If the cryptocurrency world is never short of dramatic stories, this time, the protagonist has changed to Monero.

This was not a sudden attack but a power struggle that had been announced a month in advance—a prepared confrontation—the attackers even announced they 'would challenge the Monero network from August 2 to August 31'. Their target was aimed at a rare achievement in the blockchain world: controlling 51% of the computational power of a privacy coin network valued at over $5 billion.

And today, the attackers claim they have achieved this goal.

This is a long-planned attack.

We all know that in a blockchain network, all transactions must be verified by miners, a process known as 'mining'. The computational power of miners is called computational power; the higher the computational power, the greater the chance of mining new blocks and receiving rewards.

The same goes for Monero.

However, compared to other coins, Monero has a design to prevent large mining pools from committing wrongdoing—ASIC (Application-Specific Integrated Circuit) miners are not supported, and only ordinary computer CPUs or GPUs can mine. The intention behind this rule is to prevent miners from gathering in one large mining pool, making it theoretically possible for anyone to participate in mining with their own computers, thus making the network fairer and more decentralized.

However, this mechanism also has an idealized attack method, which is to rent or mobilize a large number of ordinary servers (such as cloud computing resources, idle PCs, miners' computers) in a short time. And this is precisely the method used by the attackers.

Now let's look at this premeditated attacker called Qubic.

The initiator of this action is Qubic, an independent blockchain project not created specifically to attack Monero. It is led by IOTA co-founder and senior crypto developer Sergey Ivancheglo (nickname Come-From-Beyond), using a 'Useful Proof of Work' (UPoW) mechanism that allows miners' computational power to not only solve mathematical problems but also train its AI system 'Aigarth', achieving two goals at once.

So why did it associate with Monero and launch a computational power 'war' against it?

In fact, this is an 'economic demonstration' of Qubic showcasing its UPoW model capabilities. Starting in May 2025, it successfully attracted a large number of miners to join by using its network's computational power for CPU mining of Monero, simultaneously earning both Monero and $QUBIC token rewards from mining. The Monero mined by miners would be sold for stablecoins to repurchase and destroy Qubic coins, forming a self-reinforcing economic cycle.

