Author|Felix Ng

Compiled by Wu Says Blockchain Aki Chen

The full text is as follows:

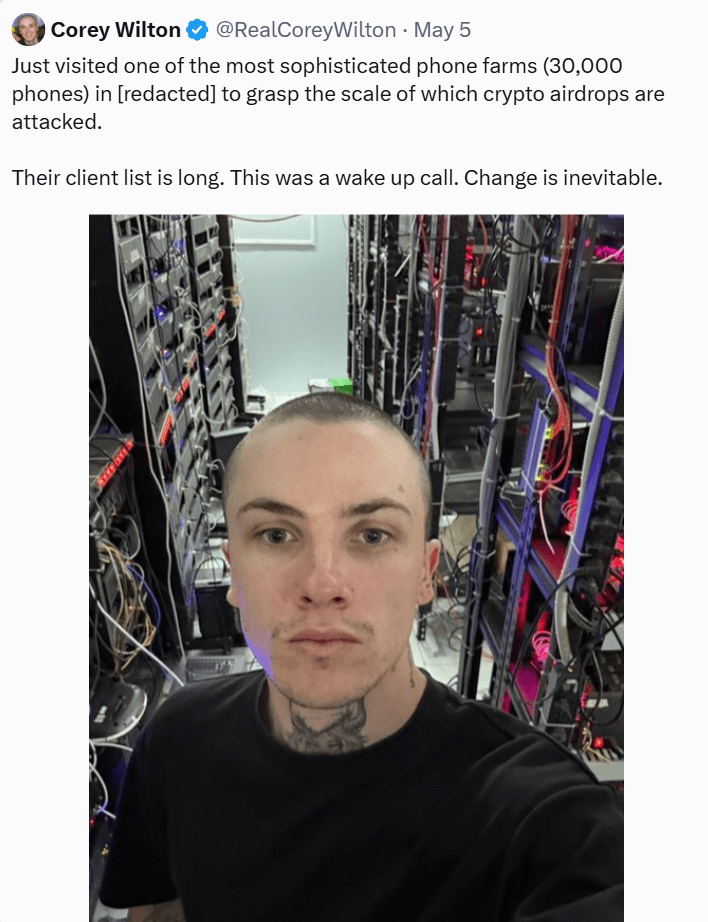

In a 'tin shed' with a cold storage system just 40 minutes from Ho Chi Minh City, Mirai Labs CEO Corey Wilton first truly realized the enormous scale of crypto airdrop abuse. 'It's really chilling,' Wilton said in an interview. He had just visited a 'phone farm' in southern Vietnam, where he estimated that the space, only the size of a studio apartment, housed at least 30,000 smartphones.

For the past four years, Wilton has hoped to witness firsthand the operational model behind the NFT racing game Pegaxy, which collapsed in 2021. "At that time, Pegaxy was booming, and our daily active user count peaked at about 500,000," Wilton recalled. "We began receiving numerous reports about 'robot farms.'" These robots could control hundreds of accounts simultaneously, quickly purchasing racehorses with higher win rates and repeatedly participating in races to earn in-game currency, which could then be converted into real-world value. "You would see screenshots from users with dozens of applications running on their screens, and similar scenes frequently appear on social media," he explained.

Pegaxy is an auto-running horse racing game featuring fifteen horses competing simultaneously. Wilton stated that the robot farm transformed the game from 'who can win' into 'who can extract value faster' — thus changing the game's atmosphere and accelerating the project's decline.

On-site: Revealing Vietnam's 'professional' phone farms

In May this year, Wilton finally got his wish, gaining exclusive access to a 'highly specialized phone farm' in Vietnam with the help of a former Pegaxy player. This player stumbled upon the traces of this farm on TikTok.

"I went to two places, both about 40 minutes from where I was, relatively remote areas," he recalled. "There definitely wouldn't be any foreigners there, and they completely do not want to be known." Wilton described one of the locations as a tin shed right next to the street, with the air conditioning set to 'as cold as it can get.'

