@KITE AI For years, online identity has been treated like a single key. You hold the key, you do the thing. That model felt fine when “the thing” was you signing in, clicking around, and approving a payment you understood. Agents change the vibe. When software starts acting on your behalf, identity stops being a doorway and becomes a leash, and we care about who is holding it at every moment.

That shift is a big reason this topic is trending now. In 2025, agent tooling moved from side projects to mainstream developer work, with major platforms publishing dedicated stacks for building agents instead of treating agents as a cute wrapper around chat. Once agents can call tools, pull data, and trigger workflows, the messy question arrives: is the agent you, or is it something else that you temporarily trust?

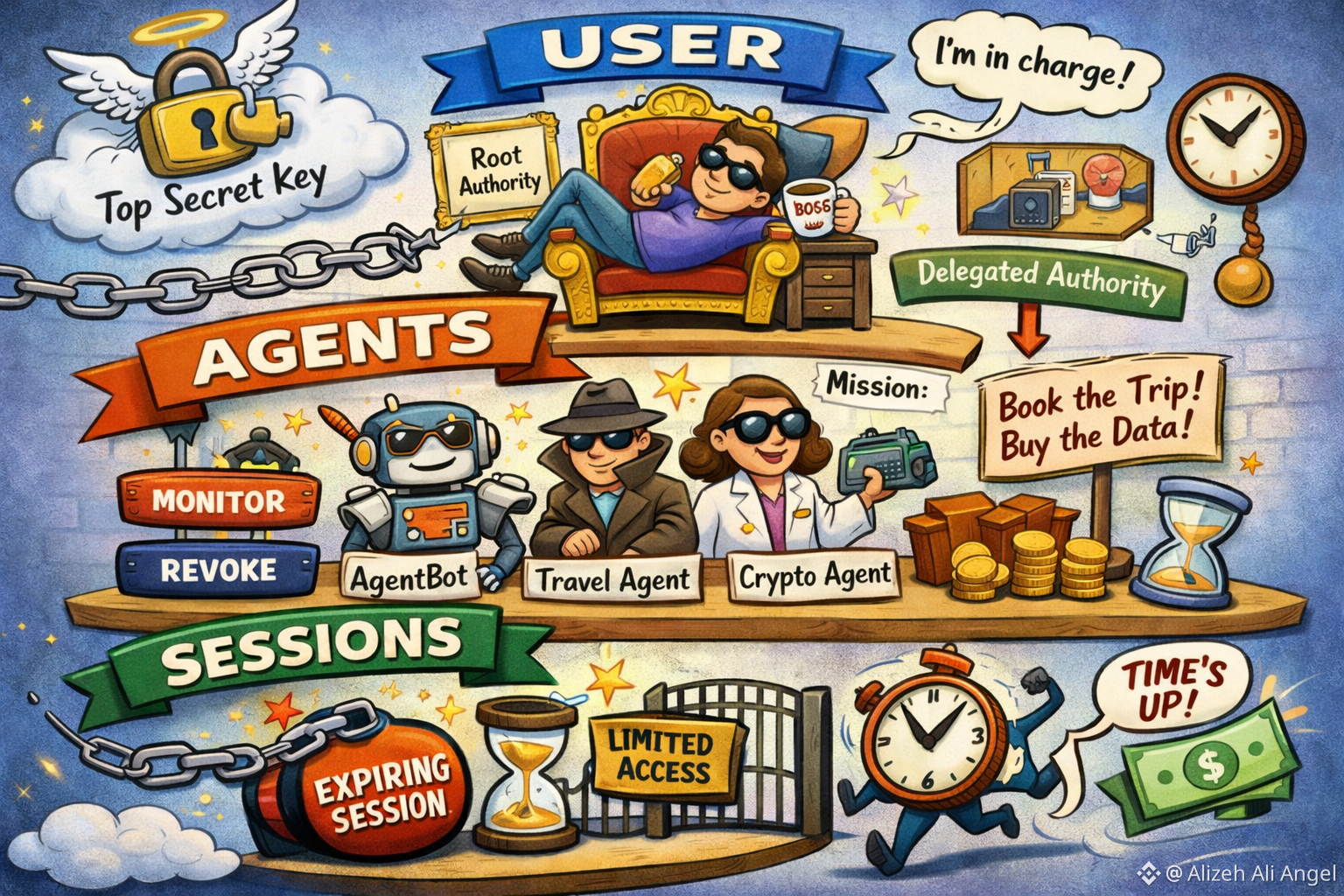

Kite, the project at gokite ai, answers with a three-layer identity model that separates Users, Agents, and Sessions. The user calls the shots. The agent is allowed to do things for the user. The session is a brief, one-time window of permission. A user is the human or organization that owns intent. An agent is a delegated actor that can take actions. A session is a short-lived envelope that limits what the agent can do right now.

Start at the top because the user layer is intentionally boring. It is the anchor you defend and the identity you do not want showing up in logs a thousand times a day. Kite’s paper says each agent receives its own deterministic address derived from the user’s wallet using BIP-32. You can ignore the math and still get the point: the agent is linked to you without being you. That distinction encourages a simple habit: keep your highest-power credential quiet, then do routine work through agents you can name, monitor, and revoke.

The agent layer is where systems get uncomfortable, because it forces you to admit that delegation is not impersonation. If an agent can do things, it should have a name, a track record, and a boundary. I like this framing because it matches how people actually operate. You might trust a colleague to book travel, but you would not hand them your passport and bank login forever. A durable agent identity lets you assign responsibilities and later say, honestly, “that was the agent, under my authority,” without pretending the agent is you.

Those limits are where sessions matter. Kite describes session keys as random and short-lived, and says sessions are authorized by their parent agent through signatures, forming a clear chain from user to agent to session. In everyday terms, sessions let you grant power that expires by default. If something looks off, you can cut the session without burning down everything: not the user identity, and not necessarily the agent’s long-term standing.

This “expire by default” idea has become a bigger theme across agent security. Security teams have warned that autonomous agents expand the attack surface through token theft, identity spoofing, and prompt injection that nudges agents into unsafe actions. The uncomfortable part is speed. A bad instruction can become a real API call before anyone notices. A session boundary doesn’t solve prompt injection, but it can shrink the damage by narrowing permission, money, and time.

If the word “session” sounds familiar, that’s because it’s also becoming a basic unit in agent builders, even when the goal is memory rather than money. The OpenAI Agents SDK, for example, uses sessions to maintain conversation history across multiple agent runs. That’s a different definition than Kite’s permissioning session, yet the overlap is telling: developers are reaching for containers that keep scope from leaking. When autonomy rises, you start designing in lifetimes, not just in permanent credentials.

Kite’s model is also landing because payments are creeping into agent workflows. As people talk seriously about agentic commerce, stablecoins and micropayments come up as a way to pay per action or per tool use without the friction of subscriptions and invoices. The moment an agent can spend, identity becomes a liability. If an agent buys data or triggers a refund, you need a crisp story: who owned the intent, which agent acted, which session was open, and what limits were in force.

None of this is a magic shield. Layering identity adds moving parts, and moving parts can fail in surprising ways. Still, I find the model emotionally reassuring in a very untechnical sense. It treats delegation as a first-class reality instead of a workaround. Imagine an agent ordering groceries: you might allow it to spend up to a fixed amount, only at certain stores, and only for the next thirty minutes. When that window closes, the privilege should close with it. It makes rollback and blame easier when things break. That is the quiet promise inside the model: autonomy with a way back to safety.