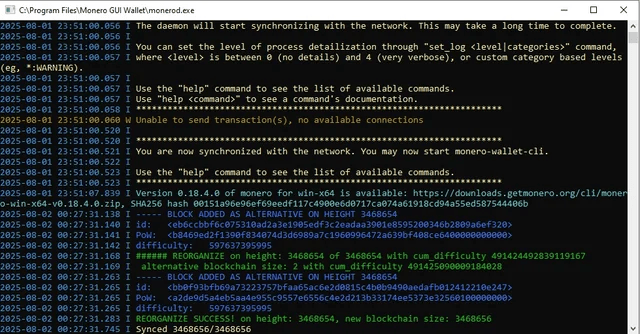

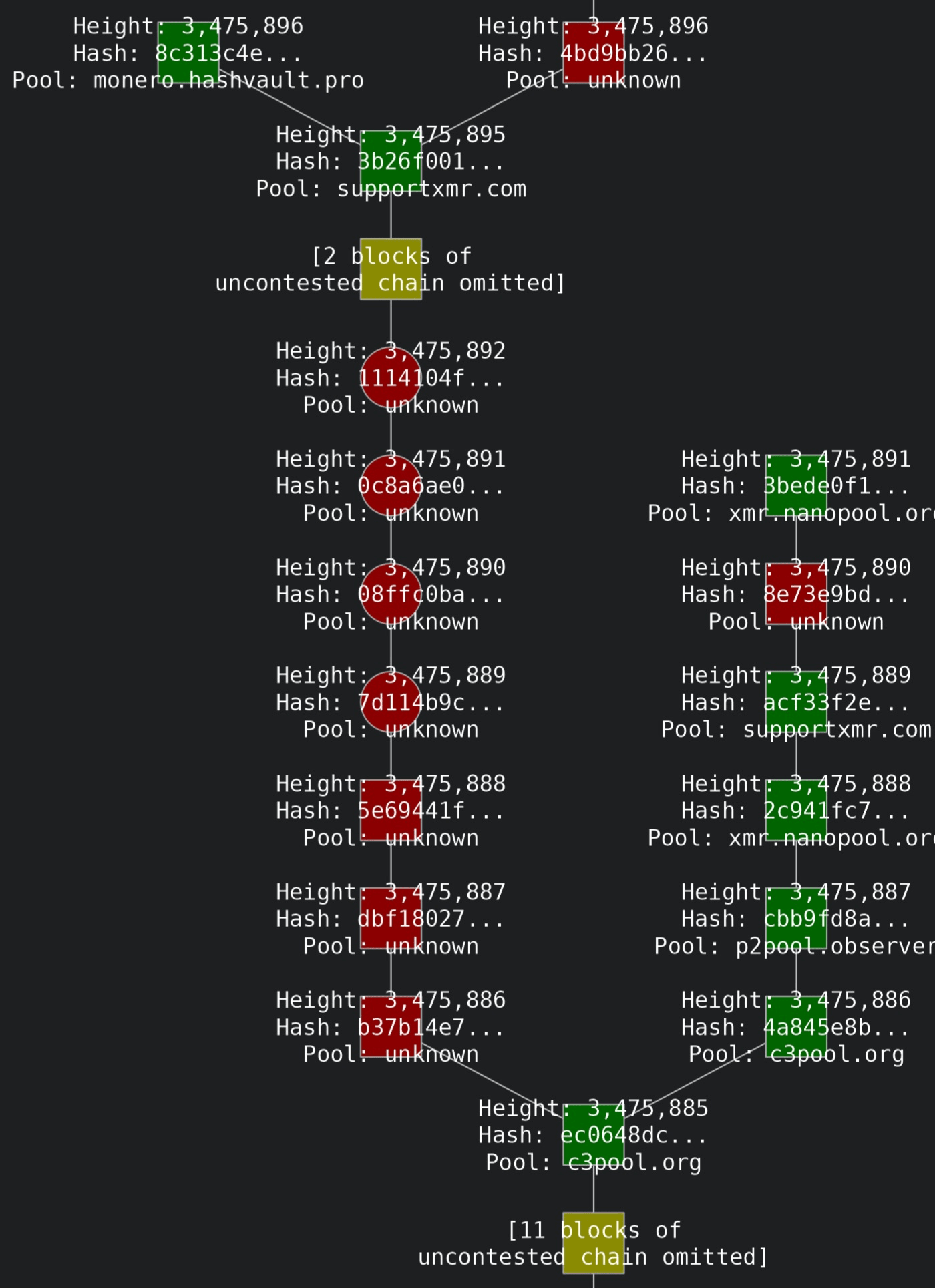

After Qubic announced it would 'challenge' the Monero network from August 2 to August 31, some Monero community members began to monitor the situation on the chain around the clock. Someone on Reddit stated that they would keep an eye on every block, especially paying attention to the occurrence of 'orphan blocks'. Initially, everything was normal, but one night they noticed a chain reorganization. In theory, chain reorganization is not uncommon in the Monero network; for example, when two miners simultaneously mine a block, the system will choose one and discard the other. However, the timing of this reorganization was suspicious, seemingly related to Qubic testing its ability to insert alternative blocks and fork the blockchain. Although that alternative block was ultimately rejected, it indicated that Qubic was attempting to take action.

The status of Monero's blocks.

Observers also noted that Monero was supposed to generate a block every two minutes, but the block generation speed has recently noticeably accelerated, and the network seems to have detected signs of potential attack pressure. This convinced him that Qubic was indeed performing some kind of interference. Another participant pointed out that the only orphan block that occurred was 12 hours before Qubic publicly claimed it would launch an attack.

On the computational power data, the community also observed that Qubic stopped reporting its computational power to public mining pool statistics websites at the beginning of August, which made it impossible for outsiders to see their actual mining capabilities directly. Some speculate that this may be to hide peak computational power, create opacity, and show more favorable numbers through their own controlled website.

The result of Qubic's premeditated attack to 'show muscle' was that during July, Qubic accounted for nearly 40% of the Monero network's computational power. By August, Qubic claimed to have reached 52.72%, directly crossing the 51% 'control threshold'—this means it technically has the ability to reorganize the chain, conduct double-spending attacks, or censor transactions. Qubic claimed this was to simulate potential attacks on the Monero network and to discover security weaknesses early.

