and global hashrate fell more than 50% in weeks. Yet the network never missed a beat, and hashrate later recovered as miners relocated.

Even in the distant future, when rewards are negligible, miners will still compete for transaction fees.

Already, fees occasionally surpass block subsidies: on April 20, 2024, thanks to the launch of the Runes protocol, miners earned $80 million in fees in a single day, triple the block reward.

Thus, Bitcoin’s long-term security doesn’t depend on rewards staying high — it depends on fees and incentives continuing to balance costs.

Mining and Energy Use

Bitcoin is often criticized for high energy consumption. But the economics of mining limit expansion.

Higher prices attract miners, which raises difficulty, compressing margins and capping energy growth.

Today, efficiency is pushing miners toward cheap, stranded, or renewable energy. Following China’s exit, hashrate migrated to North America and Europe, where operators tap into hydro, wind, and underutilized grids.

The Cambridge Centre for Alternative Finance estimates that 52–59% of Bitcoin mining now uses renewable or low-emission energy sources. In some regions, regulations and incentives are accelerating this shift.

The dystopian image of endlessly growing, fossil-fueled mining is increasingly outdated. Bitcoin mining is evolving into a demand-balancing force, absorbing surplus energy and incentivizing cleaner grids.

The Future of Bitcoin Scarcity

Bitcoin is entering its monetary “gold phase”: slow issuance, concentration of holdings, and heightened sensitivity to demand. Yet it goes further than gold: - Its cap is absolute, not flexible. - Lost coins make supply smaller over time. - Distribution is transparent and auditable.

This engineered scarcity could lead to: - Increased price volatility as circulating supply tightens. -

Growing importance of liquidity, with spendable BTC trading at a premium to dormant supply. - Wealth concentration among those who manage their keys securely for decades.

By 2140, the last satoshis will be mined — but Bitcoin’s scarcity will already have reshaped its role in the global economy long before then.