Editor | Baiding, Geek web3

Wu said authorized to reprint

Abstract

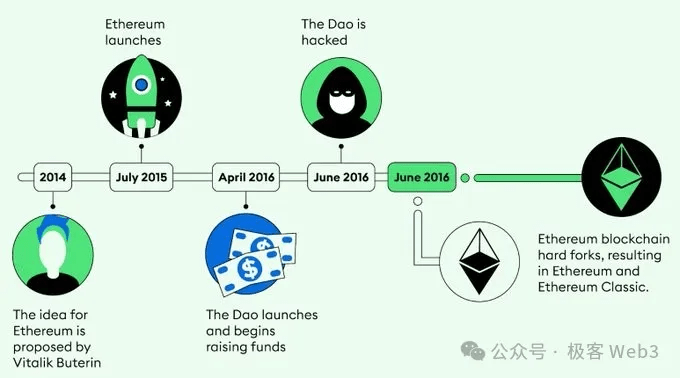

TheDAO is a smart contract project aimed at creating a decentralized autonomous investment fund, developed and deployed on Ethereum by the Slock.it team in 2016. The design vision of TheDAO is to manage funds and make voting decisions through smart contracts, thereby managing funds and projects in a self-governing manner. The project attracted a large amount of ETH investment, becoming one of the largest smart contract projects on Ethereum at that time.

However, shortly after the launch of TheDAO contract, a security vulnerability was discovered, which the hacker exploited to attack and steal a large amount of ETH. This incident caused a stir in the entire blockchain community, prompting the Ethereum community to engage in extensive discussions and voting on how to resolve this issue.

Ultimately, the Ethereum community resolved the TheDAO incident through a hard fork to recover the stolen funds and lifted the hacker's control over the funds. This incident became an important case for the blockchain community to discuss and reflect on issues such as smart contract security, decentralized governance, and community consensus.

This article is a summary of the discussion on TheDAO incident held by the podcast Forkit on December 6, 2018. The host of this episode is Daniel, and the guest is Jan. Both are co-founders of the CKB/Nervos public chain.

Both sides have sorted out the ins and outs of the TheDAO incident from the perspective of participants and conducted in-depth discussions on popular issues such as hard forks, community governance, and Code is Law, which is still worth learning for everyone today.

Text:

Danial: Let’s talk about the largest fork in Ethereum history that everyone is familiar with, namely the 'TheDAO incident'. Regarding TheDAO incident, both of us were actually participants. Jan, could you briefly recap your feelings about TheDAO incident? Before you speak, I want to briefly introduce TheDAO incident. First, there was a well-known blockchain company in Germany at that time called Slock.it.

In 2016, at that time, the environment of the blockchain industry was vastly different from now. It was very difficult for a blockchain startup to gain support from traditional capital and to raise funds because you were not a joint-stock company and could not supervise and manage your business behavior and earnings under the current legal framework and regulatory mechanisms. None of this had formed a logic or framework at that time.

At that time, although the concept of ICO already existed, it was still very early. The ICO boom occurred in mid-2017, so how did blockchain companies do early financing a year before the ICO boom? Slock.it proposed an idea to use blockchain smart contract technology to create an on-chain version of a VC, where everyone could crowdfund for this company with cryptocurrency and then invest in some projects on the blockchain, sharing the profits. This method of sharing dividends using the instant settlement capability of smart contracts is obviously a great idea.

At that time, over 15% of the circulating Ethereum in the world was invested in TheDAO contract.