In fact, is Qubic just bluffing?

So did Qubic really successfully conduct a 51% attack? Many people remain skeptical about this, believing it is merely a deliberately deceptive marketing move.

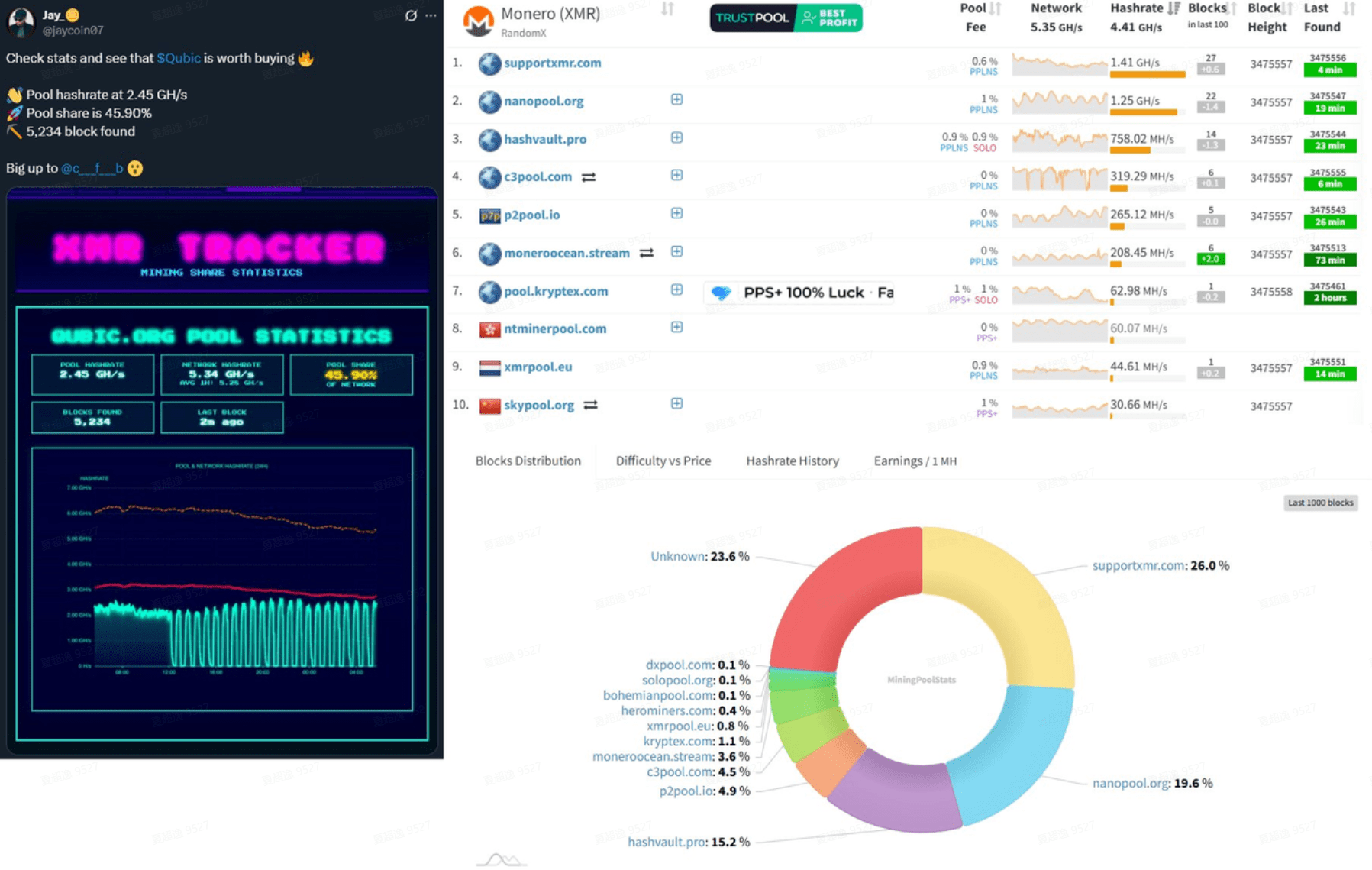

@VictorMoneroXMR raised doubts with the screenshot below. When the total computational power of other Monero mining pools showed 4.41 GH/s and the total network power showed 5.35 GH/s, Qubic's dashboard displayed that it had 2.45 GH/s of computational power under the same total network power, which clearly does not match, and it is possible that Qubic's dashboard did not include its own computational power in the total network power. If we adjust based on this assumption, Qubic's computational power actually accounts for only about 30% of the total.

