U.S. import tariffs continue to rise. On Aug. 1, levies will go into effect on more than 20 countries plus the European Union unless they agree on deals. On July 14, President Donald Trump said he would impose “secondary tariffs” of 100 percent on countries doing business with Russia if it does not reach a peace agreement with Ukraine within 50 days. Such threats should be taken with a grain of salt: Trump has a habit of backtracking when markets get turbulent. But the trend is clear. America’s average effective tariff rate has already risen to 17 percent, from 2.5 percent last year.

U.S. import tariffs continue to rise. On Aug. 1, levies will go into effect on more than 20 countries plus the European Union unless they agree on deals. On July 14, President Donald Trump said he would impose “secondary tariffs” of 100 percent on countries doing business with Russia if it does not reach a peace agreement with Ukraine within 50 days. Such threats should be taken with a grain of salt: Trump has a habit of backtracking when markets get turbulent. But the trend is clear. America’s average effective tariff rate has already risen to 17 percent, from 2.5 percent last year.

Objectives of tariff policy.

Among the evils Trump hopes to correct with his fees — from the Russia-Ukraine war to the witch hunt against Jair Bolsonaro, the former president of Brazil — one rises above the rest. In the president’s view, other countries exploit America by continually selling Americans more than they buy from them. Some run trade surpluses, Trump thinks, by manipulating their currencies to make exports artificially cheap. Six months into his return to the White House, how successful has he been in curbing this foul play?

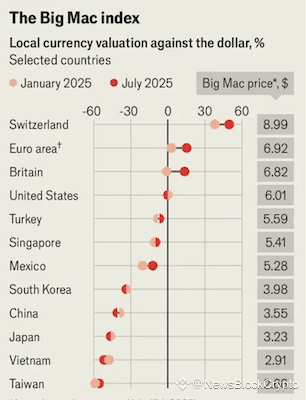

This may be too big a question to answer by studying burgers. But let’s try. For nearly four decades, The Economist has been calculating the Big Mac index: using prices of the eponymous delicacy around the world, the paper creates a quick, if rough, indication of exchange rate distortions.

Purchasing Power Theory.

The theory is that currencies should have “purchasing power parity,” meaning that their exchange rates should adjust so that the cost of the same thing in different currencies is the same.

Comparing Big Mac prices is handy because the burger is essentially the same in every country (notable exceptions include Israel, where it’s served without cheese, and India, where the Maharaja Mac is made with chicken). Purchasing power parity suggests that if a Taiwanese Big Mac costs NT$78 and a U.S. Big Mac costs $6.01, the exchange rate should be a ratio of the two prices. That means $1 should be worth NT$13. In reality, it’s worth NT$29. So the Taiwanese dollar is significantly undervalued against the U.S. dollar, according to the Big Mac Index—by about 56%.

The Global Picture of Currency Undervaluation.

Few currencies are as undervalued as the Taiwan dollar, although the Indian rupee (56%) and Indonesian rupiah (57%) are even more undervalued. Still, other currencies look cheap, even though the U.S. dollar has, after all, fallen more than 10% against a basket of other currencies since its peak in January, when we last updated the Big Mac index.

The trend is particularly noticeable in troubled countries that the U.S. Treasury Department monitors for potential currency manipulation, choosing them based on bilateral trade surpluses with America, broader surpluses with the world, and intervention in the foreign exchange market.

What explains the trend? Even as the dollar weakened on the foreign exchange market, the price of an American Big Mac has risen — from $5.79 in January to $6.01 today. Meanwhile, burger prices in Asian countries on the Treasury's monitoring list have remained unchanged. Their currencies can now buy more dollars than before, but those dollars buy fewer goods. In purchasing power terms, that offsets the change in exchange rates.

A Lesson for Trump.

There’s a parable here for Trump. His Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent had previously said the dollar would strengthen after the tariffs were imposed, offsetting the impact of higher duties on American consumers. Instead, it weakened as international investors lost some confidence in the White House’s policies.

As a result, Americans will be shocked by the double whammy of higher taxes and a weaker currency when buying imports. Hints of this are already showing up in consumer prices, which have risen 2.7% in the year through June. Americans — no matter their feelings about burgers — are feeling the squeeze as their currency loses its competitiveness.