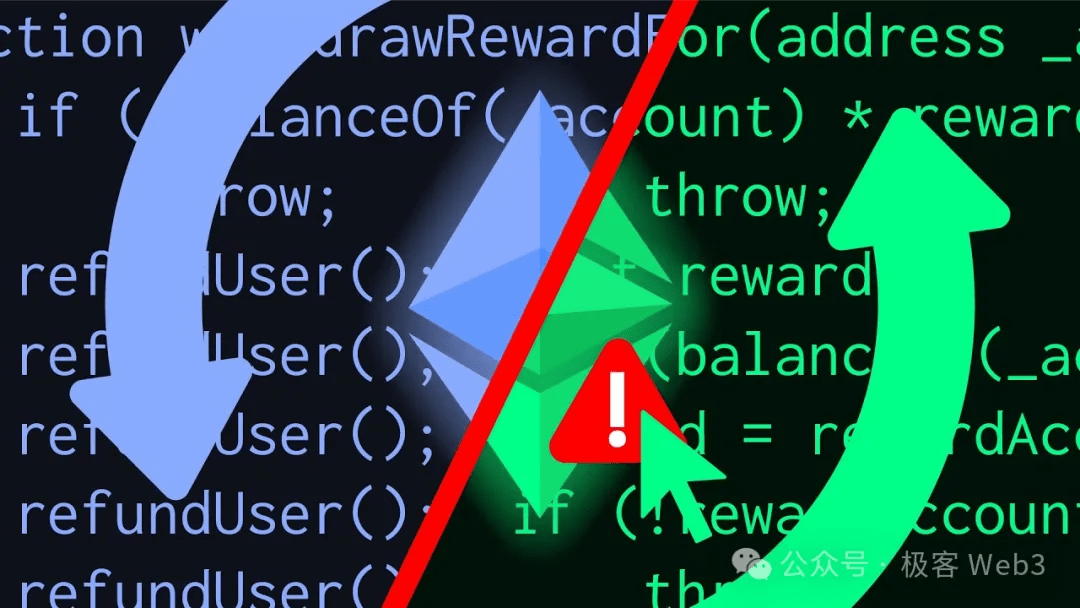

However, a bug in TheDAO contract was discovered and exploited by hackers. This bug is actually very simple. As a technical expert would say, if you look at the code, you can find a bug that can be exploited in a loop, allowing the hacker to withdraw funds from TheDAO contract an infinite number of times. For example, if the hacker could originally withdraw 10 ETH, they could repeat the withdrawal process a thousand times, and thus they could withdraw 10,000 ETH.

It was such a problem that caused over 30% of the ETH in TheDAO contract to flow into a sub-contract controlled by the hacker, although it couldn't be withdrawn immediately and had to be locked for 28 days.

At that time, the entire community was in an uproar. We were all participants in this event. That day, I remember I was in the imtoken office, still working on the development of the imtoken mobile wallet. That afternoon, there was a frozen atmosphere in the entire office because TheDAO was a project that each of us held in high regard and participated in to some extent, so everyone was particularly nervous. The core team led by Vitalik concentrated all their efforts on addressing the TheDAO hacking incident.

Vitalik made a judgment at that time and said that there were roughly three ways to solve this problem:

The first way is to surrender; those funds will be taken away by the hacker when the time comes, and then we can find a way to stop TheDAO and return all the remaining funds to the investors.

The second way is to complete a soft fork, locking the hacker's money so that he cannot take all the money away, but the soft fork only ensures that the hacker does not benefit but cannot recover the investors' losses.

The third way is to execute a hard fork after the soft fork, which could return all the money stolen by the hacker to the investors. The third way is obviously the best from an economic perspective, but the problem is that this hard fork was not for technical protocol upgrades but to address the hacking incident, and it is not 'well-grounded'.

Regarding the correctness of this fork, the entire community engaged in a very intense discussion that lasted a long time. I remember each of us participated in that discussion. Jan, do you still remember?

Jan: Yes. When the TheDAO incident happened, I remember I was walking on the road, and it seemed that Shaoping came to find me because we were working on EthFans at that time.

Danial: Yes, Shaoping was the operational head of EthFans at that time.