Besides data doubts, the most direct on-chain evidence so far is that Monero has experienced a continuous six-block reorganization, but this does not 100% confirm that Qubic has the ability to launch a 51% attack.

This point is also supported in real-time monitoring posts about blocks in the Monero Reddit community.

During the entire Qubic challenge period, the community did not see a sustained and significant increase in orphan blocks or chain reorganizations, only one suspected reorg, and the alternative block was rejected. Core developers and the community observed that Qubic had approached or even slightly exceeded 50% computational power during certain periods (Qubic claimed to have reached 52.72%); even if it briefly exceeded 51%, if only for a few minutes or a few blocks, it may not be able to conduct an effective attack.

This means that there is currently no evidence showing they have consistently maintained above 51% long enough to launch a successful attack.

Currently, the consensus within the Monero community is that Qubic may have briefly exceeded 51%, but did not execute an effective attack; it seems more like a display of computational power and psychological warfare. The attackers might be displaying exaggerated percentage screenshots on their website, creating the impression that they have taken control of the network.

Spending $75 million to earn $100,000 in a losing deal?

The attack cost of Qubic has also sparked a lot of discussions on social platforms.

The analysis within the Monero community generally believes that maintaining the current computational power controlled by Qubic is extremely costly. Based on the current network difficulty, the daily block rewards for the entire Monero network are valued at about $150,000. If attackers want to maintain over 50% of the total network computational power, it means they need to produce blocks equivalent to half or more of the total network daily, and the costs for hardware, electricity, and operations are staggering.

According to calculations by the founder of security company SlowMist, the cost of such a large-scale attack could reach $75 million per day, a figure that is nearly impossible to recoup purely through speculative mining.

Due to this astronomical figure, let's analyze from other perspectives. First, look at Crypto51, a website specifically used to estimate the cost of 51% attacks on different PoW coins. For some mainstream or small to medium market cap coins, it provides hourly rental cost references, for example: Ethereum Classic (market cap of about several hundred million dollars): about $11,563 per hour; Litecoin: about $131,413 per hour.

Although Crypto51 does not have specific data for Monero, it can be seen that even for medium-sized PoW networks, the attack cost is usually far below the level of tens of millions of dollars per day.

Based on discussions on Reddit, a community friend attempted to estimate the attack cost for CPU PoW (such as Monero): assuming the use of AMD Threadripper 3990X (performance of about 64 KH/s), about 44,302 of such CPUs would be needed to achieve 51% of the total network. The equipment purchase cost alone would be around $220 million (44,302 × $5,000). If other hardware costs, site rental, and electricity expenses are included, an additional tens of millions of dollars would be needed. The electricity cost is expected to be about $100,000 per day.

So how much profit can Qubic make from a $75 million per day attack cost?

According to Monero's current tail emission rules, the block time is about 2 minutes, and the reward for each block is fixed at 0.6 XMR. If Qubic controls over 51% of the computational power, it means they have the ability to mine all of Monero's blocks in a day, which is about 432 XMR.

When we wrote this article, the price of Monero was about $246. Based on the current price of Monero, if Qubic monopolized all Monero output in one day, it could only profit about $106,000.

According to Qubic's official 'Epoch 172 Report', Qubic distributes the Monero it mines at a 50% - 50% ratio, meaning half is used to repurchase and destroy $QUBIC, while the other half is used for miner incentives. However, miners' rewards are still paid in $QUBIC.

In other words, with a market cap of less than $300 million for $QUBIC, it has the ability to monopolize the output of Monero, which has a market cap of nearly $4.6 billion. Theoretically, they could go all out and destroy $53,000 worth of $QUBIC in a day, and $1.509 million worth of $QUBIC in a month, which is simply insane.

Monero's counterattack, an ongoing battle.

