Written by: Saurabh Deshpande, Decentralised.co

Compiled by: AididiaoJP, Foresight News

In November 2023, Blackstone acquired a pet care app called Rover. Rover initially served just to find dog walkers or cat sitters. The pet care industry typically comprises thousands of small, often localized, offline service providers. Rover integrated these suppliers into a searchable marketplace, adding ratings and payment features, making it the default platform for pet care services. By the time Blackstone privatized it in 2024, Rover had become the hub of demand in that field. Pet owners first think of Rover, and service providers have no choice but to list on this platform.

ZipRecruiter did something similar in the recruitment space. It collected job information from employers, job sites, and applicant tracking systems and distributed it across multiple channels. ZipRecruiter posts job listings on social networks like Facebook. For employers, ZipRecruiter becomes a one-stop distribution channel; for job seekers, it is a unified entry point to the market. ZipRecruiter does not own companies or positions but owns relationships with both parties. Once this relationship is solidified, it can charge for visibility and job matching, which is an introductory lesson in aggregation economics.

Aswath Damodaran describes this model as 'controlling the shelf': concentrating chaotic, dispersed supply, controlling how it is displayed, and charging for access. Ben Thompson calls it 'aggregation theory': establishing direct relationships with end-users, allowing suppliers to compete to serve them, and extracting value from each transaction. The core characteristics across different domains are consistent: Google with web pages, Airbnb with listings, Amazon with products.

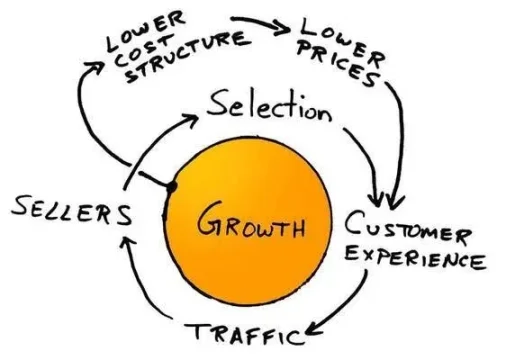

The Amazon flywheel is a classic illustration of this concept. During the downturn after the dot-com bubble burst, Jeff Bezos and his team borrowed from Jim Collins' 'flywheel' concept to sketch a loop that every MBA can now recite: more choices lead to better customer experiences, attracting more traffic, which in turn attracts more sellers, lowering unit cost structures and enabling lower prices, ultimately leading to more choices. A single rotation of the flywheel has limited effect, but after a thousand turns, the machine begins to hum. Bezos' motto during this period was: 'Your profit is my opportunity.' The core lies in self-reinforcement: more users, more suppliers, lower costs, and ultimately higher profits.

Once this model works, it can be perfect. The growth rate of costs is far lower than that of revenues, and products will optimize as user numbers increase. But this only holds under two conditions: the aggregated content must hold value, and suppliers must find it difficult to exit easily; without either, the moat becomes shallow. Take eBay as an example; it aggregated millions of unique niche sellers and buyers in the early 21st century. This aggregation was once highly valuable, but when sellers realized they could establish their own stores on Shopify or migrate to Amazon, they began to leave. The flywheel does not stop overnight, but if suppliers no longer remain in control, it begins to wobble, eventually becoming ordinary.

Damodaran illustrates the power of platforms and aggregators in a tangible way. He mentions 'controlling the shelf,' not in the literal sense of supermarket shelves but as the space first contacted when customer demand arises. Controlling this space means deciding how content is displayed, how it is shown, and the cost of entry. You do not need to own the products themselves; you just need to own relationships with buyers, and others must go through you to reach buyers. In analyzing Instacart, Uber, Airbnb, or Zomato, Damodaran repeatedly emphasizes: the aggregator's task is to consolidate chaotic, dispersed markets into a single display case and make that display the only one worth observing. Once achieved, you can charge for 'viewing rights.'

Ben Thompson argues that aggregators are businesses that establish direct relationships with end-users at internet scale, providing standardized and reliable experiences, and allowing suppliers to compete to serve them. At internet scale, you are not the largest store in town, but a store that covers all towns simultaneously.

The marginal cost of serving the next customer is nearly zero, but the marginal value of owning them is massive. Because each customer reinforces your brand, data, and network effects. Since aggregators control demand, suppliers become interchangeable. This does not mean quality is indistinguishable, but rather that suppliers cannot take customer relationships with them when they leave. Hotels on Expedia, drivers on Uber, sellers on Amazon—they all need each other more than the aggregator does.

Damodaran's research reminds us that flywheels do not operate the same way in all markets. For example, Uber aggregates local driver liquidity, but drivers can open three apps simultaneously and choose the first order received. This creates vulnerabilities in the moat. In contrast, Airbnb hosts offer unique listings with limited alternative channels, making their commissions more sustainable.

In lower-margin areas, shelves may hold value, but there is limited room for commissions, and suppliers can easily rebound. This is why Instacart must venture into advertising and white-label logistics to achieve growth.

The economic structure of supply is as important as the number of users focused on the platform. If the goods within the platform are readily available, you are merely a convenience store with better visibility; but if the content is scarce, differentiated, and hard to replace, people will continue to frequent it even if you charge higher fees. Think of high-end listings on Airbnb.