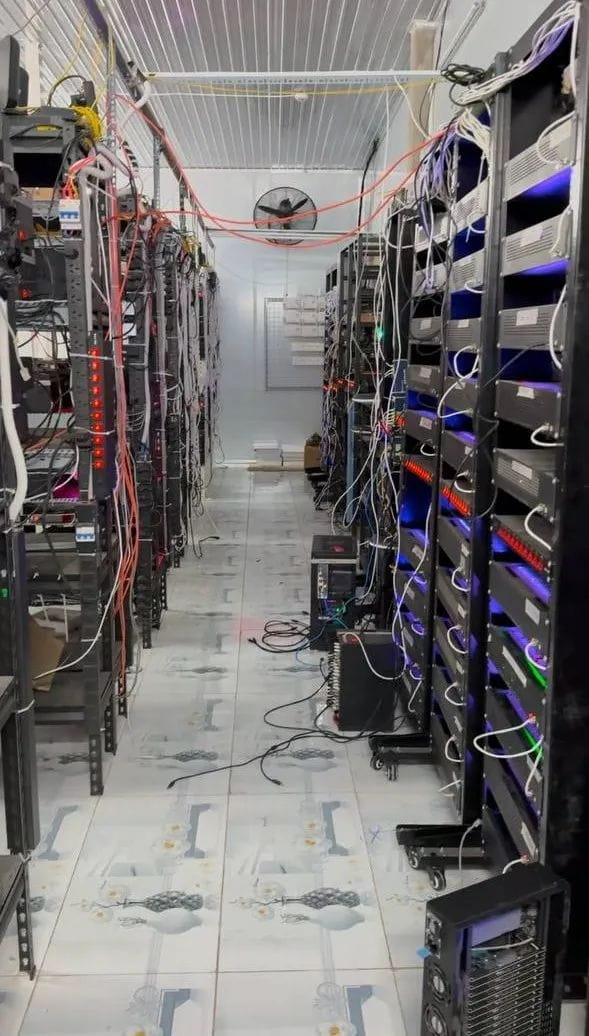

Inside the tin shed, metal racks were filled with thousands of smartphones, leaving only narrow aisles for employees to pass through. The entire layout looked like a 'sham' crypto mining farm.

Wilton stated that the other party showed him the 'leasing segment' of the business, where clients can rent this phone farm for any purpose based on their needs. Unlike traditional robot servers, each device in the phone farm is equipped with its own SIM card and device fingerprint, and can also disguise its IP geographical location, making it more difficult to detect, especially suitable for systems that require each account to bind a mobile number. Additionally, phones offer a high cost-performance ratio between computing power and cost, and even if one of the devices is damaged, it can be quickly replaced without significantly impacting overall operations.

Wilton mentioned that in the cases he witnessed, an operator would control a 'master control phone' via a computer, which was connected to more than 500 'slave phones.' No matter what operation was executed on the master control phone, all slave devices would synchronize and replicate. 'Most of their clients actually come from the Web2 industry. For instance, a K-pop agency rents these devices to boost traffic; there are also casinos using it to simulate real players, making the game appear more 'real,' but in fact, it's used to suppress you and lead you to lose money.'

"Some Web2 players are batch farming mobile games by nurturing accounts and then selling these upgraded accounts," he added. However, Wilton indicated that the core business of this farm is actually 'manufacturing.'

The operator would buy damaged or old smartphones at low prices, then modify them through software and other means, ultimately packaging them into 'self-service phone farm' devices for sale in overseas markets. This project can produce over 1,000 deployable farm phones each week, with each 'phone farm kit' containing about 20 devices. Wilton noted that these individuals do not operate the phones themselves. They do not fleece airdrops or execute related operations. Their main business is actually packaging and selling these devices to people overseas who want to operate them from home. Next, you just need to keep these devices online and buy more phones to connect.

