"The balance of risks is shifting." When Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell uttered these words at Jackson Hole, global financial markets instantly tensed. This was Powell's final address at the annual gathering of global central banks during his tenure, and it presented him with the most complex policy environment yet. With inflation resurfacing, job growth slowing sharply, and the new administration's tariff policies pushing up prices, the Fed stood at an unprecedented crossroads.

The data is shocking. Job growth plummeted to an average of 35,000 per month in July, just one-fifth of the 2024 target. Core inflation climbed to 2.9%, far exceeding the Fed's 2% target. Tariffs are starting to take effect, with commodity prices rising by 1.1%. Behind these figures lies the profound changes the US economy is undergoing. Even more worrying is that Powell publicly acknowledged for the first time a "challenging situation"—upward inflation risks and downward employment risks.

This dual pressure creates a dilemma for traditional monetary policy tools: raising interest rates could further undermine employment, while lowering them could drive up inflation. Powell's statement, "We will never allow a one-time increase in prices to become a persistent inflationary problem," served as both a promise to the market and a glimpse into the Fed's internal anxieties.

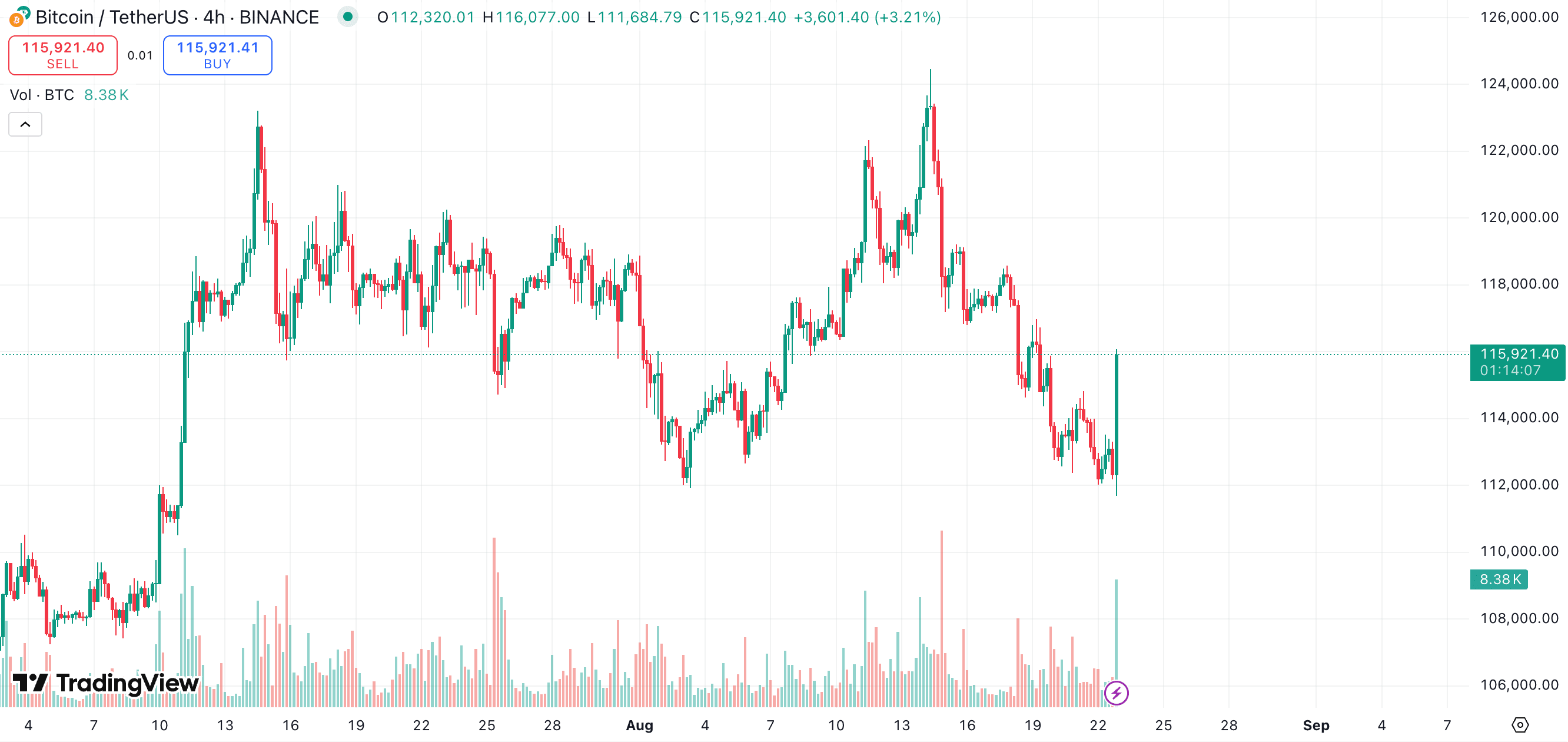

For the crypto market, these macro signals are far more than just background noise. Over the past two years, digital asset price fluctuations have been highly dependent on the tightness of US dollar liquidity and the direction of US Treasury yields. Powell's statement that "the balance of risks is shifting" suggests that the liquidity environment on which the crypto market depends is reaching a turning point. With limited room for interest rate hikes and inflationary constraints on rate cuts, the market is beginning to realize that uncertainty itself is the new certainty.

In what has been dubbed his "farewell speech," Powell also announced a major overhaul of the Federal Reserve's monetary policy framework—the first revision since 2020. The new framework emphasizes the "inclusiveness" of employment targets, providing greater flexibility for policy adjustments. However, even the most flexible framework struggles to provide ready-made answers in the face of the current complexities. For the more speculative crypto assets, this means that market narratives and risk appetite will fluctuate more dramatically than ever before.

The looming threat of tariffs is reshaping the US economy. Powell admitted that "significantly higher tariffs are reshaping the global trading system," and that their impact on consumer prices is "now clearly visible." This isn't just a description of economic reality; it's a warning to policymakers: monetary policy must strike a balance between political pressure and economic principles. For the crypto market, it's also a reminder that every swing in macroeconomic policy quickly reflects on the capital flows and valuations of risky assets.