Why aggregators fail

When conditions are missing, aggregators are no longer a flywheel but merely an expensive carousel.

Quibi is a typical case of failing to control the shelf. The platform had expensive Hollywood content and a polished app but lacked direct channels to users. Potential users had already gathered on YouTube, Instagram, and TikTok. These platforms controlled attention, while Quibi locked content in a standalone app away from users, forcing it to rely on ads and promotions to attract users.

Excellent aggregators start with zero marginal cost user outreach methods, such as built-in distribution, installations, or daily habits. Quibi had nothing and ultimately ran out of time and money before building any of these.

Facebook's Instant Articles faced similar issues. Its idea was to aggregate content from publishers, accelerating loading and monetizing traffic within Facebook. But publishers could easily distribute content to their open networks, apps, or other social platforms. Instant Articles never became the default reading platform, merely an option in the information stream.

Both examples violate the same rule: companies fail to own user relationships in a way that creates default behavior, and the supply side does not suffer significantly after exiting.

The checklist for excellent aggregators is simple:

Directly connect and own user relationships;

Suppliers must be either unique or interchangeable enough that they will not be held hostage by a single supplier;

The marginal costs of increasing supply must be close to zero or low enough to optimize the business model with scale.

If these conditions are not met, you are just another easily replaceable intermediary.

How liquidity becomes a moat

In the crypto industry, projects can build moats in various ways. Some build trust through licenses and regulation (like USDC), some rely on technology (like Starkware's proof systems or Solana's parallel execution), and others depend on community and network effects (like Farcaster's user graph). But the hardest to shake is liquidity.

"Correct execution" is crucial. But if the incentives are strong enough, liquidity can shift rapidly. In 2020, Sushiswap withdrew over $1 billion from Uniswap in just a few days through liquidity mining rewards. The lesson is simple: liquidity only stabilizes when leaving is more painful than staying.

Hyperliquid understands this well. It not only builds the deepest order book for perpetual contract exchanges but also allows other applications and wallets to connect directly to its liquidity. For instance, Phantom can access Hyperliquid's order flow, providing users with narrow spreads without having to build a market themselves. In this model, aggregators need suppliers more than ever. When traders and applications default through your routing, you are no longer an ordinary aggregator but an indispensable core channel.

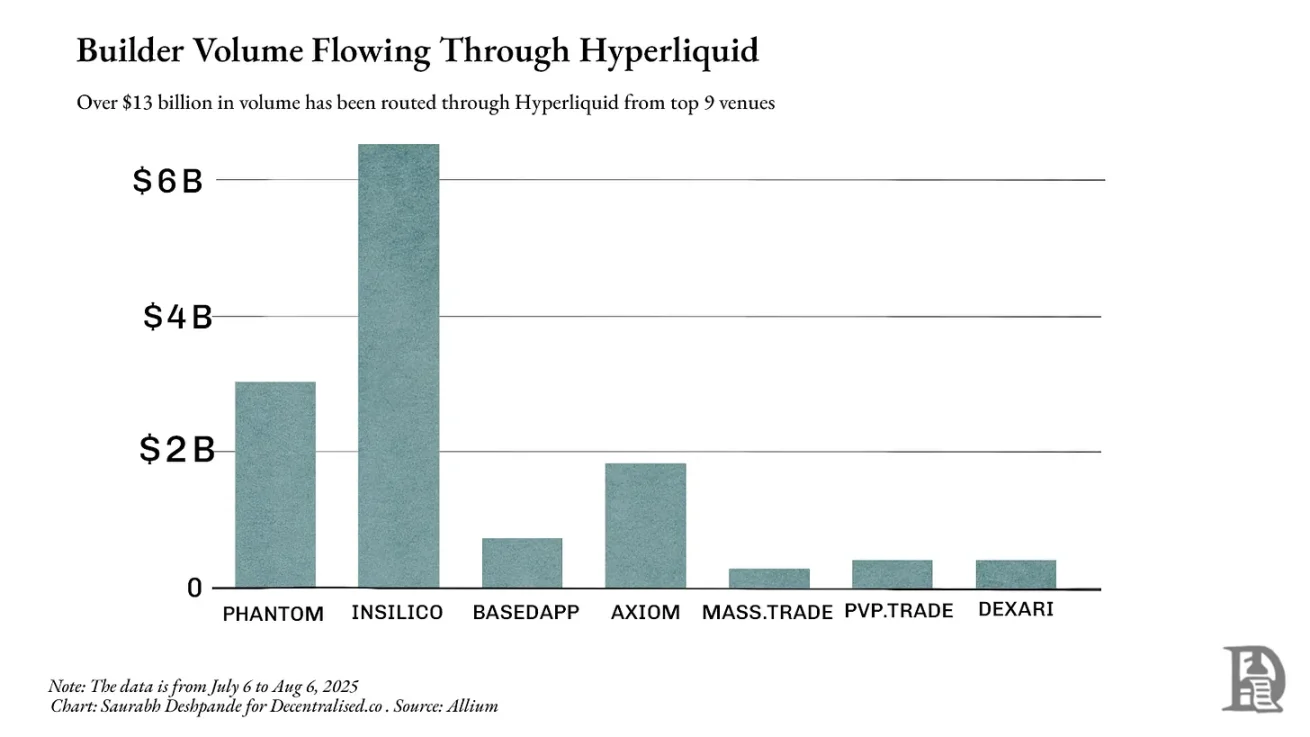

Aside from its own platform, Hyperliquid processed over $13 billion in trading volume last month through other builders. Phantom processed $3 billion in trading volume through its routing, earning over $1.5 million. This showcases Hyperliquid's current strong network effects.

