Written by: Joel John, Sumanth Neppalli, Decentralised.co

Compiled by: AididiaoJP, Foresight News

Cryptocurrency has now become true fintech.

This article explores how legislative changes will unbundle traditional banks. If blockchain is the money track and everything is a market, users will ultimately leave idle deposits in their preferred applications. In turn, this will accumulate balances in applications with great distribution capabilities.

In the future, everything could be a bank, but how will that happen?

(The GENIUS Act) allows applications (in the form of stablecoins) to hold dollars on behalf of users. It opens the incentive switch for platforms, encouraging users to deposit funds and consume directly through the application. But banks are not just vaults for storing dollars; they are complex databases layering logic and compliance. In today's discussion, we explore how the tech stack supporting this shift has evolved.

Most fintech platforms we use are essentially wrappers around the same batch of underlying banks. So, we are no longer chasing the next shiny payment product but starting to build direct relationships with the banks themselves.

You cannot build a startup on top of another startup. You need to establish direct relationships with entities that actually do the work, so if something goes wrong, you are not stuck playing a game of telephone among layers of middlemen. As a founder, choosing a stable yet slightly traditional vendor can save you hundreds of hours and just as many back-and-forth emails.

In banking, most profits come from where the money is. Traditional banks hold billions in user deposits and may have internal compliance teams. Compared to a founder worried about their license, banks may be a safer choice.

But at the same time, sitting in the middle layer where assets turn over frequently can also generate huge profits. Robinhood does not 'hold' stock certificates, and most trading terminals in cryptocurrency do not host users' assets. Yet they generate billions in fees each year.

These are two contrasting forces in the financial world, a tug-of-war between those wanting custody and those wanting to be the layer where transactions occur. Your traditional bank might feel conflicted allowing you to trade meme coins with assets they are custodians of, as they profit from deposits. Meanwhile, exchanges profit by convincing you that wealth comes from betting on the next meme token.

This friction lies behind the ever-evolving concept of the portfolio. In contrast, a savvy 27-year-old today might consider her Ethereum, rights to Sabrina Carpenter’s music, and streaming dividends from (My Oxford Year) as safe supplements to her portfolio, alongside gold and stock certificates. While rights and streaming dividends do not exist as tangible assets yet, the ongoing evolution of smart contracts and regulations will likely make them possible in the next decade.