Jan: Yes, he told me on WeChat that it seemed TheDAO had an incident, so I went to check and quickly realized this was a serious security accident. I immediately told Shaoping to create a group to gather everyone in the community, at least those from the Chinese community, for discussion, and to facilitate further communication between the entire Chinese community and the Ethereum Foundation. Since this was a security incident, there would definitely be follow-up measures, and community communication was necessary.

At that time, we discussed how this attack happened. Because at that time, everyone only knew that something had gone wrong, but how the hacker managed to take the coins from TheDAO contract was still unknown. Everyone in the world was analyzing, but no one knew what exactly happened. In the end, it was said that the hacker discovered two vulnerabilities consecutively. The first was a proposal from SplitDAO. But that was not enough, because this vulnerability could only be exploited once, stealing only $1 million. So how could they steal all the money?

At this point, the second vulnerability, which is the most famous reuse attack vulnerability, needs to be utilized. If these two vulnerabilities are combined, the hacker can steal all the money. So the hacker actually stole a lot of money.

Danial: You might not remember the specific details of the second vulnerability, but I remember another thing, which is that you were the first in the Chinese community, I don't know if it was globally, to discover the combination of two vulnerabilities, and you immediately wrote an article about it.

After your article was published, I edited it into the community. I made a small contribution to this article by naming it 'Gul'dan's Hand'. This article is especially valuable for learning, including your complete analysis process, which is very good.

I think the TheDAO incident was particularly dramatic. Previously, we had an internal interview discussing the attack on TheDAO and how to reach community consensus for the hard fork. I played a small, relatively important role in it, inspired by an idea given to me by the founder of Bihu, Gulu, to create a voting website called CarbonVote.

Then we used this website to gather all the investors in TheDAO who still had their ETH not stolen, using the ETH they held to conduct a safe vote on whether to proceed with this hard fork.

Fortunately, the official Ethereum team saw the website I created. They believed that my idea was operable, and ultimately, they used this website as the main voting site to decide whether to go for a hard fork. This was an interesting experience for me to deeply participate in this event.

Jan: Yes, I think this was a meaningful thing done by the Ethereum community in China at that time. I remember that Gulu and Vitalik discussed this CarbonVote a lot, and in the end, you personally implemented it. Indeed, the entire community was watching this because, in the end, the Ethereum Foundation said there was a voting website, and if anyone had any opinions, we could vote to try it out.

I think this is very meaningful because it actually reveals many problems; one is that many people came to vote, and you can see a rough opinion of the community, but it also highlights a very obvious problem with voting on the blockchain, or you could even say blockchain governance — too few people participated in the voting.

Danial: Now I want to express two feelings I have after TheDAO incident. The first feeling is that before TheDAO incident, we did blockchain development, whether at the base or the application level, we lacked that 'sense of security'. Before TheDAO incident, we did not have a sense of security, but after TheDAO, we all placed security in a crucial position.

We know that every step can produce irreversible losses, and we must place security in a very important position, always maintaining a sense of security. This is the biggest change everyone has made in blockchain technology development before and after the TheDAO incident. Before TheDAO, we did not truly value security; after TheDAO, we realized how important security is.

Jan: That's right. I think before the TheDAO incident, programmers writing smart contracts probably thought: it's just a program. It was only after TheDAO that they realized: we are now writing smart contracts that hold money!

This is actually very educational. You can also think of the occurrence of TheDAO incident as inevitable because even if the funds stolen were not from TheDAO contract, there would definitely be another ADAO or BDAO emerging, as people's security awareness had not kept pace. Therefore, it is necessary to establish security awareness through such bloody lessons. Although it is regrettable, countless security incidents still occurred after TheDAO incident.

I remember that after TheDAO incident, the Devcon2 held in Shanghai had an abundance of talks about formal verification and smart contract security, and the community's attention to security was very high.

I remember there was an interesting thing, which should have been before the TheDAO incident. I said in a group that smart contracts really need formal verification. But at that time, everyone was very pessimistic about the prospects of formal verification. Some people who were studying formal verification said in the group that it seemed that there were very few places where formal verification could be used, and many things could not be done. It might take a long time before formal verification could combine with smart contracts or be widely applied.