Liquidity allows you to convert assets without affecting prices. In finance and DeFi, deep liquidity makes trading cheaper, borrowing safer, and derivatives possible. A lack of liquidity can turn even the most perfect protocol into a ghost town. Once successfully established, liquidity tends to persist. Traders and applications will flow to deep pools, further increasing liquidity, narrowing spreads, and attracting more trades.

This is the reason protocols like Aave endure. Aave has large-scale lending pools for multiple assets, making it the preferred choice for lenders and borrowers seeking scale and security. As of August 6, Aave's total cross-chain locked value exceeded $24 billion. Over the past 12 months, borrowers have paid $640 million in fees, with platform revenue around $110 million.

The Solana-based aggregator Jupiter has evolved from a routing tool to the default entry point for trading on the network. On Ethereum, Uniswap has centralized most spot liquidity, so aggregators like 1inch can only offer marginal improvements. In Solana, liquidity is dispersed across platforms like Orca, Raydium, and Serum. Jupiter integrates this into a single routing layer, always providing the best price. Its trading volume once accounted for nearly half of Solana's total computational usage, and any delays or interruptions would immediately impact the execution quality across the network.

Viewing liquidity as an object to be aggregated makes Jupiter's product decisions more understandable. Acquisitions, mobile applications, and expansions into new trading and lending products are all aimed at capturing more order flow, keeping liquidity routed through Jupiter, and solidifying its position.

Jupiter deserves attention because it is a clear case of evolving from a niche tool to a liquidity platform in DeFi. It started with finding the best spot prices, gradually becoming the default routing for Solana liquidity, and then expanded to attract new liquidity products. Observing how it navigates these stages and reinforces each other provides a vivid case for the dynamics of aggregation.

The hierarchy of aggregation

Three questions serve as a quick checklist for identifying potential aggregators:

What are the key differentiators of existing enterprises? Can they be digitized? In DeFi, the differentiator is liquidity. Deep pools can provide narrower spreads and safer loans. Liquidity is already digitized, easily readable, and comparable.

If differentiators are digitized, does competition shift to user experience? When liquidity can be accessed at will, competition revolves around execution quality: faster settlements, better routing, fewer failed transactions. Products like BasedApp and Lootbase have emerged as a result. The former encapsulates DeFi primitives into a smooth mobile experience, while the latter brings Hyperliquid's deep perpetual liquidity to mobile.

If you win the user experience, can you build a virtuous cycle? Traders come for better prices, attracting more liquidity, which in turn provides better prices. When liquidity is embedded in habits and integrations, it becomes sticky.

Becoming the default entry point for the market means that if the supply side cannot bear your absence, you can collect display fees or decide the order flow in DeFi.

