Written by: Prathik Desai

Compiled by: Block unicorn

In the 20th century, Augusta National Golf Club was criticized for its blatant elitism. As the host of the Masters Tournament, the club had only 300 members, and the admission process was extremely strict, even disallowing potential members from applying directly. Membership had to be obtained by invitation. Another way was through nomination, followed by a patient wait.

Critics labeled it the ultimate 'men's club,' which it certainly was before 2012. Worse yet, for decades, the club banned African Americans from becoming members. Sports journalists questioned why the most prestigious event in golf would be held at a venue that excluded 99.9% of humanity. Public perception was extremely poor: a small group of wealthy white males controlled opportunities that millions yearned to experience.

The club prides itself on having some famous members, including four-time Masters champion Arnold Palmer, business magnates Warren Buffett and Bill Gates, and the 34th President of the United States, Dwight D. Eisenhower.

Clearly, this is not the most democratic way to operate a club.

But why would Augusta National Golf Club pursue the popularization of world-class golf courses? Open access rarely creates high-end brands. The club pursues excellence. With only 300 members and almost no external players, the course remains pristine year-round. Every detail is managed with great precision.

For example, it can bear the rigorous maintenance required by the legend of the Augusta National Golf Club brand. Think about it: hand-trimming the fairways with scissors, coloring the pine needles, and moving entire groves of trees for the perfect television angle. Fewer stakeholders mean higher precision. Quality can only be perfected when access is controlled.

The same logic explains one of the most misunderstood trends in today's cryptocurrency space: why real-world asset (RWA) tokens—digital representations ranging from government bonds to real estate—are predominantly held by a small number of wallets.

But the exclusivity here is not based on gender or race.