The market is holding its breath awaiting the Federal Reserve's next move. Expectations for a September rate cut remain strong, but Powell's speech suggests that this decision will be more difficult than ever. Caught between inflation and employment, the Fed is forging an uncharted path. As global capital seeks hedging and safe havens, crypto assets may also find a new role in this uncharted path.

The following is the full text of the speech:

The U.S. economy has demonstrated resilience this year amidst widespread economic policy changes. The labor market remains near full employment, a measure of the Federal Reserve's dual mandate, and inflation, while still somewhat elevated, has retreated significantly from its post-pandemic peak. At the same time, the balance of risks appears to be shifting.

In my remarks today, I will first discuss the current economic situation and the near-term outlook for monetary policy. I will then turn to the findings of our second public review of our monetary policy framework, as reflected in the revised Statement on Longer-Run Goals and Monetary Policy Strategy, which we released today.

Current Economic Conditions and Near-Term Outlook

When I took this podium a year ago, the economy was at a turning point. Our policy interest rate had been maintained at 5.25% to 5.5% for over a year. This restrictive policy stance was appropriate, helping to lower inflation and promote a sustainable balance between aggregate demand and aggregate supply. Inflation was very close to our objective, and the labor market had cooled from its previous overheating. Upward risks to inflation had diminished. However, the unemployment rate had risen by nearly a full percentage point, a level unprecedented in history except during a recession. Over the three subsequent Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) meetings, we recalibrated our policy stance, laying the foundation for a labor market that has remained balanced near full employment over the past year (Figure 1).

This year, the economy faces new challenges. Significant tariff increases among our trading partners are reshaping the global trading system. Tighter immigration policies have led to a sudden slowdown in labor force growth. Longer-term, changes in tax, spending, and regulatory policies are also likely to have important implications for economic growth and productivity. There is significant uncertainty about the ultimate trajectory of all these policies and what their lasting impact on the economy will be.

Changes in trade and immigration policies are affecting both demand and supply. In this environment, distinguishing cyclical from trend-based (or structural) developments is difficult. This distinction is crucial because monetary policy can try to stabilize cyclical fluctuations but cannot address structural changes.