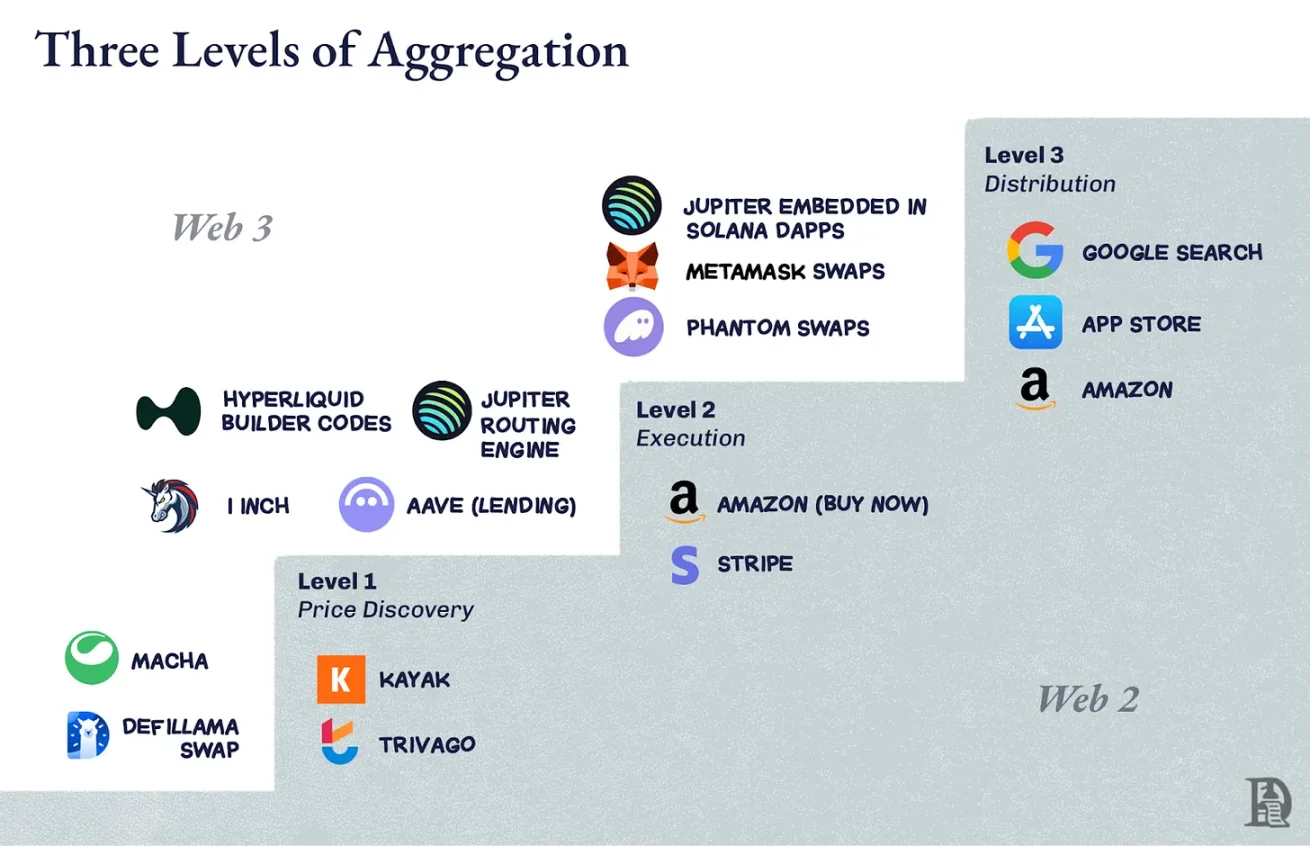

Note: The boundaries between different layers are often blurry. The classification is not precise but provides a mental model of aggregation layers.

First layer: Price discovery

This is the most fundamental work: telling people where the best trades are. Kayak is for flights, Trivago is for hotels. In the crypto space, early DEX aggregators like 1inch or Matcha fall into this category. They check available pools, display the best exchange rates, and provide jumping-off points. Price discovery is useful but fragile, as is DeFiLlama's exchange function.

If the underlying market is already concentrated (like Ethereum spot trading on Uniswap), routing improvements are minimal, and users can go directly to the trading venue; the help you provide is unnecessary.

Second layer: Execution

At this point, you no longer direct users elsewhere but operate on their behalf. Amazon's 'one-click purchase' falls into this layer. In DeFi, Aave's lending functionality is at this layer. When borrowing, liquidity already exists within its contracts. Execution increases stickiness because the results are directly relevant to you: quick settlements and good experiences with no failed transactions.

Third layer: Distribution control

You become the entry point. Google search for web pages, app stores for mobile applications, all fall into this category. In the crypto space, the exchange labels built into wallets can become the starting and ending point for average users.

On Solana, Jupiter has reached this layer. It started with price discovery tools, moved into execution through smart order routing, and then embedded itself into front-ends like Phantom and Drift. A significant portion of Solana's trading is actually Jupiter's trading, even if users never input 'jup.ag'. This is distribution control; suppliers cannot bypass you to reach users.

Climbing the layers in DeFi

The challenge in DeFi is that liquidity can shift rapidly. Incentives can drain pools overnight. Thus, ascending from the first to the third layer is not only about becoming a leading aggregator but also about creating sufficient reasons for liquidity and order flow to consistently pass through your routing.

On Ethereum, 1inch mainly stays on the second layer because Uniswap has completed aggregation work through centralized liquidity. Routing is still valuable for edge cases, but improvements are limited, and many traders choose to skip it. Additionally, aggregators like CowSwap and KyberSwap also occupy considerable shares. Aave belongs to the second layer as it controls execution in a niche, but it is infrastructure, not a starting point.

Jupiter's advantage on Solana lies in its ability to climb three layers sequentially. With liquidity dispersed, the value of the first layer is significant; the routing engine surpasses manual exchanges, naturally transitioning to the second layer; through direct integration with wallets and dApps, it reaches the third layer, fully controlling the distribution of Solana's liquidity. At one point, nearly half of Solana's computing usage came from Jupiter's trades, as both the demand side from traders and the supply side from liquidity pools relied on Jupiter.

Upon reaching the third layer, the question becomes, 'What else can be run through this distribution?' Amazon started with books and ended with everything; Google began with search and ultimately controlled maps, email, and cloud computing. For Jupiter, distribution is order flow. The obvious next step is to add products like perpetual contracts, lending, and portfolio tracking, leveraging the same liquidity relationships.

A larger move is Jupnet. Solana has yet to match Hyperliquid's throughput and execution characteristics, designed specifically for financial-grade latency and certainty. These characteristics are crucial for scaling the entire financial stack to real-world sizes. A simpler choice would be to launch products on chains that already possess these characteristics, but Jupiter chose the more challenging path of building Jupnet as a low-latency execution layer controlled by applications, running in parallel with Solana.

Jupnet aims to become shared infrastructure within the Solana ecosystem, supporting perpetual contracts, quote request systems, bulk auctions, and other latency-sensitive trades, ultimately settling natively on Solana. If successful, it will provide the speed and certainty expected of vertically integrated venues while retaining user and asset retention. This is an attempt to bridge the gap between general blockchain throughput and the global financial micro-latency demands, without needing to fragment liquidity cross-chain.