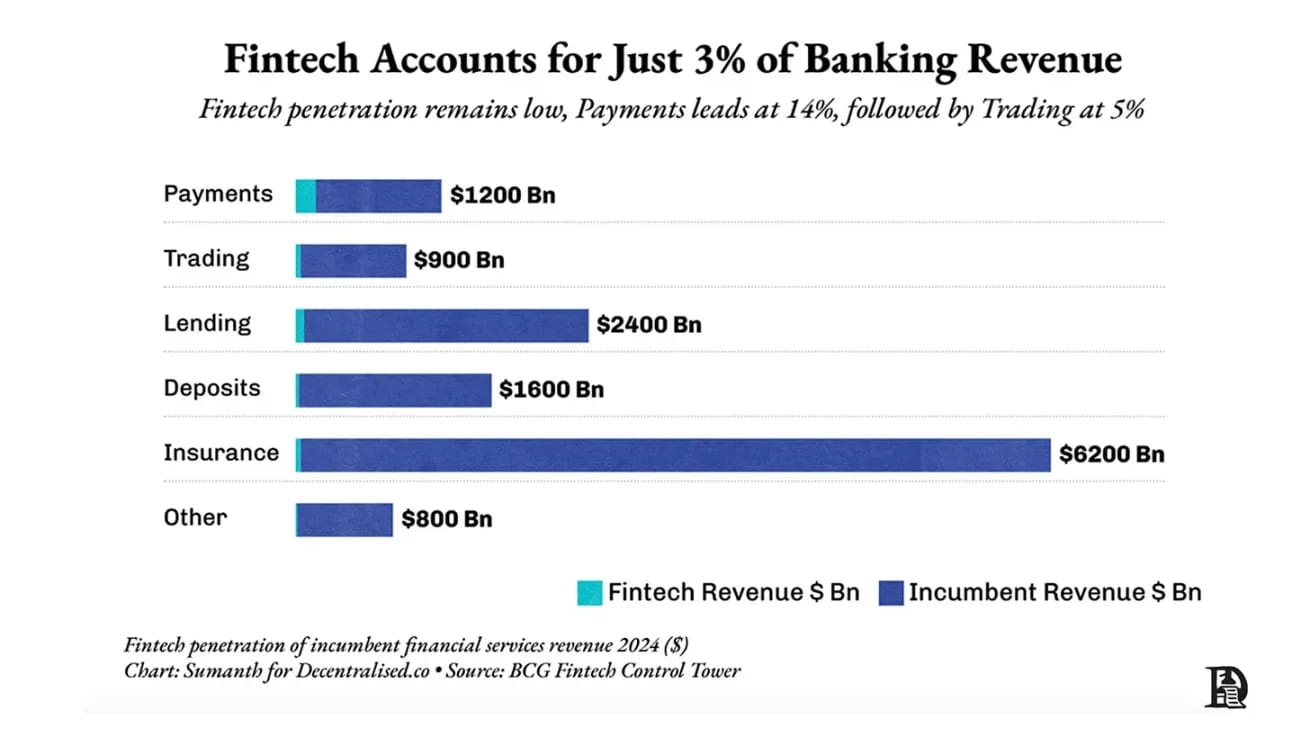

If the definition of a portfolio changes, then where we store wealth will also change. Few places illustrate this transformation as clearly as today's banks. Banks capture 97% of all banking revenue, leaving only about 3% for fintech platforms. This is a classic Matthew effect, where banks generate most revenue because most capital is stored with them today. But can business be built by peeling off parts of the monopoly and having specific functions?

We tend to think so. This is also part of the reason why half of our portfolio consists of fintech startups.

Today's article aims to argue for the unbundling of banks.

New banks are not in shiny offices in city centers; they are in your social information streams, in your applications. Cryptocurrencies have reached a level of maturity where they are no longer just associated with early adopters. They have begun to flirt with the boundaries of fintech, allowing us to build things with the world as the total addressable market (TAM). What does this mean for investors, operators, and founders?

We are trying to find answers in today's discussion.

The GENIUS Act in liquidity

Warren Buffett is dubbed the Oracle of Omaha for good reason; his investment portfolio has been nothing short of miraculous. But behind this miracle lies some often-overlooked financial engineering. Berkshire Hathaway owns something that can be seen as permanent capital. In 1967, he acquired an insurance business with stable idle capital. In insurance terms, he could leverage the float, which is the amount of premiums paid but not yet claimed, and think of it as an interest-free loan.

Contrast that with most fintech lending platforms. LendingClub is a startup focused on peer-to-peer lending. In this model, liquidity comes from other users on the platform. If I loan money to Saurabh and Sumanth on LendingClub, and neither repays, I may be less willing to loan money to Siddharth on the same platform. That’s because by then, my trust in the platform's ability to vet, verify, and bring in quality borrowers has weakened.

If you have an accident every time you take a ride, would you still use Uber?

Think of this, but replace it with lending. LendingClub eventually had to acquire Radius Bank for $185 million to gain a stable source of deposits that could be used for lending.

Similarly, SoFi spent nearly $1 billion over seven years to scale as a non-bank lender. Without a banking license, you are not allowed to take deposits and lend them out to prospective borrowers. So it had to provide loan funding through partner banks, which consumed most of the interest generated. Think of it as borrowing money from Saurabh at a 5% interest rate and lending it to Sumanth at a 6% rate. This 1% spread is my profit for issuing that loan. But if I had a stable source of deposits (like a bank), I could earn more.

That is ultimately what SoFi did. In 2022, it acquired Sacramento's Golden Pacific Bank for $22.3 million. This move was to obtain a license that allowed it to accept deposits. This change pushed its net interest margin to about 6%, well above the typical 3-4% for U.S. banks.

Smaller bank wrappers can't generate enough profit margins to operate. What about giants like Google? Google launched Plex as a mechanism to embed a wallet directly into your Gmail app. It was built in collaboration with a bank consortium to handle deposits. The business involved Citigroup and Stanford Federal Credit Union, but it never launched. After two years of regulatory back-and-forth, Google scrapped the project in 2021. In other words, you could have the world's largest inbox, but it’s hard to convince regulators why people should be allowed to transfer money at the place where they send and receive emails; that’s just life.