The labor market provides a good example. The July jobs report released earlier this month showed that job creation slowed to an average of just 35,000 per month over the past three months, down from 168,000 per month projected through 2024 (Figure 2). This slowdown was much larger than estimated just a month ago, as earlier data for May and June were revised down significantly. However, it does not appear to have resulted in the significant slack in the labor market that we would have preferred to avoid. The unemployment rate, while rising slightly in July, remains at a historically low 4.2% and has remained largely stable over the past year. Other indicators of labor market conditions have also shown little change or only moderate weakness, including quits, layoffs, the ratio of job openings to unemployed persons, and nominal wage growth. The simultaneous weakening of labor supply and demand has significantly reduced the "break-even" rate of job creation required to maintain a constant unemployment rate. Indeed, with the sharp decline in immigration, labor force growth has already slowed significantly this year, and the labor force participation rate has declined in recent months.

Overall, while the labor market appears to be in equilibrium, this is an unusual equilibrium caused by a significant slowdown in both labor supply and demand. This unusual situation suggests that downside risks to employment are rising. If these risks materialize, they could quickly manifest themselves in the form of a sharp increase in layoffs and a rise in the unemployment rate.

Meanwhile, GDP growth slowed significantly in the first half of this year, to 1.2%, roughly half the 2.5% rate projected for 2024 (Figure 3). The decline in growth primarily reflects a slowdown in consumer spending. As with the labor market, some of the GDP slowdown likely reflects slower supply or potential output growth.

Turning to inflation, higher tariffs have begun to push up prices in some categories of goods. Estimates based on the latest available data suggest that overall PCE prices rose 2.6% in the 12 months ending in July. Excluding the volatile food and energy categories, core PCE prices rose 2.9%, higher than a year ago. Within core inflation, goods prices rose 1.1% over the past 12 months, a notable turnaround from the modest decline seen during 2024. By contrast, housing services inflation remains on a downward trend, while non-housing services inflation remains slightly above levels historically consistent with 2% inflation (Figure 4).

The impact of tariffs on consumer prices is now clearly visible. We expect these effects to accumulate over the coming months, but their timing and magnitude are highly uncertain. The important question for monetary policy is whether these price increases are likely to materially increase the risk of persistent inflation problems. A reasonable baseline scenario is that the impact will be relatively short-lived—a one-time shift in the price level. Of course, "one-time" does not mean "all at once." Tariff increases take time to be transmitted throughout supply chains and distribution networks. Moreover, tariff rates are still evolving, which could prolong the adjustment process.

However, there is also the risk that upward price pressures from tariffs could trigger more persistent inflationary dynamics, a risk that needs to be assessed and managed. One possibility is that workers, whose real incomes have fallen due to rising prices, could demand and obtain higher wages from their employers, triggering adverse wage-price dynamics. This outcome seems unlikely given that the labor market is not particularly tight and faces increasing downside risks.

Another possibility is that inflation expectations could rise, pulling actual inflation higher with them. Inflation has been above our objective for more than four consecutive years and remains a prominent concern for households and businesses. However, judging by market-based and survey-based indicators, longer-term inflation expectations appear well anchored and consistent with our 2% longer-run inflation objective.

Of course, we cannot assume that inflation expectations will remain stable. Whatever happens, we will not allow a one-time increase in the price level to become a persistent inflation problem.

Taken together, what are the implications for monetary policy? In the near term, risks to inflation are tilted to the upside, while risks to employment are tilted to the downside—a challenging situation. When our objectives are in tension like this, our framework requires us to balance the two sides of our dual mandate. Our policy rate is now 100 basis points closer to neutral than it was a year ago, and the stability of the unemployment rate and other labor market indicators allows us to proceed cautiously when considering changes to the stance of policy. Nevertheless, with policy in restrictive territory, the baseline outlook and the evolving balance of risks may require adjustments to the stance of policy.

There is no preset path for monetary policy. Members of the Federal Open Market Committee will make these decisions solely based on their assessment of the data and its implications for the economic outlook and the balance of risks. We will never deviate from this approach.

Evolution of the monetary policy framework

Turning to my second topic, our monetary policy framework is based on the unchanging mandate given to us by Congress to promote maximum employment and stable prices for the American people. We remain fully committed to our statutory mandate, and the revisions to our framework will support that mandate under a wide range of economic conditions. Our revised Statement on Longer-Run Goals and Monetary Policy Strategy, which we call the Consensus Statement, describes how we pursue our dual-mandate objectives. It is intended to provide the public with a clear understanding of how we think about monetary policy, an understanding that is essential for transparency and accountability, and for making monetary policy more effective.

