The notion that cryptocurrency has yet to produce any noteworthy innovations has long since become outdated.

Written by: The Economist

Compiled by: Centreless, Deep Tide

One thing is clear: the notion that cryptocurrency has yet to produce any noteworthy innovations has long since become outdated.

In the eyes of the conservatives on Wall Street, the 'use cases' of cryptocurrency are often discussed with a tone of ridicule. The veterans have seen it all before. Digital assets come and go, often with great fanfare, exciting those investors keen on memecoins and NFTs. Beyond being used as tools for speculation and financial crime, their other applications have repeatedly been found to have flaws and shortcomings.

However, the latest wave has been different.

On July 18, President Donald Trump signed the GENIUS Act (Stablecoin Act), providing long-desired regulatory certainty for stablecoins (crypto tokens backed by traditional assets, usually the dollar). The industry is currently thriving; Wall Street is now racing to get involved. 'Tokenization' is also on the rise: on-chain asset trading volumes are rapidly increasing, including stocks, money market funds, and even private equity and debt.

As with any revolution, revolutionaries are ecstatic while conservatives are anxious.

Vlad Tenev, CEO of digital asset brokerage Robinhood, stated that this new technology could 'lay the groundwork for cryptocurrency to become a pillar of the global financial system.' The perspective of European Central Bank President Christine Lagarde is somewhat different. She is concerned that the emergence of stablecoins is akin to 'the privatization of money.'

Both sides are aware of the scale of change at hand. Currently, the mainstream market may face a disruption more significant than the early speculation in cryptocurrencies. Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies promise to become digital gold, while tokens are merely wrappers or vehicles representing other assets. This may not sound remarkable, but some of the most transformative innovations in modern finance have indeed changed the ways assets are packaged, sliced, and restructured—exchange-traded funds (ETFs), Eurodollars, and securitized debt are typical use cases.

Currently, the circulating value of stablecoins stands at $263 billion, an increase of about 60% from a year ago. Standard Chartered Bank predicts that market value will reach $2 trillion in three years.

Last month, JPMorgan Chase, the largest bank in the U.S., announced plans to launch a stablecoin-like product called JPMD, despite CEO Jamie Dimon's long-standing skepticism about cryptocurrencies.

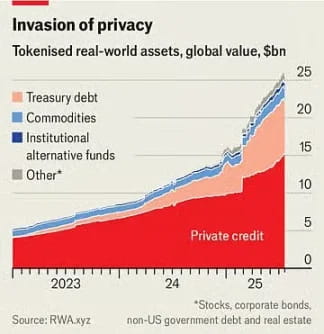

The market value of tokenized assets is only $25 billion, but it has more than doubled in the past year. On June 30, Robinhood launched over 200 new tokens for European investors, allowing them to trade U.S. stocks and ETFs outside normal trading hours.

Stablecoins make transactions cheap and quick because ownership is instantly recorded on a digital ledger, eliminating the intermediary institutions that operate traditional payment channels. This is particularly valuable for currently costly and slow cross-border transactions.

Although stablecoins currently account for less than 1% of global financial transactions, the GENIUS Act will provide a boost. The act confirms that stablecoins are not securities and requires that stablecoins must be fully backed by safe, liquid assets.

Retail giants, including Amazon and Walmart, are reportedly considering launching their own stablecoins. For consumers, these stablecoins might resemble gift cards, providing balances for spending at retailers and potentially at lower prices. This could eliminate companies like Mastercard and Visa, which facilitate profit margins of about 2% on sales in the U.S.

Tokenized assets are digital copies of another asset, whether it be a fund, company stock, or a basket of goods. Like stablecoins, they can make financial transactions faster and easier, especially for trades involving illiquid assets. Some products are just gimmicks. Why tokenize stocks? Doing so may enable 24-hour trading since the exchanges where stocks are listed do not need to be open, but the advantages of doing so are questionable. Moreover, for many retail investors, marginal trading costs are already low, even zero.

Efforts to tokenize

However, many products are not that fancy.

Take money market funds, for example, which invest in treasury bills. A tokenized version can also serve as a means of payment. These tokens, like stablecoins, are backed by safe assets and can be seamlessly exchanged on the blockchain. They also represent an investment superior to bank interest rates. The average interest rate on U.S. savings accounts is less than 0.6%; many money market funds yield as much as 4%. The largest tokenized money market fund managed by BlackRock is currently valued at over $2 billion.

'I expect that one day, tokenized funds will be as familiar to investors as ETFs,' wrote Larry Fink, the CEO of the company, in a recent letter to investors.

This would have a disruptive impact on existing financial institutions.

Banks may be trying to enter the new digital packaging realm, but part of their motive is the realization that tokens pose a threat. The combination of stablecoins and tokenized money market funds could ultimately reduce the allure of bank deposits.

The American Bankers Association points out that if banks lose about 10% of their $19 trillion retail deposits (the cheapest source of funding), their average funding cost would rise from 2.03% to 2.27%. While the total amount of deposits, including commercial accounts, would not decrease, banks' profit margins would be squeezed.

These new assets could also have disruptive effects on the broader financial system.

For example, holders of Robinhood's new stock tokens do not actually own the underlying stocks. Technically, they own a derivative that tracks the asset's value (including any dividends paid by the company), rather than the stock itself. Therefore, they cannot obtain the voting rights usually conferred by stock ownership. If the token issuer goes bankrupt, holders will find themselves in a predicament, needing to compete with other creditors of the defunct company for ownership of the underlying assets. A fintech startup called Linqto, which filed for bankruptcy earlier this month, faced a similar situation. The company had issued shares of private companies through special purpose vehicles. Buyers are now unclear if they own the assets they thought they did.

This is one of the biggest opportunities for tokenization, but it also poses the greatest challenges for regulators. Pairing illiquid private assets with easily tradable tokens opens a closed market to millions of retail investors who have trillions of dollars to allocate. They could buy shares in the most exciting private companies that are currently out of reach.

This raises questions.

Institutions like the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) have a far greater influence over publicly traded companies than over private ones, which is why the former are suitable for retail investors. Tokens representing private shares would turn once-private equity into assets that can be traded as easily as ETFs. However, ETF issuers promise to provide intraday liquidity through trading the underlying assets, while the providers of tokens do not. At a sufficiently large scale, tokens would effectively turn private companies into public ones without the usual disclosure requirements.

Even regulators supportive of cryptocurrency want to draw a line.

Hester Peirce, a commissioner of the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), is referred to as the 'Crypto Mom' for her friendly stance on digital currencies. In a statement on July 9, she emphasized that tokens should not be used to circumvent securities laws. 'Tokenized securities are still securities,' she wrote. Therefore, companies issuing securities must comply with information disclosure rules, regardless of whether the securities are wrapped in new cryptocurrency packaging. While this is theoretically reasonable, the multitude of new assets with new structures means that regulators will be endlessly in a state of catch-up in practice.

Thus, there exists a paradox.

If stablecoins are truly useful, they will also be genuinely disruptive. The greater the appeal of tokenized assets to brokers, clients, investors, merchants, and other financial companies, the more they can transform finance, a change that is both exciting and concerning. Regardless of how the balance between the two is struck, one thing is clear: the notion that cryptocurrency has yet to produce any noteworthy innovations has long since become outdated.