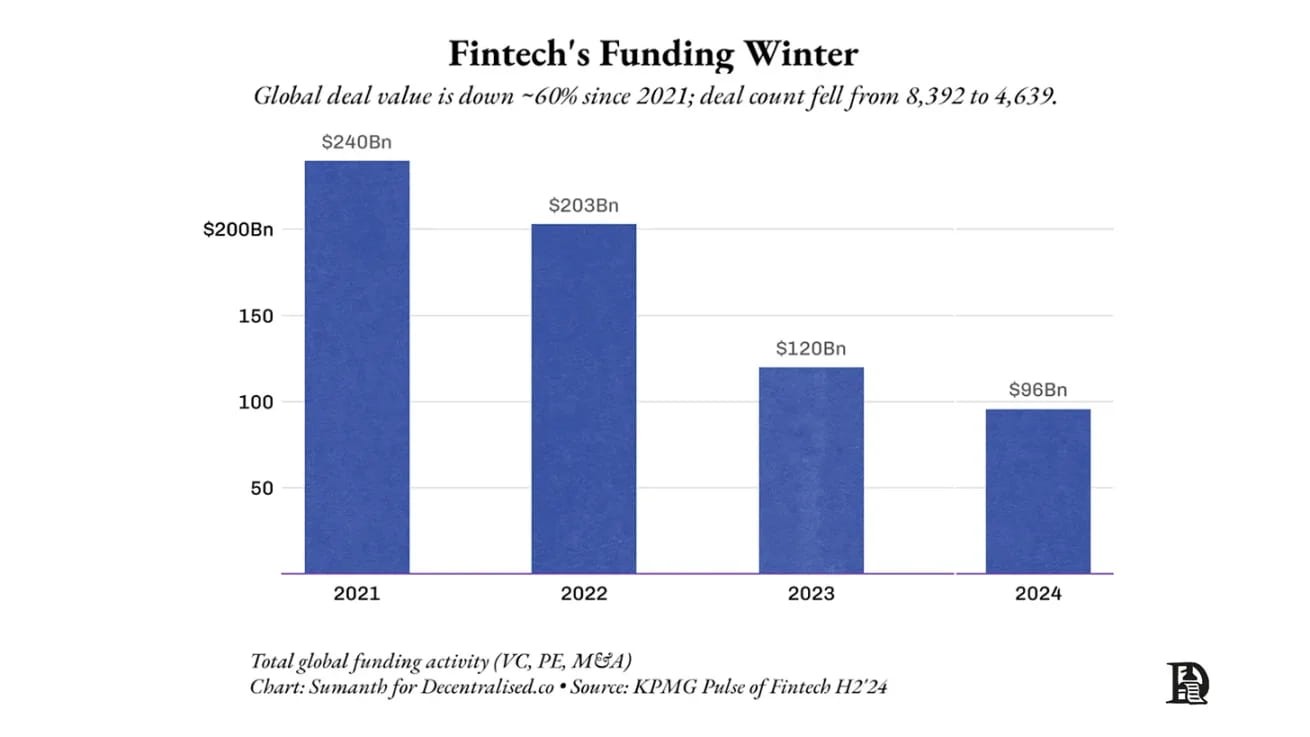

Venture capital understands this struggle. Funding for fintech startups has halved since 2021. Historically, most of the moat for fintech startups was regulatory. That’s why banks capture the largest share of the banking revenue pie. But when banks misprice risk, they are gambling with depositors' money, as we saw with Silicon Valley Bank.