But it's interesting that just half a year later, research on formal verification was flourishing, and many people working on formal verification immediately entered this field. Just as blockchain brought many cryptographers into this field, the TheDAO incident brought many formal (verification) researchers into Crypto. From this perspective, the TheDAO incident was very significant for academic research.

Danial: Because after TheDAO incident, they found it easier to obtain resources to support their research on this path, which would lead to better progress. I feel that every so often, interesting new things will emerge in the field of formal verification. This is the greatest significance that the TheDAO incident brought us from the perspective of security.

Another thing I want to mention is 'difficulty'; this difficulty refers to how hard it is to reach a consensus. At that time, everyone was already a victim, with 15% of such a large number of tokens locked. In a situation of widespread grief, it was still very hard to reach a consensus for a hard fork. Even in the end, even if we thought we had reached a consensus through the voting website, there wasn't really much controversy.

I can tell you that after the voting, everyone knows that the TheDAO incident ultimately decided to go for a hard fork, but there was a long debate before the hard fork. Everyone was very rational, but both sides held their ground, as this matter involved the 'Code is Law' principle, which raises metaphysical discussions about whether the dispute lies in the outcome or the process, making it inherently difficult to reach a final consensus.

In normal circumstances, we change the state by initiating transactions. For example, if I spend two UTXOs, these two UTXOs become history, and then two new UTXOs are created, which are the new state. Thus, the current state changes accordingly.

In the end, Ethereum completed the fork after the TheDAO incident, forming two chains, and many people still did not abandon the 'original Ethereum'.

Jan: Oh right, I actually want to ask you a question: do you think that most people who chose to support the fork indicates that most people can give up their beliefs for their interests, haha?

Danial: In fact, I think it was only a small portion of people who chose to support the fork rather than the majority. Let me explain why. At that time, the total circulating supply of ETH in the entire Ethereum was 70 million. So let me do the math for you: among the 70 million tokens, 15% were locked by TheDAO, and actually only these 15% holders were stakeholders, and I believe they were willing participants in TheDAO project, which is part of the active and leading individuals in the community.

All the tokens of these people were locked, so only the remaining people could vote on how to fork, because at that time I didn't manage to allow those who locked their tokens in TheDAO contract to participate in the voting. If I had done that, it would have been fair; they are the parties involved.

So it was actually those who had not locked their tokens that determined the fate of those locked tokens. From the voting rate of the unlocked tokens, the total number of participants was actually very small. I don't remember the exact number, but it felt like it was around a million. So only a small portion of people participated in the voting, and most of these people supported the fork, which ultimately led to such a hard fork decision.

You just asked me if everyone is willing to choose interests or not. I can only say that even though this incident caused quite a stir, those willing to participate in political discussions or democratic decision-making are always a small portion of the crowd, not the vast majority.

Jan: I think your answer just now was very good. In fact, you just pointed out that my viewpoint is not that tenable, because the coins of the stakeholders were locked, and those participating in the voting did not have direct stakes. I think their voting was probably more for the future of Ethereum.

Danial: I think so, I believe they do. If we were to distribute some tokens to all users whose ETH was locked in TheDAO, allowing that token to also serve as a vote, then the situation would definitely be one-sided, with all participants voting in favor of the fork. However, the conditions, technology, and complexity of the project at that time did not allow me to design such a complex voting mechanism.

Jan: But actually the other side's point can be that how do you know that the people involved in TheDAO all had their coins locked? Maybe they only put in 1/10 of their coins into TheDAO, and the other 9/10 can be used for voting.

Danial: Yes, yes, that's hard to say. But in any case, the result is that the 15% of the locked tokens are removed, and among the remaining tokens, only a small portion participated in this vote.