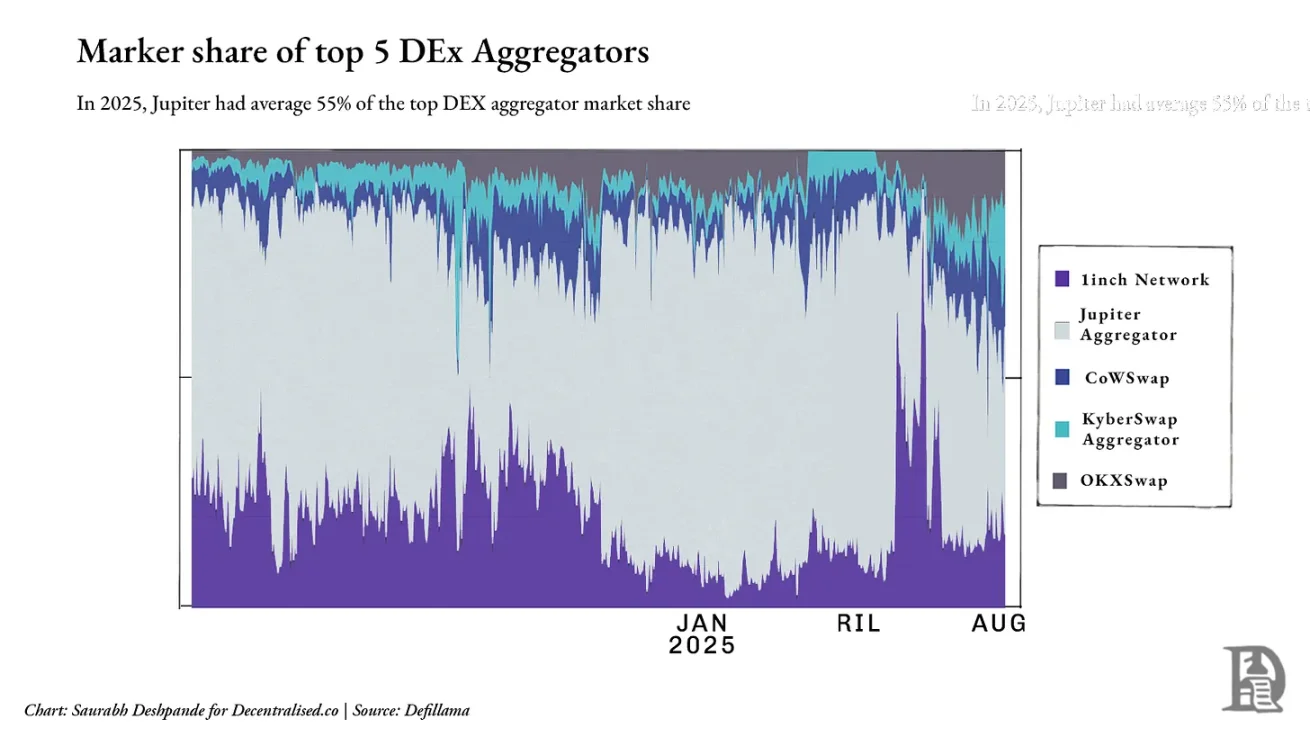

But it's worth noting: even though Jupiter holds a dominant position within Solana, the industry still faces fierce competition. In the cross-chain space, 1inch, CoWSwap, and OKX Swap maintain significant positions. By 2025, Jupiter is expected to average around 55% among the top five DEX aggregators, but that share fluctuates with on-chain activity and integrations. The chart below shows the degree of decentralization of aggregation layers outside of Solana.

Clearly, Jupiter has become the aggregator within the Solana ecosystem. The flywheel is in motion: more traders bring more liquidity, more liquidity optimizes execution, and better execution attracts more traders. At this point, you are not just a liquidity aggregator but also the shelf, habit, and market entry. So, when liquidity is no longer sufficient, how do you continue to grow? Jupiter's answer is to acquire projects that have already mastered new user flows.

M&A as a growth engine

Previously, I wrote about two main themes of scaling businesses: the nature of compound innovation and how companies accelerate this process through mergers and acquisitions. The former is about building new products, features, or capabilities based on existing advantages, while the latter is about identifying when 'buying' is faster than 'building' to establish an advantage.