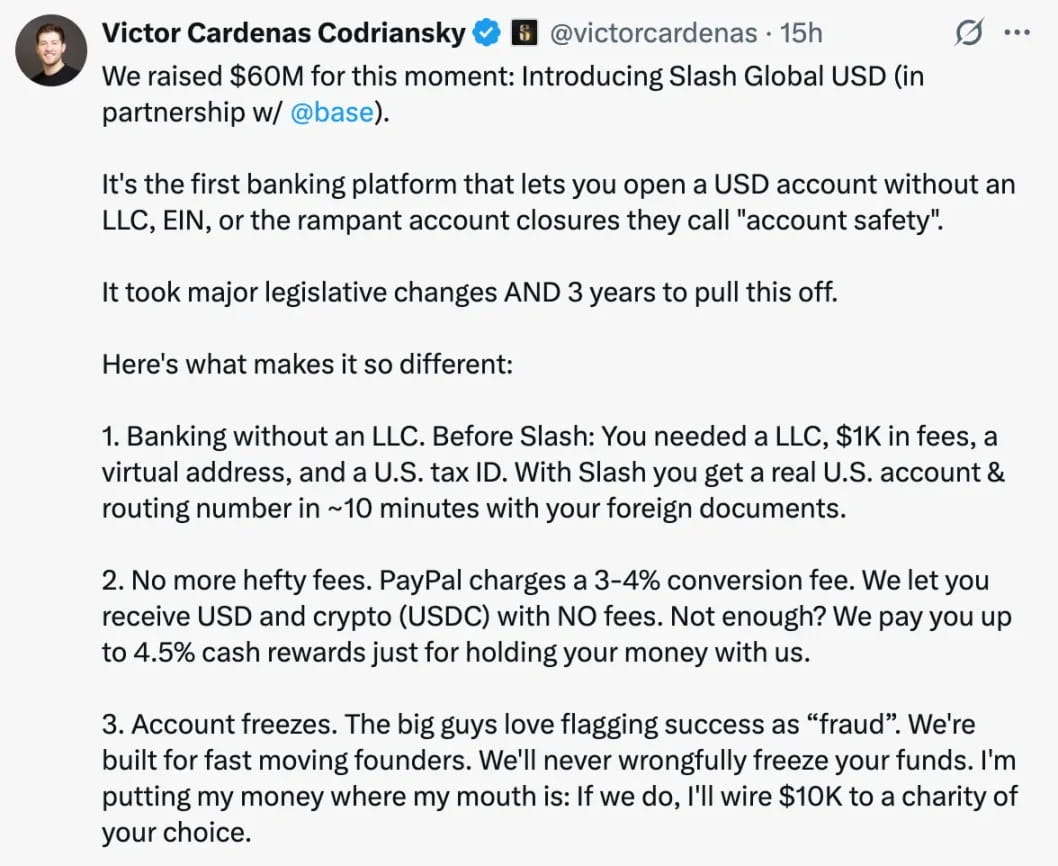

(The GENIUS Act) erodes this moat. It allows non-bank institutions to hold user deposits in the form of stablecoins, issue digital dollars, and settle payments 24/7. Lending remains isolated, but custody, compliance, and liquidity have slowly transitioned to the realm of code. We may be entering a new era where a new generation of Stripes will build on these financial primitives.

But does this increase risk? Are we allowing startups to gamble with user deposits, or just allowing suited individuals to do so? Not entirely. Digital dollars or stablecoins tend to be much more transparent than their traditional counterparts. In the traditional world, risk assessment is a private matter. On-chain, it is publicly verifiable. When ETF or DAT holdings can be verified on-chain, we see a version of this situation where you can even verify how much Bitcoin countries like El Salvador or Bhutan hold.

The transformation we will witness is that products may look like Web2, but assets will be on a Web3 track.

If blockchain tracks enable faster fund transfers, and digital primitives like stablecoins allow users to hold deposits under appropriate regulatory regimes, we will see the emergence of a new generation of banks with a radically different unit economics model.

But understanding this transformation first helps to grasp the components that make up a bank.

Building blocks of banks

What exactly are banks? At their core, they do four things:

First, it holds information about who owns how much assets, a database.

Second, it allows people to transfer funds between each other through transfers and payments.

Third, it ensures compliance with users to guarantee that the assets held by banks are legitimate.

Fourth, it uses information in the database to upsell loans, insurance, and trading products.

The way cryptocurrencies are encroaching on these parts is somewhat inverted. For example, stablecoins today are not mature banks, but they possess immense appeal in terms of transaction volume. Visa and Mastercard have historically charged tolls on everyday transactions. Each swipe adds a few basis points to their moat because merchants have no alternative.