Wilton exclaimed that it is no wonder that 'robot-assisted crypto airdrop exploitation' has become a major chronic issue in the crypto industry. The so-called crypto airdrop exploitation refers to acquiring free tokens that should reward genuine early users by creating numerous wallet addresses and fabricating user behaviors. Although most crypto airdrops do not require mobile number verification, the unique device fingerprint and IP address can still bypass the anti-Sybil attack mechanism.

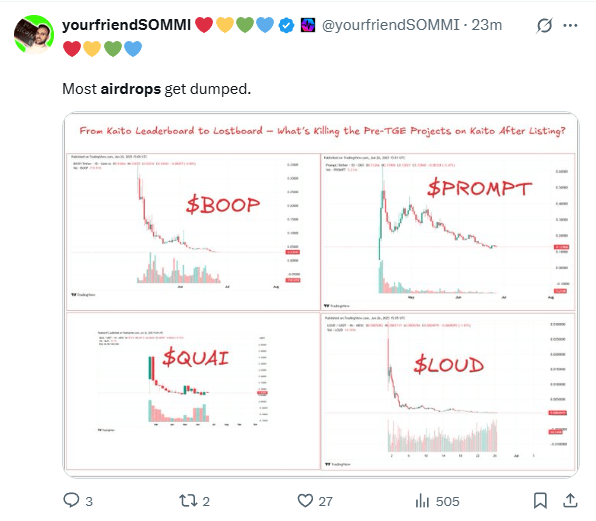

Such practices of 'fleece the airdrop' often lead farm users to immediately sell tokens after receiving them, impacting market prices and making it more difficult for genuine users to obtain airdrops. Many projects experience a surge of fake active behaviors before the airdrop, and once the airdrop is completed, the number of users and the token price often plummet rapidly.

Crypto airdrop controversies are frequent, with robot behavior facing widespread criticism.

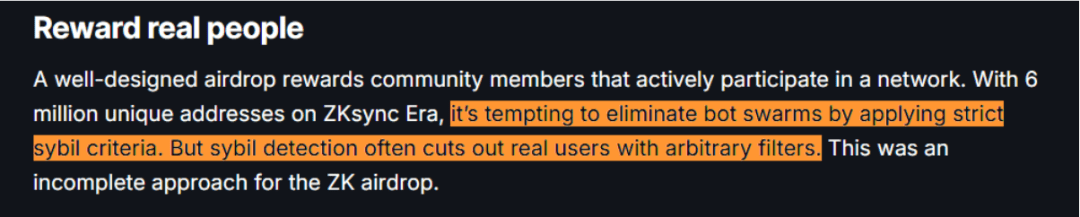

Whether controlled by a large number of mobile phones or a single computer, the behavior of robots has caused significant disruption to crypto airdrop activities. In June last year, the Ethereum zero-knowledge (ZK) Layer2 scaling project ZKsync was heavily criticized for suffering from a large number of robot attacks during its airdrop, with users accusing it of being a convenient gateway for 'robots to fleece the system.'

On-chain data analysis platform Lookonchain reported that an 'airdrop hunter' received over 3 million ZKsync (ZK) tokens through 85 wallet addresses, with a total value of up to $753,000 at the time. Another user boasted on social media that he profited nearly $800,000 through an 'extremely efficient $ZK Sybil attack strategy.'

A so-called 'Sybil attack' is a type of security threat in which an attacker tries to gain an unfair advantage in a network system by creating multiple false identities. The term originates from a book titled 'Sybil,' which describes a woman with multiple personality disorder. Mudit Gupta, security chief of Polygon, ZKsync's competitor, referred to it as 'possibly the easiest airdrop to fleece ever, and also the most over-fleeced,' attributing the problem to the lack of anti-robot mechanisms. Although ZKsync has set seven qualification criteria this time to prevent Sybil attacks.

ZKsync responded in its official FAQ that current Sybil attack strategies are becoming increasingly complex, making it difficult to distinguish them from real users; and while overly strict screening criteria may block some Sybil attackers, they might also mistakenly harm many real users.