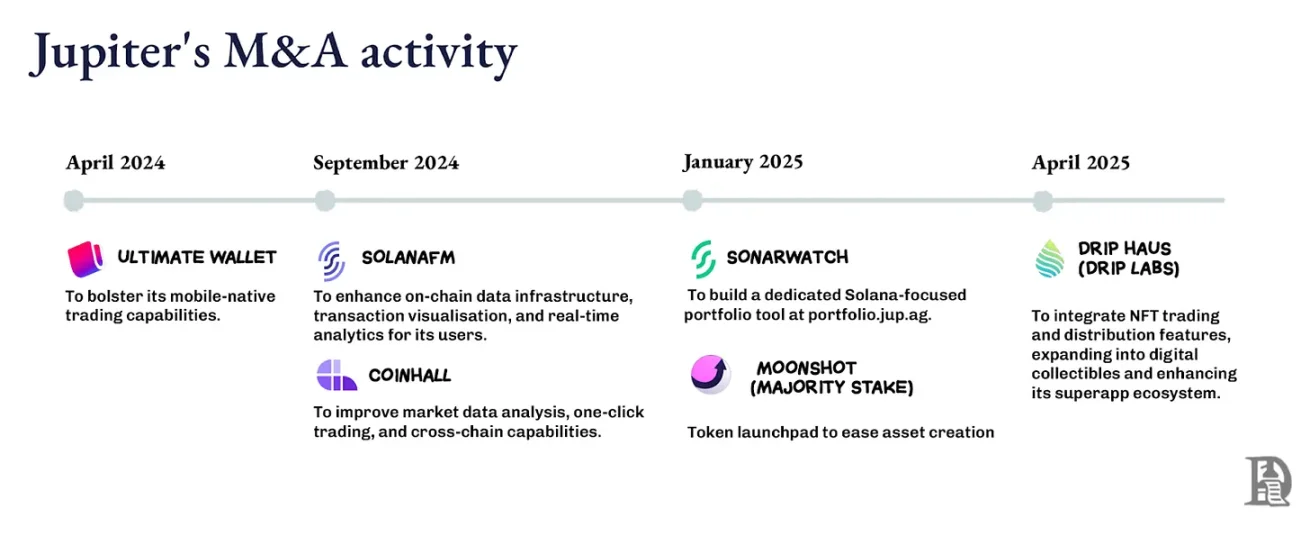

Jupiter's evolution embodies both. Its M&A strategy is rooted in finding founder teams with real appeal and integrating them into a distribution network that amplifies their influence. The company seeks teams of vertical experts to expand coverage without dragging down the core roadmap.

This is not just about purchasing feature overlaps but acquiring teams that have already dominated the market segments targeted by Jupiter. Once these teams plug into Jupiter's distribution wallet interface, API, and routing, their product growth accelerates, generating traffic that feeds back into Jupiter's core.

Moonshot brings token launch pads, transforming new token creation into direct exchanges and trading activities within the Jupiter ecosystem; DRiP adds a community-driven NFT minting and distribution platform, attracting audiences away from trading interfaces and converting them into on-chain behavior; Portfolio acquisition provides position management tools for active traders. Jupiter could have built these features internally at a lower cost, but its goal is to acquire founders, not just functionalities.