By 2011, the average debit card fee in the U.S. was about 44 basis points, high enough for Congress to pass the Durbin Amendment, halving those rates. Europe set its cap lower in 2015, with debit cards at 0.20% and credit cards at 0.30%, after Brussels deemed the two giants as 'coordinated rather than competitive'. However, U.S. credit cards without a cap still settle at rates of 2.1%–2.4% today, slightly lower than a decade ago.

Stablecoins have upended this economic model. On Solana or Base, the settlement cost of a USDC transfer is less than $0.20, a fixed fee regardless of amount. Shopify merchants accepting USDC via self-custodied wallets can retain the 2% credit card network fees that were once charged. Stripe has already caught on. It now offers a 1.5% checkout rate for USDC, down from its 2.9% + $0.30 fee rate.

New ways of moving money in the U.S.

These tracks invite new participants at a much lower cost. YC-backed Slash lets any exporter start accepting payments from U.S. customers in five minutes, without a Delaware C corp, acquiring bank contracts, paperwork, or lawyer retainer fees—just a wallet. The message to traditional processors is direct: upgrade to stablecoins or lose card revenue.

For users, the economic rationale is quite straightforward.

Accepting stablecoins in emerging markets means avoiding the hassle and astonishing fees associated with foreign exchange.

It is also the fastest way to send money across borders, especially for merchants with downstream import payment needs.

You save about 2% in fees that you would need to pay to Visa and Mastercard. There are off-ramping costs, but stablecoins are trading at a premium to the dollar in most emerging markets. USDT is currently trading at 88.43 rupees in India, while the dollar price from Transferwise is 87.51 rupees.

The reason stablecoins are accepted in emerging markets is that the economic rationale is quite direct. It is cheaper, faster, and safer. In regions like Bolivia, where inflation reaches 25%, stablecoins provide a viable alternative to government-issued currency. Essentially, stablecoins give the world a taste of what blockchain as a financial track might look like. The natural evolution will be to explore what other financial primitives these tracks can enable.

Merchants converting cash to stablecoins will soon find that the issue is not receiving funds but operating on-chain. Funds still need to be stored in the vault, yesterday’s flows must be reconciled, vendors expect payment, payroll needs to be streamed, and auditors require proof.

Banks encapsulate all of this in their core banking systems, which are behemoths of the mainframe era, written in Cobol, maintaining ledgers, executing cutoff times, and pushing batch files.

Core banking software (CBS) performs two fundamental tasks:

Maintaining a tamper-proof real ledger: who owns what, mapping accounts to customers.

Safely making that ledger public: supporting payments, loans, cards, reporting, and risk management.

Banks outsource this work to CBS software providers. These providers are tech companies skilled in software, while banks excel in finance. This architecture originates from the computerization of the 1970s, when branches transitioned from paper ledgers to connected data centers, then became rigid under a mountain of regulations.

The FFIEC is an organization that publishes operational regulations for all U.S. banks. It outlines the rules core banking software should follow: placing primary and backup data centers in different geographic regions, maintaining redundant telecommunications lines and power, continuously logging transaction records, and continuously monitoring any security incidents.

Replacing core banking systems is a top-tier defensive event because data, every customer balance and transaction, is trapped in the vendor’s database. Migration means weekend switches, dual ledger operations, regulatory fire drills, and a high likelihood of failure the next morning. This inherent stickiness turns core banking into a near-permanent lease. The top three vendors, Fidelity Information Services (FIS), Fiserv, and Jack Henry, trace back to the 1970s and still lock banks into contracts lasting about seventeen years. They collectively serve over 70% of banks and nearly half of credit unions.

Pricing is usage-based: a retail checking account costs between $3 and $8 per month, decreasing as volume increases but increasing with additional features like mobile banking. Activating fraud tools, FedNow payment tracks, and analytics dashboards will raise fees even higher.

Fiserv alone generated $20 billion in revenue from banks in 2024, about 10 times the fees on the Ethereum chain during the same period.

Placing the assets themselves on a public chain means that the data layer is no longer proprietary. USDC balances, tokenized treasury bonds, and loan NFTs all reside on the same open ledger, which any system can read. If a consumer application believes its current 'core layer' is too slow or too expensive, it does not need to migrate bytes of state; it merely directs a new orchestration engine to the same wallet address and continues to operate.