Jan: There is another saying that this Ethereum fork obviously reflects the so-called Code is Law, which is nonsense, and it changed the unalterable nature of the blockchain. What do you think about this statement?

Danial: I feel particularly conflicted. Rationally speaking, I am willing to adhere to Code is Law; I don't want to break an iron law that is like a stamp of thought. However, from the perspective of the parties involved, I also care about my own economic losses, and to be honest, I invested a significant amount at that time.

If you ask me to speak from the perspective of the industry, I would actually be more rational and adhere to Code is Law. If I could choose again, I would be willing to defend or follow Code is Law and reconsider. Because the hardest part is not proposing a viewpoint or belief but insisting on a belief.

If we proposed Code is Law at that time but did not insist on it in the end, then any future viewpoint or belief you propose will carry less weight.

So now we can think from this perspective. I believe that even at a great cost, one should insist on certain principles, and that insistence itself is very valuable. It was just that at that time, due to some narrow economic considerations, I did not insist so much, but now I would insist.

Jan: Wow, I understand. I think this is a very interesting viewpoint. In fact, I have always had some doubts about Code is Law because it is easy for developers to understand that writing code without bugs is impossible, especially as your app grows larger.

So if we strictly adhere to Code is Law, it means that the code cannot be changed once written; in other words, it is impossible to write code without bugs the first time. This seems unattainable, right? Therefore, at least there would be some hesitation regarding this viewpoint. From another perspective, I also want to defend Ethereum; I believe that Ethereum has not broken the unalterable nature of blockchain. Why do I say this?

Although Ethereum did a hard fork in the TheDAO incident, the hard fork changed the current state and did not change history. What is the difference between the two?

We can consider that the data in blockchain is divided into two types: one is accumulated history, and the other is the current state. For Bitcoin, what is the accumulated history? It is the transaction outputs that have been spent in past transactions, right? They have already been spent and are no longer valid, but they permanently exist in the blockchain network, and the transactions containing them also permanently exist in the blockchain. This is history.

The outputs that have not been spent, i.e., UTXOs, are the current state. When you observe the blockchain, you will find that history does not change; once transactions are packaged into blocks and placed there, history remains forever. However, the current state is constantly changing.

In normal circumstances, we change the state through the initiation of transactions. For example, I will spend two UTXOs; these two UTXOs will become history, and then two new UTXOs will be created. These two new UTXOs represent the new state, and thus the current state also changes accordingly.

In the blockchain, what is unalterable is history, while the state is constantly changing. When we examine the TheDAO hard fork event from this perspective, you'll find that this hard fork is a repair of the current state, not an erasure of history.

Because history refers to the transactions sent by hackers that stole funds from TheDAO, and these transaction records will remain on the blockchain forever. This is what I consider to be the most important quality of blockchain: all that has happened will be recorded, and all future people can see it in its original form.

Danial: Your explanation makes a lot of sense, and I fully agree. It indeed changes the state. Moreover, this state was also changed through community consensus, rather than being arbitrarily altered.

Jan: Indeed, this hard fork is very different from so-called 'arbitrary alteration' because the entire consensus process of the community took a great deal of effort. You could even see it as a human-powered PoW.

Danial: But your question to me — whether some people would choose to fork or not fork for their own interests? I think the events after the fork actually give you an answer. Once the community reached a consensus and completed the ETH fork, an exception quickly emerged.

About two days later, an exchange officially announced that they believed both forks had their own significance, so they decided to maintain the old chain (ETC). And do you know what happened next? The exchange stipulated that if users supported this decision, they could receive an equivalent amount of ETC based on the current ETH held in the exchange, meaning one amount of money could become two, driven by interest, ETC immediately surged, and even sparked a new broad discussion in the community:

Should ETH still be called ETH? Or should ETC be the real ETH, as it is the original chain? In other words, driven by interests, users in the exchange tend to recognize the original chain that would give out tokens.