However, just last month, Binance expressed a different viewpoint when addressing robot behavior in its 'Binance Alpha Points' program. 'Traditional robots usually follow predictable, repetitive behavior patterns, making them relatively easy to identify,' a Binance spokesperson said in an interview. 'But with the rise of AI-driven robots, we are now faced with a system that closely mimics human behavior — from browsing habits to interaction times, all highly simulating real humans, making identification much more difficult.' Binance stated that the platform is continually increasing its anti-robot efforts, developing new tools to identify abnormal operations from large-scale behavior patterns. For example, address entity association analysis can help identify wallet clusters controlled by the same entity, even if these wallets appear independent on the surface.

These analyses are crucial for revealing behaviors such as disguised holdings, multisend manipulation, and wash trading — tactics commonly used by AI-driven robots to fabricate real engagement and false liquidity. The repercussions extend beyond crypto airdrops, as robots have also been accused of flooding the market, creating countless worthless meme coins. Conor Grogan, Coinbase's product head, recently pointed out on the X platform: 'Most tokens launched on PumpFun and LetsBonk platforms are almost entirely controlled by robots.' He found that on the meme coin platform LetsBonk, top accounts publish a new token on average every three minutes.

Daren Matsuoka, data scientist and partner at a16z Crypto, believes that Sybil attacks are a problem that has only emerged in recent years. "Throughout most of the development history of cryptocurrency, we naturally had a certain resistance to Sybil attacks — because on these Layer1 blockchains, gas fees have always been high," he stated in a16z Crypto's podcast in April this year.

"In the past, you did need to pay a few dollars or even tens of dollars in transaction costs to qualify for an airdrop. However, as infrastructure continues to improve, the cost of operations has become very low. I believe this will fundamentally change the game dynamics of attack and defense mechanisms." Eddy Lazzarin, CTO of a16z Crypto, has been emphasizing the importance of building 'proof of human' mechanisms.

"AI can now generate a large number of realistic behavior records. The most advanced robot farms are now almost impossible to reliably identify, and it won’t be long before those with medium technology become equally undetectable," Lazzarin wrote in an article in May this year. What Lazzarin is most interested in is constructing a 'proof of personhood' mechanism: it should allow real humans to easily and freely verify their identity while imposing high costs and operational difficulties on robots or fraudsters attempting to commit large-scale fraud. He mentioned that the iris scanning project World initiated by Sam Altman is a typical example of this kind of mechanism. The core idea of this project is that everyone can only register for one World ID, with its uniqueness verified through iris scanning (since everyone's iris is unique).

Lazzarin added in the airdrop-themed podcast: 'I really hope to see more people trying systems like World ID, which combines biometric technology with privacy protection mechanisms to limit each person to a single identity ID.'

However, Ethereum co-founder Vitalik Buterin believes that 'one person, one ID' is not a perfect solution, as it means that all historical actions could be tied to a single attack point — that is, the key associated with that identity. Once leaked, the risks are immense. He also pointed out that biometric and government identity information can itself be forged.

Why not simply cancel crypto airdrops?

If crypto airdrops are so easily manipulable, the most straightforward choice seems to be to simply cancel the airdrop mechanism. However, there are also viewpoints that believe airdrops still have their significance. Airdropping tokens to users who genuinely participate in the protocol not only helps to decentralize project governance but also disperses control through mechanisms like granting voting rights. Moreover, airdrops often generate a lot of topical hype. "One obvious reason is: when you distribute a large number of potentially valuable tokens, you will attract a lot of attention, which itself has a marketing effect," Lazzarin stated. "Airdrops are essentially a marketing tool."

Wilton also agreed and pointed out that project parties should anticipate that some users will sell tokens, which is essentially the marketing cost incurred to acquire users, with the key being to ensure these users are real people and 'willing to stay long-term.' Meanwhile, Binance believes that automated robots are not entirely harmful. In fact, in certain scenarios, if used properly and transparently, robots can play a positive role — for instance, providing liquidity, executing strategies on behalf of users, or conducting stress test simulations during audits.