That said, the cost of switching won't drop to zero; it will just mutate. Payroll providers, ERP systems, analytics dashboards, and audit pipelines will all need to integrate with the new core. Switching vendors means reconnecting those hooks, which is no different from switching cloud providers. The core is not just a ledger; it also runs business logic: mapping user accounts, cutoff times, approval workflows, and exception handling. Even if balances are portable, recoding that logic in a new tech stack still requires effort.

The difference is that these frictions are now software issues rather than data hostage issues. There are still glue work to code workflows, but those are sprint cycle issues rather than years of hostage negotiations. Developers can even adopt a multi-core strategy, one engine for retail wallets and another for treasury operations, as both point to the same authoritative blockchain state. If a vendor has issues, they failover by redeploying containers rather than orchestrating data migrations.

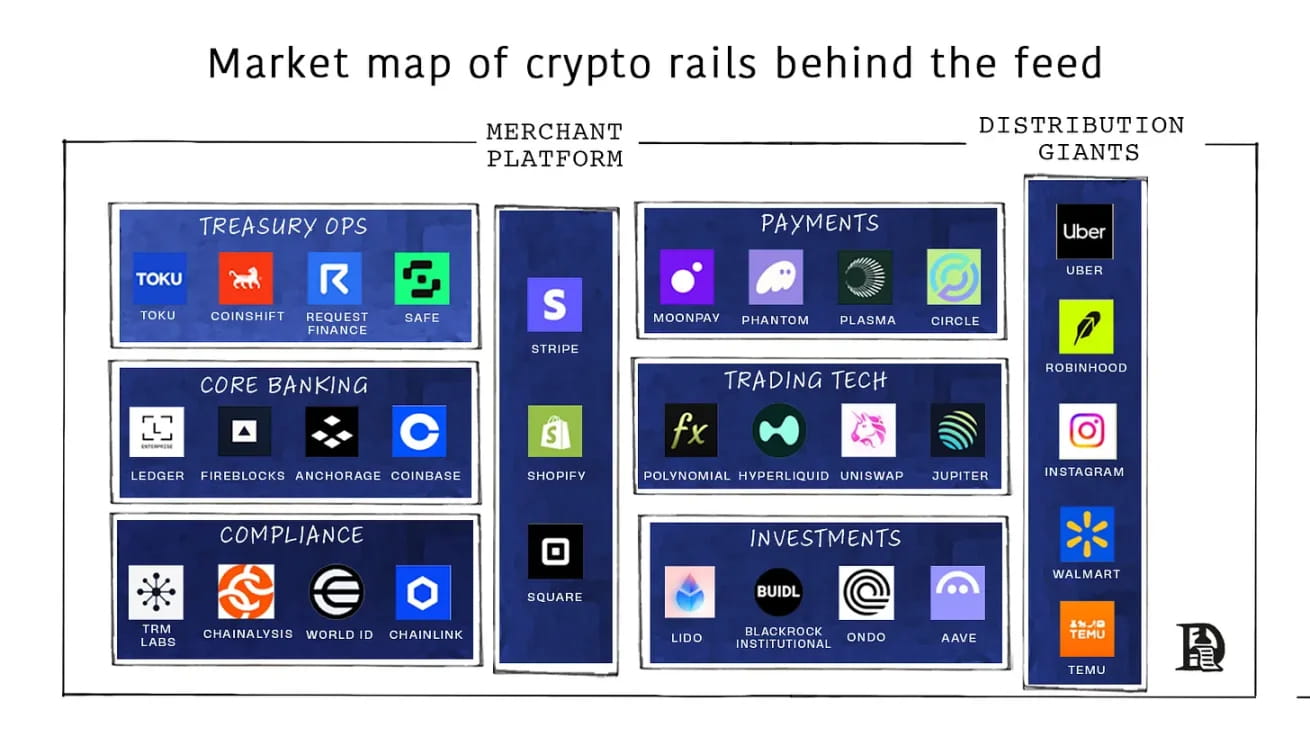

Viewing the future of banking through these lenses may look very different. These components exist in isolation today, waiting for developers to package them together for retail users.