Jan: Yes, but this way, I actually said something wrong earlier. People only realized for the first time that one amount of money could become two during TheDAO incident, not during BCH.

Danial: Yes, TheDAO actually happened before BCH.

Jan: Yes, yes, that’s right, but I think this is not entirely driven by interests. Because this indeed involves the issue of 'who do you think is right'. If you really think ETC is right, then you might naturally do this. Of course, there were also many conspiracy theories at that time, such as saying that the TheDAO incident or the ETC incident was instigated by this exchange, but this is unverifiable.

Danial: This might also confirm what I asked you earlier about the meaning of the fork. You mentioned that in the blockchain world, the vast majority of people agree on a direction, for example, moving to the right, while a small portion do not agree and still retain the right to move to the left.

Jan: That's right.

Danial: So users can still stick to the original path. We don't discuss motives; we only discuss possibilities. Blockchain always leaves possibilities for its users. As long as users are willing, there is always such a possibility existing, which can eliminate the idea of 'tyranny of the majority.' Does the minority have to obey the majority? Not necessarily. You can choose not to obey; just fork. And perhaps, the outcome of this fork will ultimately lead to a completely different path.

Strictly speaking, each of us is also a beneficiary of ETC because ETC indeed gave us an extra amount of money, haha. It is also difficult to say that ETC's development has reached a conclusion. However, overall, the entire Ethereum ecosystem is still concentrated on ETH after the fork, including Vitalik's core team, the foundation, and all the tools and surrounding communities.

In fact, in the past year or two, I have rarely heard anything related to ETC. I only know that it still exists and seems to have received considerable support, but its development does not make me feel that it will emerge as a completely independent and very promising path.

Jan: Actually, I think ETC has been developing quite well. Even better than BCH. Because regardless of the circumstances, ETC has a community and is indeed doing some development and many other things. Moreover, when you consider that Ethereum is going to switch to PoS in the future, and ETC wants to stick to PoW, these two completely different concepts will actually attract different groups of people.

Another point is that I think Vitalik has always been very friendly to ETC, which is something I really like about the Ethereum community. In contrast, the Bitcoin community tends to be somewhat aggressive regarding such fork matters, such as using hash power to crush you. However, during the ETC fork, Vitalik was very accommodating.

I remember there were also voices in the community saying that since everyone used the same PoW algorithm, could we attack ETC? We want to conduct a 51% attack to bring down ETC. I recall that Vitalik said something indicating there was no need to do so. From that time until now, for such a long time, both Vitalik and the entire community have been quite friendly toward ETC.

Everyone thinks there are two groups of people with different views; you develop your own, and we develop ours, and both sides can still exchange technical views. We are all working on blockchain, and all are blockchains in the EVM ecosystem, and this mutual enhancement is also a good thing. I appreciate this very much.

Danial: Yes, very, very interesting. The attitude of ETH towards ETC is evident to all; there has been no active attack, nor even verbal expression of opposition, which is a very precious thing. It's hard to imagine such a thing in the Bitcoin community, haha. I won't say more about it. I believe there are many Bitcoin holders and users, so I won't express my political inclination.

Jan: Haha, I think it's all quite interesting. The Bitcoin community might be more intense in competition because Satoshi Nakamoto quit early, while the ETH side has a more core team, so it can be friendlier. This can be seen as different schools. However, I believe that in the long run, the successful L1 blockchain will definitely move towards a state without a core, including Ethereum.

Ethereum now has a foundation and Vitalik, which can be regarded as necessary setups for Ethereum to accelerate its development as a blockchain network in a competitive position. But in the future, if Ethereum really succeeds and does well, without needing further major changes, I think Vitalik will gradually fade out, and the foundation will too.

Danial: I particularly agree with your idea. And I think this idea must have come from a long time in this industry, going through various ideological trials and observing many phenomena, before truly realizing the essence and significance of decentralization, making it a heartfelt recognition.