Therefore, outsiders generally believe that Qubic's motivation is not just to directly mine Monero for profit, but to support a 'computational power + token' economic model: Qubic does not directly pay miners with fiat currency but rewards them with its own token $QUBIC, while artificially maintaining the secondary market price of the token—once the price stabilizes or even rises, they can exchange a relatively low token issuance cost for a large amount of real computational power support. The core of this practice is that the rewards miners earn from mining Monero in the Qubic pool will be exchanged for Qubic tokens. If the token price remains high, the nominal earnings for miners will be considerable, naturally attracting them.

In terms of profit models, Qubic itself does not necessarily rely on Monero's block rewards to make money, but instead leverages this event to create hype for its tokens, increasing trading volume and prices, thus bringing more speculative buying.

As long as the market cap and liquidity of Qubic coins are maintained at a level sufficient to pay miners, this large-scale computational power occupation can continue. However, this model is built on a highly fragile foundation of confidence: if miners feel that Qubic's token price is difficult to maintain, they will collectively sell off to return to more stable assets, triggering a price collapse and causing a 'race to the exit'.

This is a blatant and domineering 'siphoning' of computational power, which naturally aroused strong dissatisfaction and counterattacks from the Monero community.

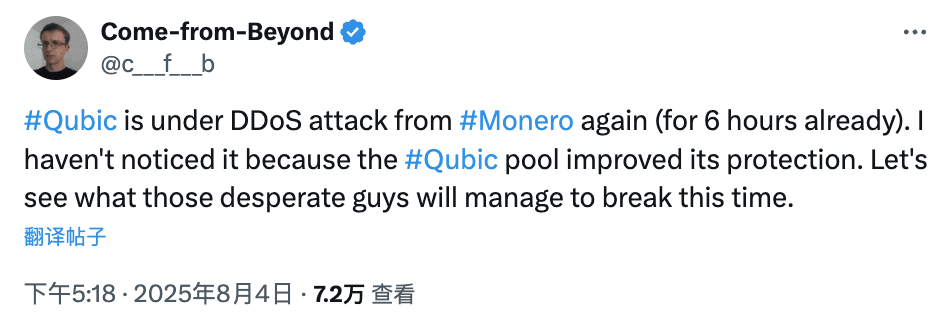

Interestingly, during Qubic's attack on Monero, it also suffered anonymous attacks.

According to Qubic founder Sergey Ivancheglo (nickname Come-From-Beyond), their mining pool encountered a DDoS attack (Distributed Denial of Service attack) during this phase. Qubic reported that its mining pool's computational power dropped from about 2.6 GH/s to 0.8 GH/s, a decline of over 70%. Therefore, he believes that someone deliberately interfered with their computational power operations through cyber attacks.

The attacker, Qubic founder Sergey Ivancheglo, stated that he was also attacked.

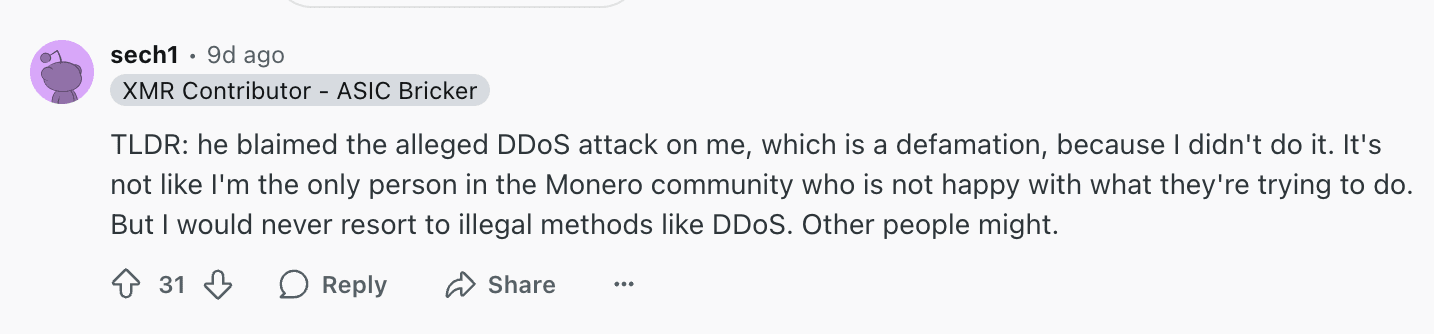

During the accusations, Ivancheglo even named and suspected the main developer of Monero mining software XMRig, Sergei Chernykh (nickname sech1), as the mastermind. However, sech1 immediately responded, clearly denying any involvement in illegal attacks: 'I am not the only one in the Monero community dissatisfied with Qubic's actions. But I would never resort to illegal means like DDoS. Others might.'