Fireblocks protects over $10 trillion in token flows for banks like BNY Mellon. Its strategy engine can mint, route, stake, and verify stablecoins across more than 80 chains.

Safe protects approximately $100 billion in smart account treasuries; its SDK provides any application with simple login, multi-signature policies, gas abstraction, streaming payroll, and automatic rebalancing.

Anchorage Digital, the first chartered cryptocurrency bank, rents out a regulated balance sheet that understands Solidity language. Franklin Templeton directly mints its Benji Treasury Fund into Anchorage custody and settles shares on T+0 instead of T+2.

Coinbase Cloud provides wallet issuance, MPC custody, and sanctioned transfer checks as a single API.

These participants possess elements that traditional vendors lack: an understanding of on-chain assets, compliance anti-money laundering baked into the protocol, and event-driven APIs rather than batch files. Compare this with a market expected to grow from about $17 billion today to about $65 billion by 2032, and the equation is simple: items that once belonged to Fidelity and its partners are now up for grabs, and companies delivering products in Rust and Solidity rather than Cobol will seize it.

But before they are truly ready for retail, they need to battle the great evil that all financial products must confront: compliance. What might compliance look like in an increasingly on-chain world?

Code is compliance

Banks run four types of compliance: know your customer (KYC and due diligence), screening counterparties (sanctions and PEP checks), monitoring funds (transaction monitoring with alerts and investigations), and reporting to regulators (SARs/CTRs, audits). This is huge, costly, and ongoing. In 2023, global spending exceeded $274 billion, and the burden is increasing almost every year.

The scale of paperwork exposes risk patterns. FinCEN reported approximately 4.7 million suspicious activity reports and 20.5 million currency transaction reports last year, all of which are retrospective forms about risk. This work is bulk-intensive: collecting PDFs and logs, compiling narratives, submitting reports, and waiting.

For on-chain transactions, compliance is no longer a bunch of manual artifacts but begins to operate like a real-time system. The FATF's 'travel rule' requires sender/beneficiary information to be transmitted with transfers; cryptocurrency providers must acquire, hold, and transmit this data (traditionally above a $1,000 threshold for 'occasional transactions'). The EU has gone further, applying this rule to all cryptocurrency transactions. On-chain, this payload can be transmitted as a cryptographic data block along with the transfer for regulators to use but is not visible to the public. Chainlink and TRM release sanctions lists and fraud oracles; transfers query the list during the process and will roll back if the address is flagged.

Once zero-knowledge wallets like Polygon ID or World ID can carry a cryptographic badge to prove, for instance, 'I am over 18 and not on any sanctions list', privacy is also preserved. Merchants see the green light, regulators gain an auditable trail, and users never have to disclose passport scans or street addresses.

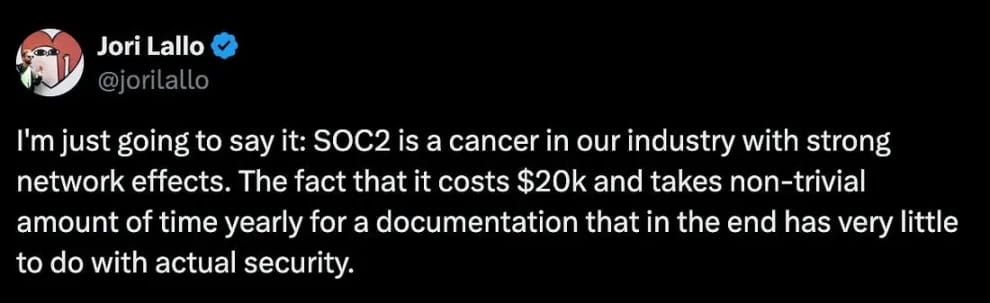

If funds are stuck in back-office paperwork, a fast, liquid market is of no use. Vanta is an example of a reg-tech startup that moved SOC2 compliance from consultants and screenshots to an API. Startups selling software to Fortune 500 companies need a SOC2 certificate. This should demonstrate that you adhere to reasonable security practices and avoid storing customer data in unprotected public links.