The changes we've made in this review are a natural evolution, rooted in our deepening understanding of the economy. We continue to build on the original consensus statement adopted in 2012 under Chairman Ben Bernanke. Today's revised statement is the product of the second public review of our framework, which we conduct every five years. This year's review includes three elements: Fed Listens events held at Reserve Banks nationwide, a flagship research conference, and discussions and deliberations among policymakers at a series of FOMC meetings, supported by staff analysis.

In conducting this year's review, a key goal was to ensure that our framework is applicable across a wide range of economic conditions. At the same time, the framework needs to evolve as the structure of the economy and our understanding of those changes change. The challenges posed by the Great Depression differed from those during the Great Inflation and the Great Moderation, which in turn differed from the challenges we face today.

At the time of our last review, we were living in a new normal characterized by interest rates near the effective lower bound (ELB), accompanied by low growth, low inflation, and a very flat Phillips curve—meaning that inflation was unresponsive to slack in the economy. To me, a statistic that captures that era is that our policy rate remained at the ELB for seven years, starting in late 2008, following the onset of the Global Financial Crisis (GFC). Many of you will remember the pain of weak growth and a very slow recovery during that era. It seemed highly likely that, even in the event of a mild recession, our policy rate would quickly return to the ELB and potentially remain there for an extended period. Inflation and inflation expectations would then likely decline in a weak economy, pushing up real interest rates with nominal interest rates pegged near zero. Higher real interest rates would further depress employment growth and exacerbate downward pressure on inflation and inflation expectations, triggering an unfavorable dynamic.

The economic conditions that pushed the policy rate to the effective lower bound and prompted the 2020 framework changes were viewed as rooted in slow-moving global factors that would persist for a long time—and they would likely have been so had it not been for the pandemic. The 2020 Consensus Statement included several features that addressed the risks associated with the effective lower bound that have grown in prominence over the past two decades. We emphasized the importance of anchoring long-term inflation expectations in supporting our dual objectives of price stability and maximum employment. Drawing on the extensive literature on strategies to mitigate risks associated with the effective lower bound, we adopted a flexible form of average inflation targeting—a "make-up" strategy to ensure that inflation expectations remain well anchored even under the constraints of the effective lower bound. Specifically, we stated that after periods of sustained inflation below 2 percent, appropriate monetary policy might aim to achieve inflation moderately above 2 percent for some time.

As a result, the post-pandemic reopening resulted not in low inflation and an effective lower bound on interest rates, but rather in the highest inflation the global economy had seen in 40 years. Like most other central bankers and private sector analysts, until the end of 2021, we assumed that inflation would recede fairly quickly without a significant tightening of our policy stance (Figure 5). When it became clear that this was not the case, we responded forcefully, raising our policy rate by 5.25 percentage points over 16 months. This action, combined with the easing of supply disruptions during the pandemic, has brought inflation closer to our objective without the painful rise in unemployment that accompanied previous efforts to combat high inflation.

Elements of the revised consensus statement

This year's review considers the evolution of economic conditions over the past five years. During this period, we have seen how quickly inflation can shift in the face of large shocks. Moreover, interest rates are now much higher than they were between the global financial crisis and the pandemic. With inflation above target, our policy rate is restrictive—in my view, mildly restrictive. We cannot be certain where interest rates will stabilize over the long term, but their neutral level is likely higher now than it was in the 2010s, reflecting changes in productivity, demographics, fiscal policy, and other factors affecting the balance between saving and investment (Figure 6). During the review, we discussed how the 2020 statement's focus on the effective lower bound on interest rates might have complicated the communication of our response to high inflation. We concluded that the emphasis on an overly specific set of economic conditions may have led to some confusion, and we have therefore made several important revisions to the consensus statement to reflect this insight.

First, we removed language suggesting that the effective lower bound is a defining feature of the economic landscape. Instead, we stated that our "monetary policy strategy is designed to foster maximum employment and stable prices under a wide range of economic conditions." Difficulties operating near the effective lower bound remain a potential concern, but it is not our primary focus. The revised statement reiterates the Committee's readiness to use its full range of tools to achieve its maximum employment and price stability goals, particularly if the federal funds rate is constrained by the effective lower bound.

Second, we returned to a flexible inflation targeting framework and eliminated the "catch-up" strategy. The idea that a modest overshoot in inflation was intentional has proven irrelevant. The inflation that arrived in the months following our announcement of the revised 2020 Consensus Statement was neither intended nor appropriate, as I publicly acknowledged in 2021.