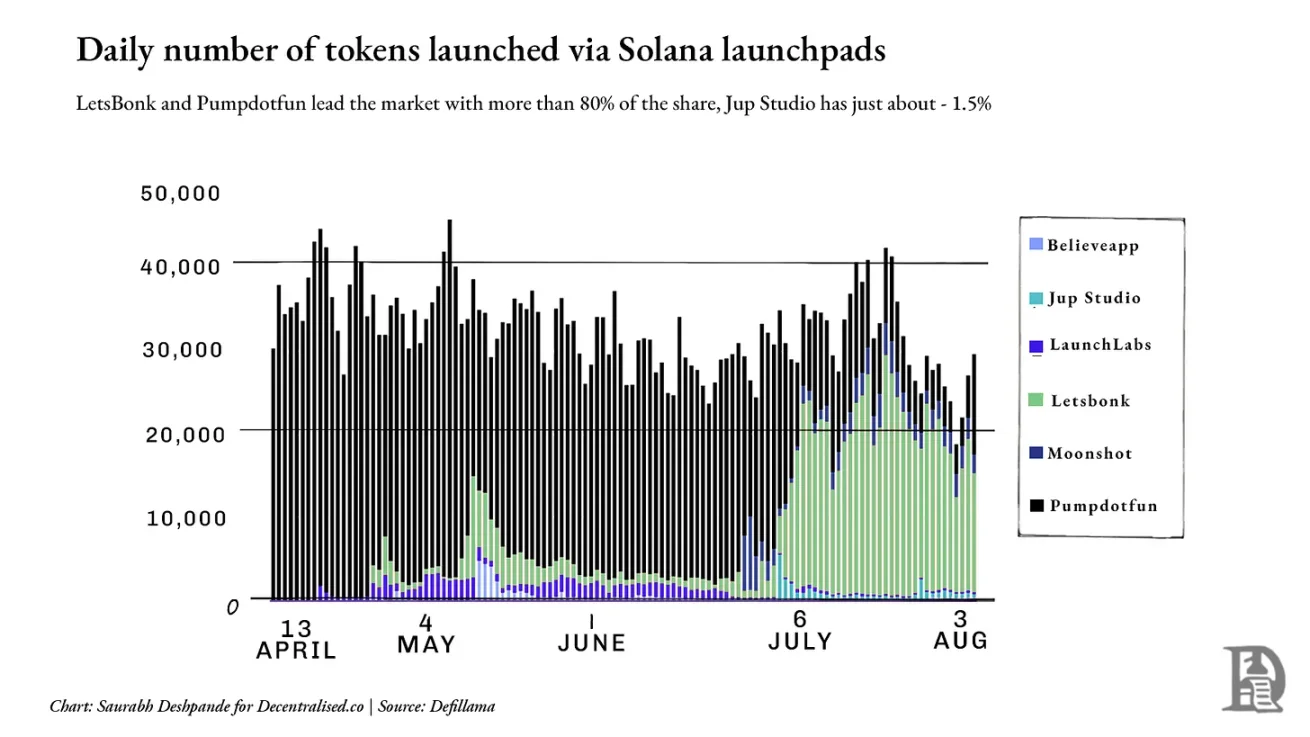

However, the growth of some metrics has yet to materialize. For instance, in the launchpad space, market leaders Pumpdotfun and LetsBonk control over 80% of daily token issuance, while Jup Studio and Moonshot together account for less than 10%. The chart below illustrates the incumbents' dominance. In this case, the default pattern may have solidified, and Jupiter may need a completely different approach to break through.

Force multipliers: Founder-led M&A

To broaden the shelf, you need to bring in operators who have already dominated the target market segments. Jupiter's selection criteria are: does the team bring new liquidity or users that strengthen the flywheel? This logic echoes Amazon's early flywheel: every new category or supplier expands 'choices,' optimizes customer experiences, drives more traffic, and thus attracts more suppliers.

For Jupiter, each acquisition is like adding a new shelf to the store, broadening choices and deepening connections with traders and liquidity providers.

Acquiring creative founders allows Jupiter to enter unfamiliar areas (such as the NFT culture of DRiP or mainstream retail token issuance) without diluting its core competencies. These founders understand the niche and have communities that trust them and can act quickly. Plugging into Jupiter's distribution channels amplifies their reach overnight while Jupiter gains new user flows and liquidity.

Acquisition cases illustrate this point: Moonshot is a minting and trading platform aimed at mainstream behavior, with tokens issued that can seamlessly transfer into exchanges, funding markets, and perpetual contracts within the Jupiter ecosystem; DRiP is a creator-first collectibles distribution channel that attracts communities that typically do not engage with trading interfaces.

Moonshot gained over 250,000 users within three days of launching the TRUMP token, processing over $1.5 billion in trading volume; DRiP attracted over 2 million collectors, minting over 200 million collectibles, with secondary sales exceeding 6 million transactions.

Integration follows a clear pattern: founders retain product direction authority; products go live and immediately connect to Jupiter's interface and backend, benefiting from its user base while Jupiter gains new traffic; each acquisition adds unique liquidity primitives (like issuance, culture, leverage) rather than duplicating existing features. The core competencies remain unchanged, and all paths still lead back to Jupiter.

In DeFi, code can fork overnight, but market share is hard to replicate. Founder-led M&A allows Jupiter to gain market share without losing its core path, making its flywheel harder to replicate. As applications control execution and low-latency infrastructure matures, Jupiter may target teams such as risk engines, matching layers, and specialty venues, integrating them into Jupnet.

Aggregator vs Supplier

Overall, two dominant models are emerging in DeFi: Jupiter and Hyperliquid. Both are powerful, but their strategies are completely different.

Hyperliquid aims to control liquidity rather than directly own end-user relationships. It provides liquidity as a service. If it can build a better user experience, users are welcome to utilize Hyperliquid's order book and execution engine. Builder Codes is based on this concept, where others can own the front-end experience while Hyperliquid quietly supports the backend, which is a supplier-first model.

Jupiter focuses on distribution; it aims to own the interface, shelf, and market entry, aggregating dispersed liquidity by becoming the default interface and directing it where needed. This means controlling user relationships, not just execution tracks. From perpetual contracts to portfolios, Jupiter tries to make all financial interfaces begin and end within its track.