Startups need to hire auditors who bring in a massive spreadsheet asking for all screenshots from AWS setups to Jira tickets, disappear for six months, and then return with an expiring signed PDF. Vanta simplifies this ordeal into an API. You don’t need to hire consultants; instead, connect Vanta to your AWS, GitHub, and HR tech stack; it monitors logs, automatically takes the same screenshots, and provides them to auditors. This has propelled Vanta to $200 million in annual recurring revenue (ARR) and a valuation of $4 billion.

The founder of Linear laments the state of compliance.

Finance will follow the same trajectory: less binder management, more strategy engines evaluating events in real-time, and then leaving behind cryptographic receipts. Balances and liquidity are transparent, timestamped, and cryptographically signed, making auditing an observation.

Oracles like Chainlink act as trusted facilitators between off-chain rulebooks and on-chain executions. Its proof-of-reserve data flows make reserve adequacy clearly readable to contracts, enabling publishers and venues to connect to automatically responding circuit breakers. There’s no need to wait for annual audits; the ledger is continuously monitored.

Proof of reserves gradually reaches the level of liquid collateral; if a stablecoin's collateralization ratio falls below 100%, the minting function automatically locks and notifies regulators.

There is still real work to be done. Identity verification, cross-jurisdictional rules, edge case investigations, and machine-readable policies all need to be strengthened. The next few years will feel less like dealing with paperwork and more like conducting API version control: regulators release machine-readable rules, oracle networks and compliance vendors provide reference adapters, and auditors shift from sampling to oversight. As regulators understand what real-time auditing can bring, they will collaborate with vendors to implement a new class of tools.

A new era of trust

Everything gets bundled, then steadily unbundled. The human story is about constantly trying to improve efficiency by integrating things together, only to realize decades later that they are better off remaining independent. (The legislative nature around stablecoins) and the state of the underlying networks (Arbitrum, Solana, Optimism) means we will see repeated attempts to rebuild banks. Yesterday, Stripe announced its attempt to launch an L1.

Two forces are at play in modern society.

Due to inflation leading to rising costs.

Due to our highly interconnected world, meme desires are rising.

In an era where people's desires to consume are increasing while wages stagnate, more people will take control of their finances. The GameStop surge, the rise of meme coins, and the frenzy around Labubu or the Stanley Cup are all effects of this shift. This means that applications with enough distribution capability and embedded trust will evolve into banks. What we will see is the version of the Hyperliquid builders code system extending across the entire financial world. Whoever owns the distribution channels will ultimately become the bank.

If your most trusted influencer recommends a portfolio on Instagram, why would you trust JPMorgan? If you can trade directly on Twitter, why bother trading on Robinhood? What about me? Personally? My preferred way to lose money would be to store it on Goodreads to buy rare books. My point is, with the advent of the (GENIUS Act), legislation allowing products to hold user deposits has changed. In a world where the mobile components that constitute a bank turn into API calls, more products will mimic banks.

Platforms that own the information flow will be the first to undergo this transformation, which is not a new phenomenon. Social networks relied heavily on e-commerce platform activities to monetize early on, as that was where money changed hands. Users seeing ads on Facebook might purchase products on Amazon, generating referral revenue for Facebook. In 2008, Amazon launched an app called Beacon to specifically view platform activity to create wish lists. Throughout the history of the web, there has been a beautiful waltz between attention and commerce. Embedding banking infrastructure into their platforms will be another mechanism closer to where the money resides.

Won’t legacy firms jump on this trend of providing access to digital assets? Existing fintech companies won’t just sit by, right? FIS is negotiating with virtually every bank, knowing what’s happening. Ben Thompson's point in his recent article is simple and brutal: when the paradigm flips, yesterday's winners find themselves at a disadvantage because they want to continue doing what they did to win. They optimize for the old game, defend outdated KPIs, and make the right decisions for the wrong world. This is the curse of the winner, and it equally applies to money on-chain.

When everything is a bank, nothing is a bank. If users do not trust a single platform to host most of their wealth, the place for fund storage will become fragmented. This has already happened for crypto-native users who store most of their wealth on exchanges rather than banks. This means the unit economics of bank revenue will change. Smaller applications may not need as much revenue to operate as large banks do, because much of their business may occur without human intervention. But this means that traditional banks as we know them will slowly fade away.

Perhaps like life, technology is merely a continuum of creation and destruction, bundling and unbundling.