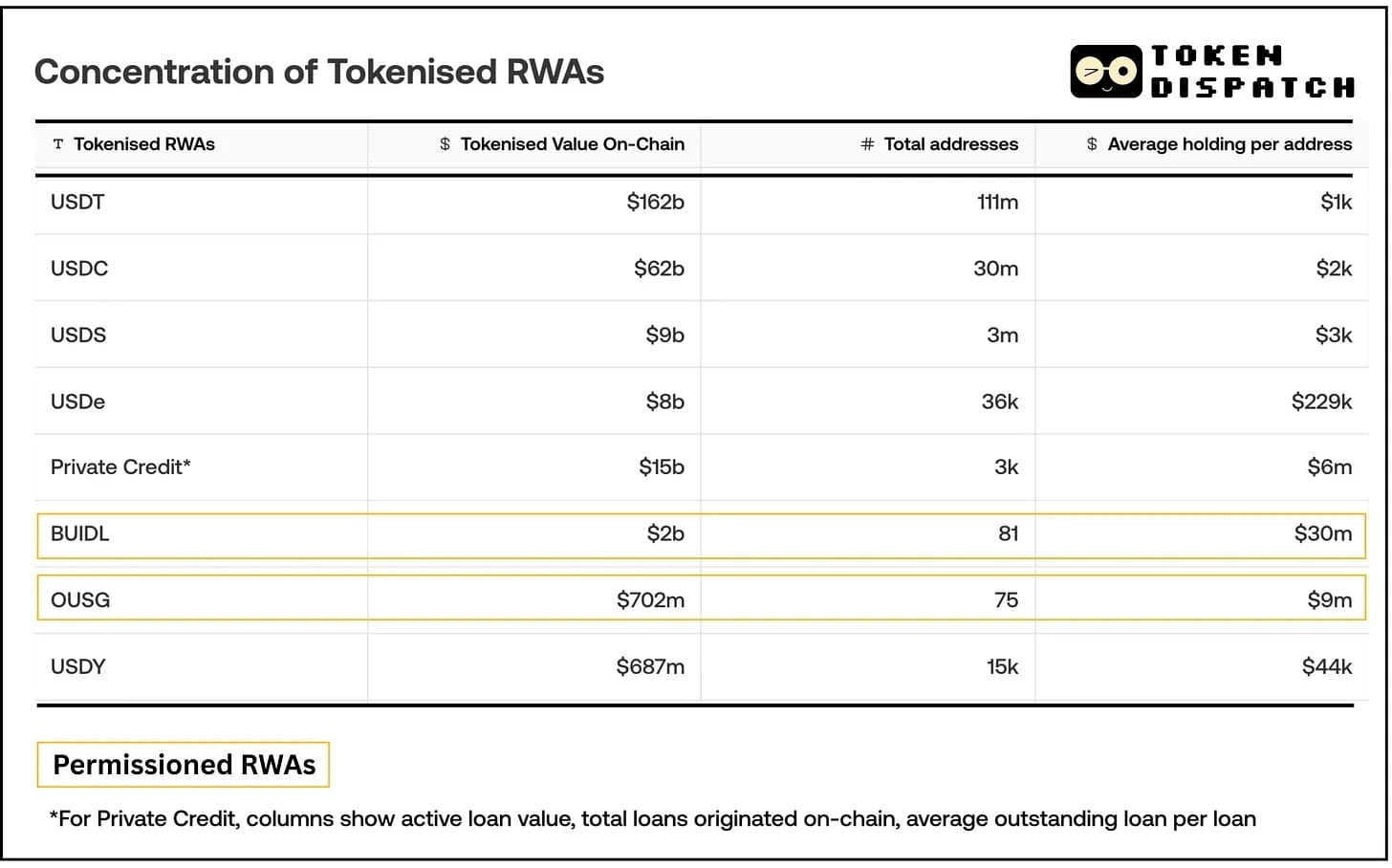

BlackRock's tokenized money market fund BUIDL (BlackRock U.S. Dollar Institutional Digital Liquidity Fund) has approximately $2.4 billion in assets, but as of July 31, 2025, it has only 81 holders.

Similarly, Ondo Finance's U.S. Treasury fund OUSG (Ondo Short-Term U.S. Government Bond Fund) shows only 75 holders on-chain. In contrast, major stablecoins like USDT/USDC are held by millions of addresses (approximately 175 million stablecoin holders across networks).

At first glance, these digital dollar assets seem to encapsulate all the problems that blockchain was supposed to solve: centralization, gatekeeping mechanisms, exclusivity. If you can copy and paste a wallet address, why can't you purchase these yield-generating tokens just like other crypto assets?

The answer lies in the same operational logic that allows Augusta National Golf Club to maintain its exclusivity. The design of these tokens is centralized.

The reality of regulation

The history of financial exclusivity is often a story about maintaining privilege through exclusion. But in these cases, exclusivity serves a different purpose: to keep the system compliant, efficient, and sustainable.

Most RWA tokens represent securities or funds that cannot be offered freely to the public without registration. Instead, issuers use private or limited offerings regulated by the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), such as Regulation D in the U.S. or Reg S abroad, restricting tokens to accredited or compliant investors.

BUIDL (BlackRock) offered through Securitize is only open to U.S. qualified purchasers (a subset of accredited investors, with a minimum investment of approximately $5 million).

Similarly, Ondo's OUSG (tokenized treasury fund) requires investors to be both accredited investors and qualified purchasers.

These are not arbitrary barriers. They are requirements verified by the SEC under Regulation D 506(c), determining who can legally own certain types of financial instruments.

When we observe tokens designed for different regulatory frameworks, the contrast becomes clearer. Ondo's USDY is only targeted at non-U.S. investors (sold overseas under Reg S). By circumventing U.S. restrictions, it achieves broader distribution, allowing non-U.S. individuals who complete KYC to purchase USDY. The number of USDY holders is 15,000, which, while not large, far exceeds OUSG's 75.

The same company, the same tokenized asset, just different regulatory frameworks. The result is a distribution difference of up to 200 times.

This is where the comparison between Augusta National Golf Club and RWA becomes precise. To achieve the aforementioned objectives, RWA token platforms integrate compliance into the token code or surrounding infrastructure. Unlike freely tradable ERC-20 tokens, these tokens are often subject to transfer restrictions at the smart contract level.

Most security tokens adopt a whitelist/blacklist model (through standards such as ERC-1404 or ERC-3643), where only pre-approved wallet addresses can receive or send tokens. If an address is not on the issuer's whitelist, the token's smart contract will block any transfer to that address.

It's like a guest list executed by code. You cannot just show up at the door with a wallet address and demand entry. Someone must verify your identity, check your accredited investor status, and add you to the approved list. Only then will the smart contract allow you to receive tokens.

Backed Finance's tokens come in two forms—an unrestricted version and a packaged 'compliant' token. Packaged tokens 'only allow whitelisted addresses to interact with the tokens,' and Backed will automatically add users to the whitelist after they complete KYC.

Efficiency argument

From the outside, the system appears exclusive. From the inside, it appears efficient. Why? From the issuer's perspective, given their business model and constraints, a centralized holder base is often a rational, even intentional choice.

Each additional token holder represents a potential compliance risk and additional costs, whether on-chain or off-chain. Despite these upfront compliance costs, on-chain rails bring long-term operational efficiencies, particularly in terms of instant settlement compared to traditional markets' T+2 and programmability (like automatic interest distribution).