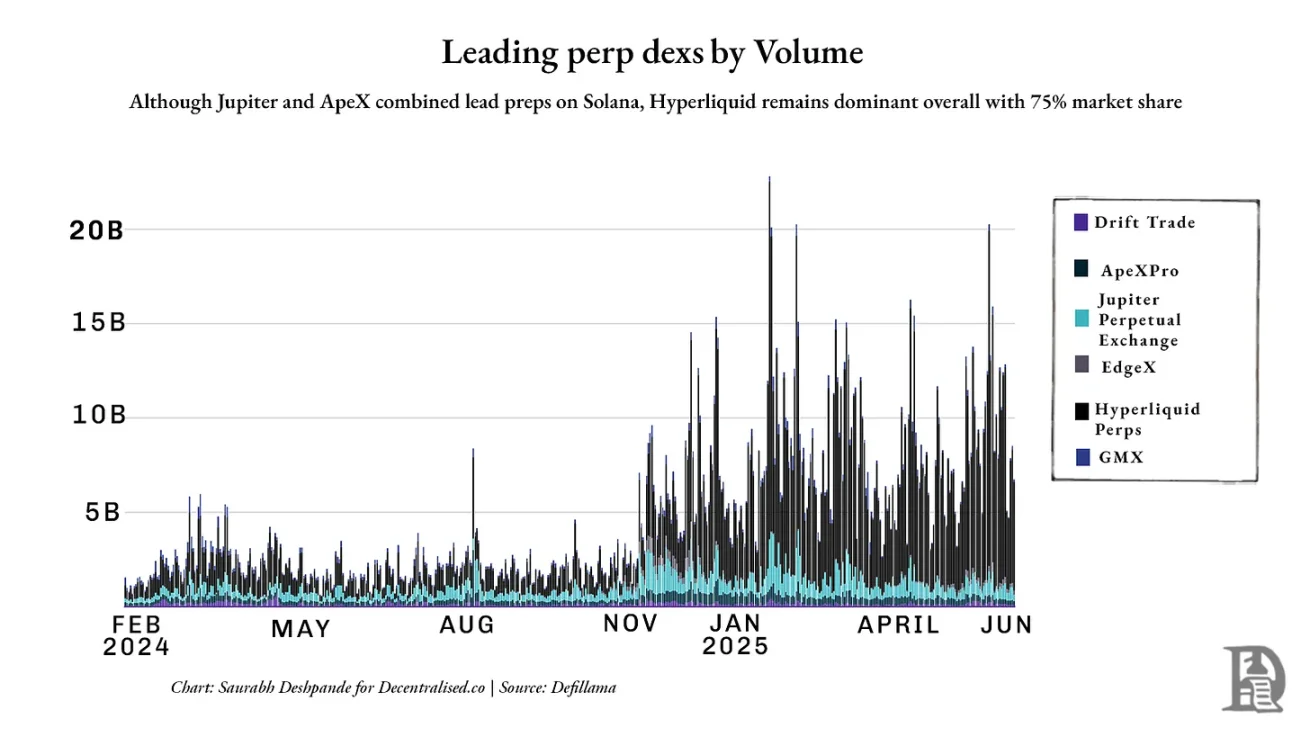

However, perpetual contracts may expose the current limitations of this strategy the most. Jupiter has made progress on Solana, but Hyperliquid still dominates the market with around 75% of the perpetual DEX market share. The chart below shows Hyperliquid's lead in original trading volume:

Both models bet on scale but start from opposite ends. Jupiter believes liquidity follows user interface; Hyperliquid believes liquidity is the interface. Jupiter builds entry points, while Hyperliquid builds endpoints.

In practice, we witness differentiation: if extensive interface and user aggregation are needed, choose Jupiter; if depth, certainty, and composability are required, choose Hyperliquid. One turns liquidity into dependency networks, while the other becomes the underlying layer built by the masses.

Winners are not just the first arrivals but those that others cannot forsake.

This is precisely what makes DeFi exciting right now. We are witnessing a philosophical showdown: one side believes distribution is the moat, while the other firmly believes liquidity is.

Applications as new platforms

When Ethereum Layer 2 first emerged, there was hope it would become a new platform: a neutral ground for applications to be composable, competitive, and scalable. But it turns out that L2 has not become the platform envisioned, but rather remains at the infrastructure level: providing the technical basis for speed, security, and scalability without controlling user relationships.

Platforms serve as the starting point of the user journey, where demand aggregates, habits form, and distribution survives. Few L2s cross this line; most serve as pipelines rather than shelves, rarely building meaningful distribution and even more seldom becoming the default entry point for users.

In contrast, applications like Jupiter and Hyperliquid are gradually manifesting platform characteristics. They possess user relationships, embed themselves into daily habits, and reinforce their positions through acquisitions or integrations with other applications. In fact, they are beginning to resemble Web2.

Google moved beyond search engines by acquiring YouTube, transforming its search advantage into a video dominance; Facebook expanded its control over attention by acquiring Instagram and WhatsApp. They targeted adjacent areas where they were absent but where users had already gathered, and crucially, they acquired the core players in those areas. Once acquired, these applications could immediately access Google's and Facebook's existing distribution flywheel, resulting in capturing multi-channel user attention.

Jupiter is running a similar strategy. Launchpads, NFT minting tools, portfolio managers, and now Jupnet, all serve the same purpose: expanding coverage, capturing more user behavior, and routing more liquidity to itself. Its strategy is to become the shelf, the default choice, and the starting point for financial interactions.

But aggregation is not a surefire strategy. History is filled with failed platform acquisitions and aggregation attempts, either due to a lack of user relationships or misunderstanding how habits form.

Take Microsoft's acquisition of Nokia as an example. This was a bet on controlling mobile distribution, but users had already shifted to iOS and Android ecosystems. Microsoft had the hardware and software, but its mobile devices and operating system were either too similar to existing products or insufficient to prompt user switching. It did not control the application layer or earn developer loyalty, nor did it provide a reason to change behavior. A lack of control over supply or clear differentiation left the shelf unattended.

These cases reflect the core truth: acquisitions alone do not create a flywheel. Without a starting point, habit, or interface, no matter how many features are bundled, users will not follow.

This makes DeFi especially interesting at the current moment. Jupiter acquires front-end, distribution channels, and liquidity primitives in an attempt to become the default entry point for the Solana financial stack; Hyperliquid does the opposite: building depth rather than breadth, allowing others to revolve around its portfolio.

In a sense, we are witnessing a true platform war unfolding between applications, rather than between public chains as many expected. This raises a bigger question: if L2 does not control distribution, when the applications on it do, where will the value flow? What will happen to fat protocols?

We conclude with unresolved questions, as there are no definitive answers. In the future, we will bring sharper insights, new data points, and more stories and analogies to clarify the direction of all this.