Well-anchored inflation expectations are crucial to our success in reducing inflation without causing a sharp rise in unemployment. They help return inflation to target when adverse shocks push it higher and limit deflationary risks during periods of economic weakness. Furthermore, they allow monetary policy to support maximum employment during recessions without compromising price stability. Our revised statement emphasizes our commitment to taking forceful action to ensure that longer-term inflation expectations remain well-anchored, serving both prongs of our dual mandate. It also states that "price stability is fundamental to a sound and stable economy and supports the well-being of all Americans." This theme came through loud and clear in our "Fed Listens" events. The past five years have been a painful reminder of the hardships that high inflation imposes, especially on those least able to afford the higher costs of essential goods.

Third, our 2020 statement stated that we would aim to mitigate "shortfalls," not "deviations," from full employment. The use of the term "shortfalls" reflects the recognition that our real-time assessment of the natural rate of unemployment—and, by implication, "full employment"—is highly uncertain. In the late stages of the recovery from the global financial crisis, employment remained above mainstream estimates of its sustainable level for extended periods, while inflation ran persistently below our 2% objective. In the absence of inflationary pressures, tightening policy based solely on uncertain real-time estimates of the natural rate of unemployment may not be warranted.

We still hold this view, but our use of the word "inadequate" has not always been interpreted as intended, creating communication challenges. In particular, the use of the word "inadequate" was not intended to be a commitment to permanently abandon preemptive action or to ignore tight labor markets. Therefore, we have removed the word "inadequate" from the statement. Instead, the revised document now more precisely states, "The Committee recognizes that employment may at times be above the real-time assessment of full employment without necessarily posing risks to price stability." Of course, preemptive action may be necessary if tight labor markets or other factors pose risks to price stability.

The revised statement also states that full employment is "the highest level of employment that can be sustainably achieved in an environment of price stability." This focus on promoting a strong labor market emphasizes the principle that "durable full employment leads to broad-based economic opportunities and benefits for all Americans." The feedback we received during the "Fed Listens" event reinforced the value of a strong labor market for American families, employers, and communities.

Fourth, consistent with the removal of the word "fall short," we have made revisions to clarify our approach during periods when our employment and inflation objectives are not complementary. In these cases, we will take a balanced approach to promoting them. The revised statement is now more consistent with the original 2012 wording. We will consider the extent of deviations from our objectives and the potentially different timeframes over which we expect each objective to return to levels consistent with our dual mandate. These principles guide our policy decisions today, just as they will guide us during the 2022-24 period, when deviations from our 2% inflation objective are of overriding concern.

Despite these changes, there is significant continuity with past statements. The document continues to explain how we interpret the mandate given to us by Congress and describes the policy framework we believe will best promote maximum employment and price stability. We continue to believe that monetary policy must be forward-looking and account for the time lags of its effects on the economy. Therefore, our policy actions depend on the economic outlook and the balance of risks to that outlook. We continue to believe that it is unwise to set a numerical target for employment because the level of full employment cannot be measured directly and varies over time for reasons unrelated to monetary policy.

We also continue to believe that a 2% inflation rate over the longer term is most consistent with our dual mandate. We believe our commitment to this target is a key factor in helping to keep longer-term inflation expectations well anchored. Experience has shown that a 2% inflation rate is low enough to ensure that inflation does not become a concern in the decision-making of households and businesses, while also providing some flexibility for the central bank to provide policy accommodation during a recession.

Finally, the revised consensus statement retains our commitment to conduct public reviews approximately every five years. There's nothing magical about this five-year cadence. This frequency allows policymakers to reassess the structural characteristics of the economy and engage with the public, practitioners, and academics on the performance of our framework. It is also consistent with the practices of several global peers.

in conclusion

Finally, I want to thank Chairman Schmid and his entire staff for their hard work in putting on this outstanding event each year. Including several virtual appearances during the pandemic, this marks my eighth time having had the honor of speaking from this podium. Each year, this symposium provides the leadership of the Federal Reserve with an opportunity to hear from leading economic thinkers and focus on the challenges we face. Over forty years ago, the Kansas City Fed made a wise move by attracting Chairman Volcker to this national park, and I am proud to be a part of that tradition.