By implementing tokenization and deploying distributed ledger technology (DLT), asset managers can reduce operational costs by 23%, equivalent to 0.13% of assets under management (AUM), as stated in the white paper by global fund network Calastone.

It predicts that tokenization could help the average fund improve its profit and loss statement, increasing profits by $3.1 million to $7.9 million, including an additional $1.4 million to $4.2 million in revenue through a more competitive total expense ratio (TER).

The entire asset management industry can achieve a total saving of $135.3 billion across UCITS, UK, and US (40 Act) funds.

By limiting distribution to known and vetted participants, issuers can more easily ensure that each holder meets the requirements (accredited investor status, jurisdiction checks, etc.) and reduce the risk of tokens accidentally falling into the hands of bad actors.

Mathematically, this also makes sense. By targeting a few large investors instead of many small ones, issuers can save on onboarding costs, investor relations, and ongoing compliance monitoring expenses. For a $500 million fund, reaching capacity with five investors each contributing $100 million is much more commercially viable than 50,000 investors each contributing $10,000. The management of the former is also much simpler. While on-chain transfers settle automatically, the compliance layer involving KYC, accreditation, and whitelisting remains off-chain and scales linearly with the number of investors.

Many RWA token projects are explicitly aimed at institutional or corporate investors rather than retail. Their value proposition often revolves around providing crypto-native yield channels for fund managers, fintech platforms, or crypto funds with large cash balances.

When Franklin Templeton launched its tokenized money market fund, they did not intend to replace your bank checking account. They wanted to provide a way for CFOs of Fortune 500 companies to earn yield on their idle corporate cash reserves.

The exception for stablecoins

At the same time, comparisons with stablecoins are not entirely fair, as stablecoins address regulatory challenges in different ways. USDC and USDT themselves are not securities, designed as digital representations of the dollar rather than investment contracts. This classification is achieved through careful legal structuring and regulatory involvement, allowing them to circulate freely without investor restrictions.

But even stablecoins require massive infrastructure investments and regulatory clarity to achieve their current scale of distribution. Circle spent years building compliance systems, working with regulators, and establishing banking relationships. The 'permissionless' experience users enjoy today is built on a highly permissioned foundation.

RWA tokens face different challenges: they represent actual securities with tangible investment returns and are thus subject to securities law. Until there is a clearer regulatory framework for tokenized securities (the recently passed GENIUS Act begins to address this issue), issuers must operate within existing restrictions.

Future outlook

The current centralization of RWA tokens is, after all, the closest representation of how traditional finance operates. Consider traditional private equity funds or bond issues limited to accredited institutional buyers, where participants are typically restricted to a small number of investors.

The difference lies in transparency. In traditional finance, you do not know how many investors hold a particular fund or bond—this information is private. Only large holders need to make regulatory disclosures. On-chain, every wallet address is visible, making centralization evident.

Moreover, exclusivity is not a characteristic of on-chain tokenized assets. This has always been the case. The value of RWA tokenization lies in making these funds easier for issuers to manage.

Figure's digital asset registration technology (DART) reduces the loan due diligence cost from $500 per loan to $15, while shortening settlement time from weeks to days. Goldman Sachs and Jefferies can now easily purchase loan pools as if trading tokens. Meanwhile, tokenized treasuries like BUIDL suddenly become programmable, allowing you to use these ordinary government bonds as collateral to trade Bitcoin derivatives on Deribit.

Ultimately, the noble goal of democratizing access can be achieved through a regulatory framework. Exclusivity is a temporary regulatory friction. Programmability is a permanent infrastructure upgrade that makes traditional assets more flexible and tradable.

Back at Augusta National Golf Club, their controlled membership model makes the golf championship a perfect synonym. The limited number of members means that every detail can be managed precisely. Exclusivity creates conditions for excellence, but paradoxically, it also makes it more cost-effective. Providing the same precision and hospitality for a broader, more inclusive audience would exponentially increase costs.

A controlled holder base also creates conveniences for fund issuers to ensure compliance, efficiency, and sustainability.

However, the barriers on-chain are gradually lowering. As regulatory frameworks evolve, packaged products emerge, and infrastructure matures, more people will gain access to these benefits. In some cases, this access may be achieved through intermediaries and products designed for broader distribution (such as Backed Finance's unrestricted version) rather than direct ownership of the underlying tokens.

The story is still in its early stages, but understanding why things look the way they do today is key to understanding the impending transformation.