The main developer of Monero mining software XMRig stated, 'I am not the only one in the Monero community dissatisfied with Qubic's actions.'

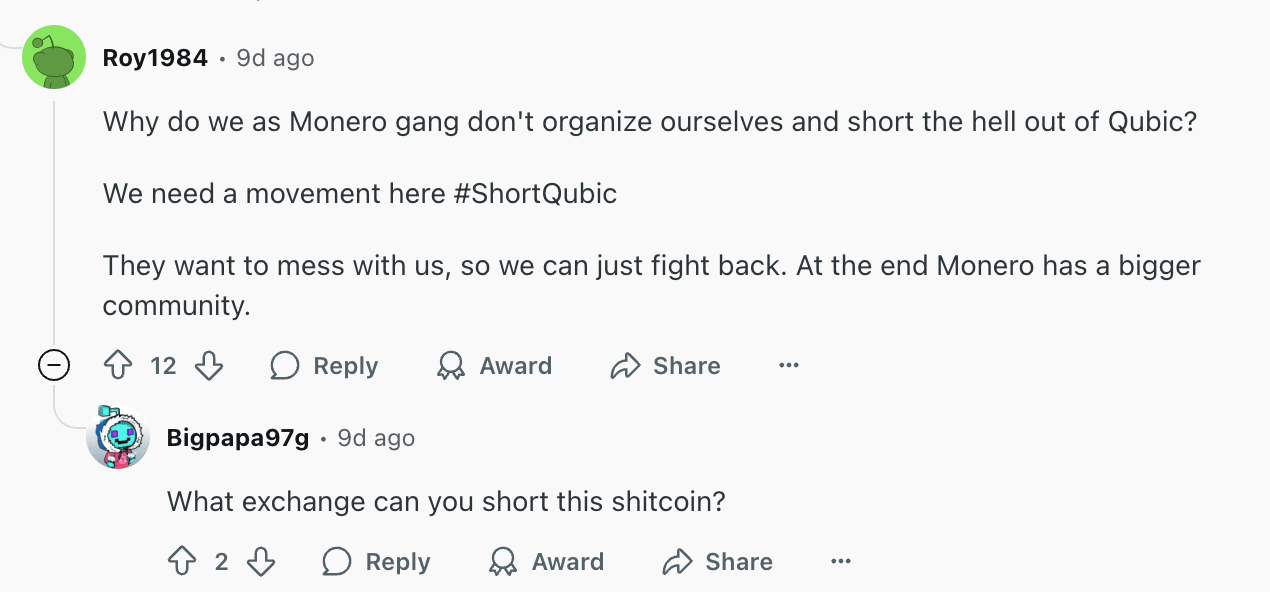

At the same time, it seems that the Monero community is also discussing that all Monero supporters should organize and completely eliminate Qubic.

'We need a movement #ShortQubic, they want to provoke us, we can only counterattack. After all, the Monero community is larger.' 'Where to short Qubic? Why don't we collectively short Qubic Coin or even leverage it? That would completely stifle miners' enthusiasm.'

The Monero community discusses how to counterattack.

Interestingly, some members of the Monero community pointed out that Qubic's attack on Monero might also have ideological reasons.

Qubic's official website shows that the team has many members, but most use pseudonyms; only two use real names, one of whom is the previously mentioned Qubic founder Sergey Ivancheglo, and the other is Qubic scientist David Vivancos, who advocates for the combination of human and machine. David Vivancos is described as a 'technocrat', who believes in a model of social management driven by technology experts and data. This philosophy has been criticized as contrary to Monero's pursuit of decentralization, privacy, and community autonomy, and even carries a dystopian flavor.

This attack and defense have not ended; the smoke of psychological warfare is still lingering. Will the Monero community counter Qubic through technology, finance, or public opinion? And how long can Qubic's 'computational power siphoning' last? Rhythm BlockBeats will continue to pay attention.